By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney–

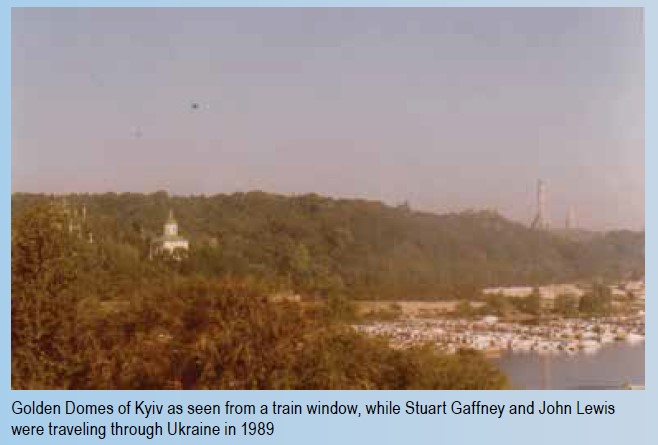

We’ll never forget gazing out our train window at the beautiful golden domes of Kyiv as we traveled through Ukraine from Moscow to Bucharest on a 1989 trip to the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Today, the Russian military at the command of President Vladimir Putin is reducing much of where we traveled in Ukraine to rubble. And untold thousands of Ukrainians have fled their country to Romania on trains travelling the same tracks we did over 30 years ago.

Countless other Ukrainians have fled by train, bus, and foot to other neighboring countries with by far the largest numbers going to Poland, followed by Hungary. Many will relocate to other parts of the European Union as well.

LGBTIQ Ukrainians, of course, make up a significant number of those refugees, and are also among the millions of Ukrainians who remain in the country to face the invading Russian military. (All Ukrainian men aged 18–60 are required to stay in the country.)

Vladimir Putin’s brutal and brazen attack on Ukraine represents first and foremost a horrific human tragedy for all people affected. Even after the fighting finishes, no one will be the same as before.

The unfolding crisis also gives us the opportunity to recognize the incredible strength and resilience of LGBTIQ Ukrainians as well as the queer community in Russia and neighboring parts of Eastern Europe. For years, our collective community has exhibited tremendous pride and resolve in the face of formidable obstacles and oppression—just as LGBTIQ Ukrainians are doing in extraordinary ways today.

The LGBTIQ Struggle in Russia

Many LGBTIQ Ukrainians greatly fear what life would be like under Russian control. Russia currently ranks 46th out of 49 European countries in the latest rankings of LGBTIQ rights by ILGA-Europe (European Region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association).

When we visited the Soviet Union, we met gay Russians outside the Bolshoi Theatre when we stumbled upon the popular Soviet-era gay hangout. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, LGBTIQ Russians were hopeful for a better future. Homosexuality, which had been illegal for decades during the Communist regime, was decriminalized in 1993.

However, progress has been dramatically reversed in recent years under the nationalist leadership of Putin. Most notably, the Russian parliament, with the support of Putin and the Russian Orthodox Church, enacted legislation in 2013 designed to chill expression of support for LGBTIQ people, stop public education, and invite hostility and violence against the queer community. Known as the “Gay Propaganda” bill, the legislation banned “promotion of nontraditional sexual relations” to minors, including equating same-sex relationships to heterosexual ones—all falsely in the name of furthering “traditional Russian values.” The bill applies to all media, including print, radio, television, and the internet.

The bill may likely have caused the postponement of the July 2017 premier of the ballet Nureyev, depicting the life of Rudolf Nureyev, one of the greatest ballet dancers of all time, who was gay and tragically died of AIDS in 1993. The ballet openly portrayed Nureyev’s homosexuality, including a sensuous dance with him and one of his lovers. When the ballet finally premiered 5 months later to a restricted audience, its director was under house arrest on what most consider trumped up charges.

Also as part of a sustained anti-LGBTIQ campaign, Russian Pride events have been prohibited. In fact, Moscow authorities in 2012 banned gay pride parades in the capital for the next 100 years. LGBTIQ websites have been blocked, and LGBTIQ individuals and groups have otherwise faced discrimination or persecution. In 2017 and 2019, Chechen authorities carried out deadly anti-gay purges.

In 2021, Russia banned same-sex marriage under its constitution. And just last month, the Russian government asked a court to shut down the Russian LGBT Network, one of the country’s most prominent gay rights organizations. The Russian court declined to do so at present, but observers fear what lies ahead for the group.

However, as true testament to the strength and resilience of the Russian LGBTIQ community, a 47 percent plurality of Russian people responded that “gays and lesbians should enjoy the same rights as other citizens” in 2019 polling reported by the Moscow Times.

The LGBTIQ Struggle in Ukraine

Like their Russian counterparts, Ukrainian LGBTIQ activists and the community at large for years have shown extraordinary fortitude in the face of formidable challenges. Ukraine itself only ranks 39th out of 49 countries, just seven positions ahead of Russia, in the latest ILGA-Europe rankings. Same-sex sexual activity was decriminalized in 1991 when Ukraine gained independence with the disbandment of the Soviet Union. However, progress toward LGBTIQ rights and public acceptance has been slow.

A 2021 UCLA Williams Institute report ranked Ukraine a dismal 142nd out of 175 countries worldwide when it comes to social acceptance of LGBTIQ people. Russia, in fact, ranked higher at 126th. Anti-LGBTIQ militants’ burning of Kyiv’s oldest movie theater during the screening of an LGBTIQ film in 2014 serves as a powerful symbol of the threat under which the LGBTIQ community has lived in Ukraine.

Nevertheless, the LGBTIQ community has made advances. LGBTIQ people can serve in the military, and Viktor Pylypenko came out publicly as the first openly gay Ukrainian soldier in 2018. In 2015, the Ukrainian parliament enacted nationwide protection against employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, as part of the country’s efforts to qualify for admission to the EU.

Indeed, the EU required Ukraine to pass the measure as a condition for gaining visa-free travel to the EU. That access has proved invaluable to Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war today.

Despite threats of violence from far-right extremists, Pride parades have taken place annually in Kyiv since 2015. The first LGBTIQ equality march was held in Odessa in 2016 and in Kharkiv in 2019, with the first Kyiv Trans March taking place last year. Just a month after President Volodymyr Zelensky took office in 2019, Kyiv held the largest Pride parade in the nation’s history. Zelensky helped ensure the safety of the event, and his office declared that “Ukraine’s Constitution states that citizens have equal constitutional rights and freedoms.” Indeed, the existence of Ukrainian democratic institutions provides hope for future progress so long as the Ukrainians prevail in the conflict.

LGBTIQ Refugees and LGBTIQ Ukrainians Fighting Back

As Ukrainian LGBTIQ refugees flee the war to elsewhere in Europe, they will first arrive in Eastern European countries whose governments themselves have been hostile to LGBTIQ people and where the queer community and its supporters have shown equally inspiring strength in the face of adversity. Poland, the county receiving the most refugees, is itself at a crossroads when it comes to LGBTIQ rights. Far-right Polish President Andrzej Duda has conducted virulently anti-gay political campaigns, vilifying LGBTIQ people for his own political gain.

LGBTIQ Ukrainian refugees coming to Poland face the indignity of traveling through so-called “LGBT-free” zones that permit the banning of LGBTIQ rights marches and other events and encompass fully one third of the country. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán of Hungary, the nation receiving the second most Ukrainian refugees, is also an authoritarian leader who foments homophobia for his political gain, linking it to nationalist values and inspiring further hatred.

The Polish and Hungarian queer communities are already reaching out to arriving Ukrainian LGBTIQ refugees. Viktória Radványi, communications director for Budapest Pride, told NPR that LGBTQ Hungarians “have been giving anything they can to help—a spare room, a couch” and offering emotional support as well. Julia Maciocha of Warsaw Pride reported that the Polish queer community has been working to make sure that refugees are “placed with people who understand their needs” and to “welcome them and help them” before they likely relocate to more hospitable parts of Europe.

And LGBTIQ Ukrainians who have remained in the country appear defiant. Pylypenko reported to the Israel Hayem newspaper that a group of AWOL Russian soldiers unknowingly hid in a basement used by the Kharkiv queer community, and upon their being found, LGBTIQ community members beat and captured the soldiers. Pylypenko proclaimed that he and his queer comrades were fighting not just as Ukrainians, but also “as LGBTQ people” who “are confronting a tyrannical, homophobic enemy.”

Further, the Daily Beast reported that Veronika Limina of the Lviv queer community “has been running a camp, teaching volunteer LGBTQ cadets basic combat and paramedic skills.” Limina articulated how high she believes the stakes to be: “Either we defend our country, and it will become a part of the free world, or there will not be any freedom for us and will not be Ukraine at all.”

When we traveled through Ukraine in 1989, we could not have foreseen the tremendous changes that were about to occur there, and today no one knows what lies ahead. Perhaps Putin’s invasion of Ukraine will mark a moment of truth not just for Europe and the world, but also for LGBTIQ rights and dignity as well. We know that, regardless of what happens in the coming days, LGBTIQ Ukrainians and queer people around the world will never give up fighting for our lives.

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Published on March 10, 2022

Recent Comments