By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

“He who kills a man kills a reasonable creature, but he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself.” —John Milton, Areopagitica, 1644

For hundreds of years, the guardians of other people’s minds and morality tried to make sure that “the love that dare not speak its name” did not speak at all. Authority forbade books about women loving women and men who loved men. Publishers refused to print them. Authors feared to write them. It was not only same-sex intimacy that could not be acknowledged. An entire world of individuals was made to disappear.

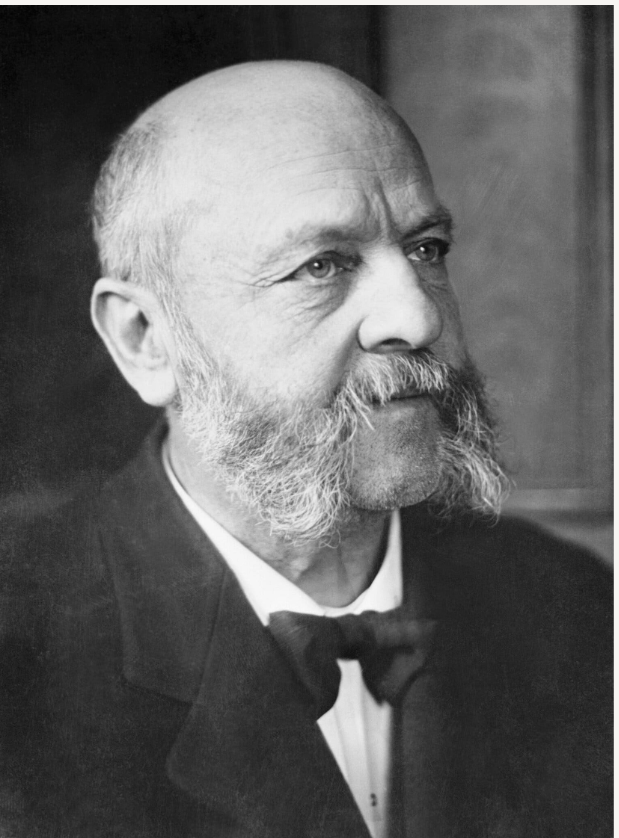

Johannes Gutenberg, who in ca. 1452 produced the first book in Europe printed from movable type on a press, probably was also the last publisher not to worry about his work being censored or banned outright by secular authority or canon law. Even with its accounts of fratricide, mass annihilation, adultery, incest, rape, betrayal, and much more, Gutenberg’s Bible was praised by both church and state; it sold out quickly.

Gutenberg’s technical achievement created an ever-expanding world of information that demanded less and less expensive books, pamphlets, broadsides, and handbills that could be read by or to more and more people. The easier and cheaper printing became, however, the easier it became to share new ideas and different views of the world, including some that might offend prevailing public attitudes and threaten the powers that be, who could do something about it.

Censoring same-sex content began early and transformed even classic texts. Before Marsilio Ficino published The Platonic Theology in Florence in 1482, his commentary on Plato’s Symposium, he completely erased the homoeroticism of the original; men no longer had a sexual attraction to each other, only a spiritual one. The first English translation of the Symposium itself, published 1761 and revised in 1804, went even further, making women, not men, the object of men’s “purest desires” and turning Plato’s male “army of lovers” into an “army of knights and ladies.”

Poor Plato. The English poet Percy Shelley, whose wife Mary wrote Frankenstein, translated the Symposium in 1818, when he was 26, but his manuscript was not published until 1840, after his widow and the essayist and critic Leigh Hunt created a blue-penciled version of it that changed “men” to “human beings”; “love” to “friendship”; “his beloved” to “the other”; and deleted any text that could be read as homoerotic. Shelly’s true text did not appear until 1931—in a private edition of one hundred copies.

Plato and Shelley were not the only great authors who were rewritten or censored to remove any sense of homosexuality. Before Michelangelo’s homoerotic love poems were published in 1623, his great nephew, who edited them, heterosexualized them by replacing the pronoun “he” with “she” as the object of affection every time it appeared. Worse, he simply did not include most of the passionate verse his famous relative wrote remembering Cecchino Bracci, his beloved student. A corrected edition of the poems did not appear until 1863.

Shakespeare’s first editor did the same thing to his sonnets in 1640; women, not men, became and remained the object of affection in the only available edition for the next 140 years, after which the “experts” denied any homoeroticism in the text for another two centuries. Even now, some scholars argue that the first 126 sonnets, devoted to Shakespeare’s “fair youth,” a “lovely boy,” cannot be about same-sex desire because there was no concept of sexual orientation or gay identity then.

At first books were censored, banned, and burned locally. By the 16th century, however nearly all of Europe’s central governments had agencies and officers to regulate, control, forbid, and confiscate what was printed. Some material about affaires de c?ur between men and women might or might not be acceptable, but authors, editors, and publishers understood they were not allowed to include any mention at all of homosexuality in their books.

The most consistent, concerted effort by government to ban books began in the mid 19th century, after the introduction of the penny press in Great Britain and the dime novel in the United States made reading matter available to almost anyone who wanted it. The first modern, secular English law against obscenity, the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, allowed for the seizure and summary disposition of all impure, vulgar, profane, and pornographic materials, even when found in private homes.

Challenged in court, the act was upheld in 1868. Now the government could ban any publication that had a “tendency … to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.” Not until 2019 did the Crown Prosecution Service indicate that it would no longer forbid even “material that is purposefully obscene” when, “in the interests of science, literature, art or learning,” it could be justified as being “in the public good.”

In the United States, Congress passed the first nationwide “Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use” in 1873, making it illegal everywhere to create, sell, mail, or own any “immoral” texts or items. Anthony Comstock, who headed the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and promoted the legislation, later boasted that he personally was responsible for 4,000 arrests and the destruction of 15 tons of books.

Authors certainly got the message. Wanting to find a publisher and an audience while also avoiding the very real possibility of going to prison—and feeling the need to protect their reputations—they used deeply coded language, spiritualized same-sex relationships, published privately, or censored themselves by changing genders. One example: the man who clung to Walt Whitman in his manuscript of “Once I Pass’d through a Populous City” became a woman in the printed version.

Sometimes authors banned their own work. Gertrude Stein wrote Q.E.D., the story of an ill-fated lesbian love triangle in 1903. Although her sexual orientation was widely known, what was possibly the first modern lesbian novel remained solely among her papers until 1950, four years after her death. E. M. Forster’s Maurice, written in 1914, did not see print until 1971, the year after he died; Forster himself believed the book was unpublishable during his lifetime.

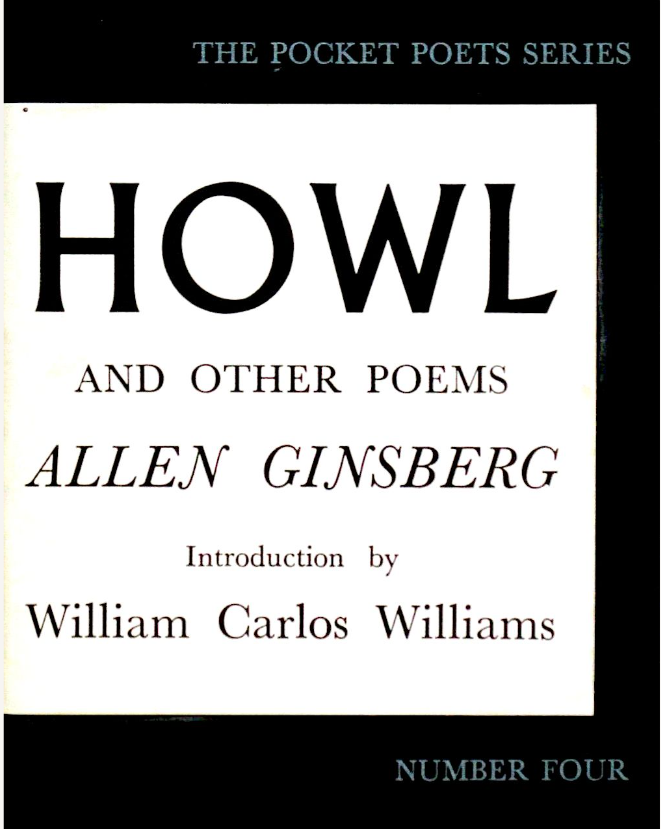

By then public sentiment and legal opinion had changed greatly. In 1957, the United States District Court in San Francisco decided that the poet Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems was not pornographic because of its “redeeming social importance.” Although the ruling applied only to California, it became a precedent for the United States Supreme Court when it established the criteria to determine if a publication can or cannot legitimately be subject to government regulation.

Ten years later, the United States District Court of Minnesota ruled that publications “were not obscene simply because they might be aimed at a homosexual audience.” The “rights of minorities expressed individually in sexual groups or otherwise must be respected.” Authors now could feel safe writing books about LGBT people and topics. Publishers could print them without fear they would be confiscated. Readers could buy them, own them, and give them as gifts without violating any laws. Until today.

The current attacks against books about LGBT people are not simply against our right to read, but against our right to proclaim our very existence; to express ourselves freely; and to live our lives openly, not hidden in the shadows. We must be always vigilant of the self-righteous moralists who want to move us backward to 1873 and especially to 1482. As famed attorney Clarence Darrow said 100 years ago, “Ignorance and fanaticism are ever busy and need feeding.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on October 5, 2023

Recent Comments