By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

On Saturday, June 27, 1970, 30 or so hippies and self-proclaimed “hair fairies” marched down Polk Street from Aquatic Park to City Hall, where they celebrated the first anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. There were no Dykes on Bikes leading the parade. No rainbow flags lined the streets. No marching band inspired the crowd. There were no floats or corporate contingents. Not only could all the participants have fit onto the back of one flatbed truck, but they also could have been fired from their jobs simply for being LGBT.

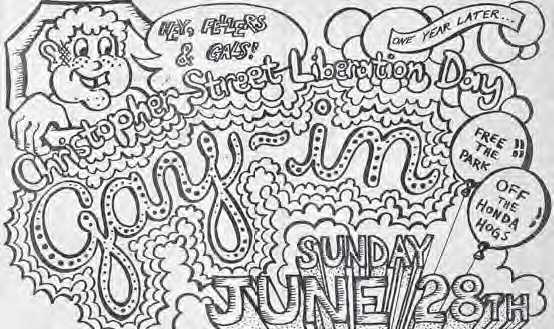

The next day some 200 revelers gathered in Golden Gate Park for the world’s first “Christopher Street Liberation Day Gay-In.” Organized by the Gay Celebration Front (GCF) and modeled after a New Left “be-in,” they had learned of the event mostly from word of mouth and a widely distributed flyer that not only informed the community about it, but also proclaimed a new vision for LGBT activism that was radically different from the one shaped by the pioneers of the lesbian and gay homophile movement less than two decades before.

Where the established homophile organizations believed in “Promoting the Integration of the Homosexual into Society” quietly through education and the “due process of law in the state legislatures,” the people who organized the Gay-In were convinced that “gay liberation,” itself a new concept, would come only through demonstrations, boycotts, rallies, marches, and direct confrontation of their oppressors. For them, the time for closets and compromises was over. It was now the time for “gay power” identity, pride, visibility, community, and the “Freakin Fag Revolution.”

Leo Laurence, one of San Francisco’s leading advocates for gay liberation, embodied and expressed the movement’s new ideas. The first step LGBTs needed to take, he argued, was to be open about themselves, to “come out” to family, friends, and co-workers to “go public” about their sexual identity and way of life. As his friend and fellow advocate Gale Whittington wrote at the time, “Liberation will come when total honesty is no longer repressed. Anything less than total honesty is slavery.”

The idea of acknowledging, never mind celebrating, their sexuality in public was unthinkable to the leadership of the most influential homophile organizations, which did not even have terms like “lesbian” or “gay” in their names. Laurence called them “timid leaders” and “uptight conservatives” who “were hurting almost every major homosexual organization on the West Coast and probably throughout the nation.” Most of them, he stated, “are their own worst enemy, afraid to become militant.” He invited them to “join the revolution” for gay rights.

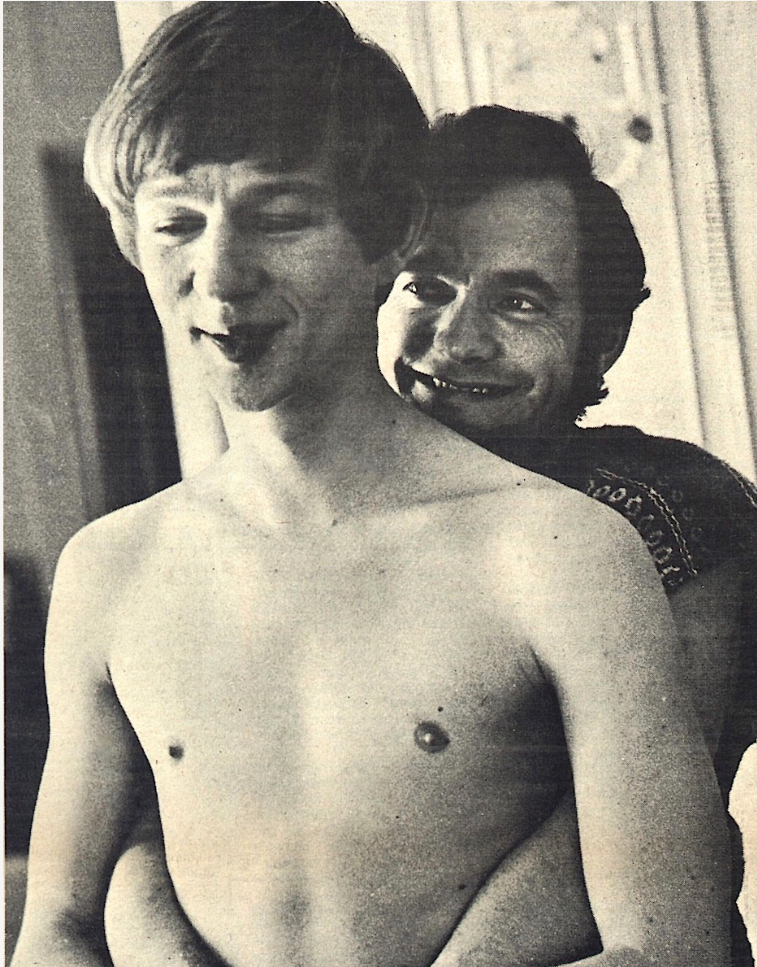

Laurence intensified both his criticism of the homophiles and his call for confrontation in an article titled “Homo Revolt: ‘Don’t Hide it’” in the March 28 issue the of the Berkeley Barb, an underground weekly newspaper begun in 1965. “Society has made us perverts for too … long,” he told an unnamed interviewer. “It’s time for a change right now.” Because the Barb included a photograph, without their knowledge or consent, of Laurence and Whittington embracing, change, at least for them, came much sooner than either had expected.

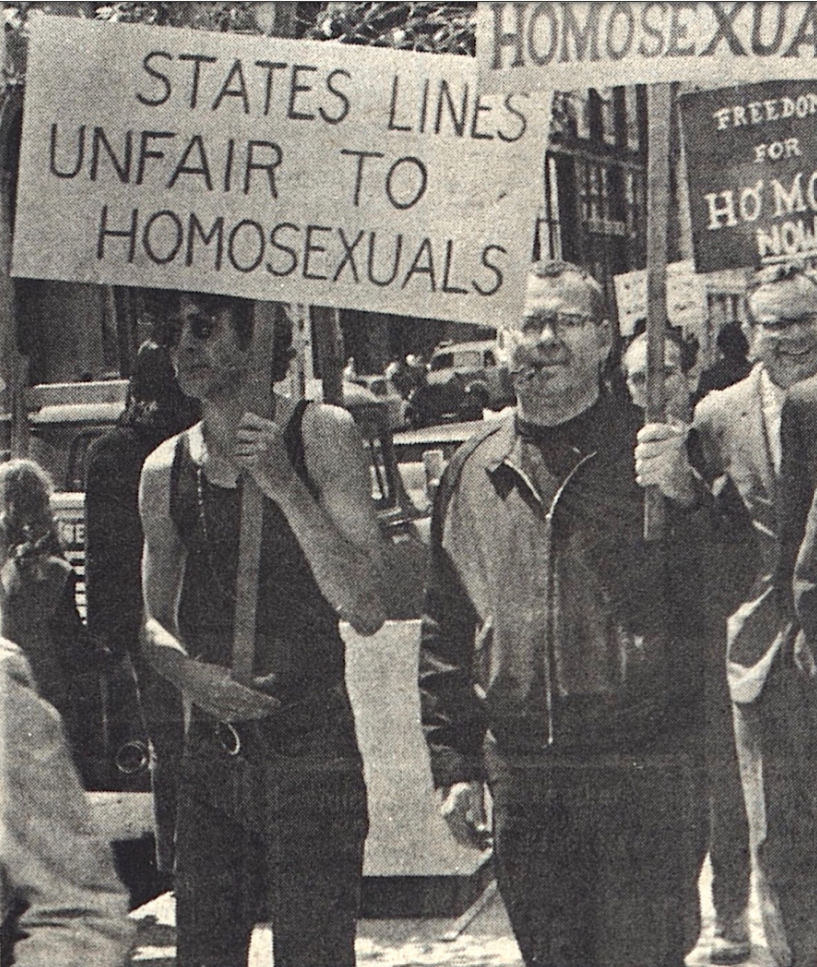

When his employers at the States Steamship Company, where he worked as a file clerk, saw the photograph, Whittington lost his job. (He did receive two weeks’ severance pay.) The next month, he and Laurence created the Committee for Homosexual Freedom (CHF)—the first gay liberation organization in San Francisco—then publicly declared their sexuality by picketing the company’s headquarters in the Financial District every weekday at noon with signs reading, “Let Gays Live,” “Free The Queers,” and “Freedom for Homos Now.” Unlike the city’s homophile leadership, the CHF embraced confrontation.

Job discrimination was only one of the issues San Francisco’s LGBT communities faced then. Police harassment was another. Only the month before the Gay-In, the city’s underground newspaper Good Times reported about the “cops [were] tearing up the grass in Golden Gate Park on bright yellow Honda Trail 90 motorcycles … where they putter out from behind the bushes and bust people for all kinds of petty daylite [sic] crimes.” In exasperation, the GCF reprinted the article about the “fruit and pot patrol, as they call it at the local station,” on the back of its flyer.

So, no one was much surprised that, while the revelers were enjoying their day in the park, the police “with military precision … force invaded the Gay Liberation Front ‘Gay-In’ at Speedway Meadows.” According to the July 3 issue of the Barb, participants were confronted by “six or eight Honda Pigs and a Jeep patrol car,” “while a mounted patrol man pranced his horse and stroked pistol[!]” They “were harassed, asked for ID, and searched.” Seven were taken into custody.

According to Laurence, the celebrants had been passing bread and wine “almost like a religious meeting” when the police arrived. “We told them we were only indulging in our constitutional right of assembly, and asked them to … join us in our love, but they wanted to hassle us instead.” He continued, “The gathering was beautiful and peaceful before the police came, the homophiles gathered in pride in their identity.”

Without knowing it, Laurence identified what the true revolution that Stonewall came to symbolize was all about. First, he believed lesbians and gays “have to love themselves.” They “have to get over this b.s. of guilt, the feeling we are degenerates” or “there will be no change.” Then, “after we can believe to ourselves ‘gay is good’ the revolution will come.” We did and it did. More than anything else, we celebrate the pride we have in our identity and in each other, publicly and proudly.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Recent Comments