By Dr. Bill Lipsky

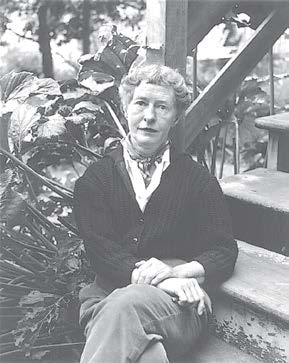

Across her long creative career, Madeline Gleason was a motivating influence and major champion of new poets and poetry of the Bay Area. By the time her own first book, titled simply Poems, was published in 1944, she was deeply enfolded in the local literary potpourri.

Gleason was especially close to the poet Robert Duncan. The same year Gleason published Poems, his his essay, “The Homosexual in Society,” appeared in Dwight Macdonald’s journal Politics. During an era when homosexuality was diagnosed as a mental disorder, Duncan argued simply that “a man’s sexuality is a natural factor in a biological economy larger and deeper than his own human will.” A pioneering and still fundamental document of gay liberation, it influenced gay and lesbian rights groups from the Homophile ’50s until the activist ’70s and ’80s.

Duncan had studied at the University of California, Berkeley, during the 1930s, but dropped out in 1938. He returned to the campus in 1945, where he met Jack Spicer and Robin Blaser, two aspiring gay poets. The three men shared so many avant-garde ideas about what poetry should be that they became a new literary movement, soon known as the Berkeley Renaissance.

Gleason was an avid supporter of the Berkeley Renaissance poets—and many other local poets. To present them to a wider audience, she organized San Francisco’s Festival of Modern Poetry in 1947, the first public celebration of poetry in the United States. Over two evenings at the Lucien Labaudt Gallery on Gough Street, twelve Bay Area poets read from their work, sometimes accompanied by music. For many of the participants, it was their first important recognition.

Because of Gleason’s festival, San Francisco acquired a reputation as a major center of modern, experimental American poetry. In addition to Spicer, Blaser and Duncan, of course, Muriel Rukeyser, not yet out, was there, as well as James Broughton, who later became a member of the Radical Faeries and then Sister Sermonetta of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

The Festival was a tremendous success. Not only aspiring poets, but also painters, authors and playwrights from all over the country began moving to the city. The Berkeley Renaissance metamorphosed into the broader San Francisco Renaissance and then the Beat Generation of the 1950s.

None was ever a single aesthetic or literary movement. They were loose associations of overlapping creative communities, made up of innovating minds who came to San Francisco looking for, and writing about, bohemian life in a world that was becoming increasingly conventional, conformist, and intellectually repressive. The LGBT poets, however, often wrote of their loves and lives, ideals and realities denied and rejected by the mainstream culture.

Gleason continued to be influential within each new movement, however. In 1952 Duncan, the artist Jess Collins—his loving and creative partner for 37 years—and the painter Harry Jacobus opened the King Ubu Gallery for alternative art in what had been an auto repair shop on Fillmore Street in San Francisco. Two years later Spicer took over the space, renaming it the Six Gallery.

In 1955 five young poets, including Allen Ginsberg, until then mostly unknown beyond a close community of friends and writers, gathered at the Six Gallery to present selections from their latest works, some still in progress. The evening was transformational.

In 1955 five young poets, including Allen Ginsberg, until then mostly unknown beyond a close community of friends and writers, gathered at the Six Gallery to present selections from their latest works, some still in progress. The evening was transformational.

Ginsberg read “Howl,” considered by many to be the greatest poem of his generation, one of the most important poems of the 20th century. Hugely influential and highly controversial, it confirmed to the world that San Francisco, always “an oasis of civilization in the California desert,” was a true and vital center of counterculture originality.

Gleason’s efforts to support and promote new poetry and its new ideas were confirmed with The New American Poetry 1945–1960, edited by Donald Allen. The first—now classic—anthology to include San Francisco Renaissance and Beat poets, it contained many of those Gleason championed: Blaser, Duncan, Spicer, Ginsberg and Broughton. Her work also was there, one of only four women chosen.

In the late 1960s, Gleason and Mary Geer, who would be her life partner for more than 25 years, moved from North Beach to the Outer Mission. During the 1970s, she could be found on a Sunday afternoon at poetry readings at the Wild Side West, a lesbian bar in Bernal Heights. Her Collected Poems, with an introduction by Duncan, was published in 1999, 20 years after her death.

Making poetry so prominently and publicly the center of their lives, Gleason and her colleagues guided tremendous attention to their chosen art. They truly took poetry out of the ivory towers of academia and into the coffee houses—occasionally into the parks and onto the streets—making it available to anyone who wanted to listen to their words and hear their ideas. Because of her own work, and her work on behalf of poetry and the poets of San Francisco, Gleason remains a principal figure in the poetry of modern America.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Recent Comments