By John Lewis–

Years ago, I worked as an English teacher for refugee children from the wars in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos at a camp in the Philippines that housed refugees before their final resettlement to third countries, such as the United States.

One of the most complex and emotional moments of camp life came when it was actually time for refugees to depart the camp to begin their new lives in America and other countries. Many of us teachers would gather to wave goodbye to the students and their families as they boarded buses to transport them to Manila Airport and their futures. We also made sure we exchanged each other’s contact information so we could reconnect in the U.S.

At first, I naïvely thought that departing the camp would be a moment of pure joy for the refugees. Their harrowing journeys, many of which had begun by fleeing Vietnam on flimsy fishing boats in the dead of the night, trekking through the Killing Fields of Cambodia to safety, or traversing the Mekong River from Laos to Thailand, were finally over. Hope for a bright future lay ahead.

But for many refugees, departing the camp was bittersweet—even heart-wrenching for some. For many, the moment represented the final act in leaving behind their home countries forever. Being able to return to Vietnam, Cambodia, or Laos someday even just to visit seemed unimaginable given the countries’ oppressive regimes and very difficult living conditions after years of war. Tears streamed down many refugees’ faces as they believed this was the last moment they’d live in Southeast Asia together in community with people from their home country.

However, things changed over the decades. Beginning in the 1990s, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos started to open again to various degrees. Many things remain highly problematic, including Vietnam’s recent crackdown on peaceful dissent. But many refugees were able to do what had once seemed unthinkable: return home to visit loved ones, re-establish connections with their home countries, and, for some, even come back to live.

When the Taliban reclaimed control of Afghanistan last year after twenty years of American-led war, my experiences working with Southeast Asian refugees became meaningful to me in new ways. Vietnamese American friends explained how the images of Afghans desperately trying to flee at Kabul Airport retriggered the trauma they experienced escaping their own home country.

I also thought of the thousands of LGBTIQ Afghans now in extreme danger with the return of the Taliban and the reinstatement of Sharia law. While same-sex activity was criminalized under Afghan law during the American occupation, life for LGBTIQ Afghans is now far more precarious. A Taliban judge declared last year that “[f]or homosexuals, there can only be two punishments: either stoning, or he must stand behind a wall that will fall down on him,” according to an open letter from several major LGBTIQ rights organizations to President Biden urging him to take bolder actions to protect LGBTIQ and other particularly vulnerable Afghans.

The first 29 LGBTIQ Afghan refugees arrived in the United Kingdom last October. More followed in November with an unknown number making it to Canada in December. Upon reaching the U.K., one refugee told the BBC that he felt like “a human being for the first time” in his life, exclaiming: “I feel safe and free. This is amazing.”

But thousands of at-risk LGBTIQ people remain in Afghanistan, and the U.S. and other countries need to do more. Global attention also should not be confined to the plight of LGBTIQ Afghans. Thousands of LGBTIQ people live in fear for their lives across the globe, especially in the approximately 70 countries that criminalize homosexuality, including 10 that make it a capital offense.

Enabling LGBTIQ people to escape imminent threats of harm requires monumental effort. And sadly, even that is not enough. The anti-LGBTIQ attitudes and laws themselves must change, and the religious, cultural, political, and financial interests that support them must be subverted. Governments, businesses, and organizations that purport to support human rights must be active agents for change. No LGBTIQ person nor anyone else should have to choose between living in peace and personal freedom and their home.

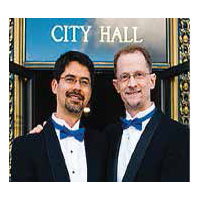

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Published on January 13, 2022

Recent Comments