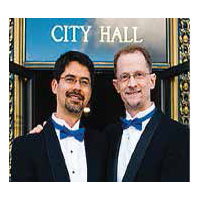

By Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis–

By Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis–

Two weeks ago, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued a path-breaking decision in favor of marriage equality and an individual’s right to self-determination of one’s gender identity under the law. LGBTIQ activists across the Americas were thrilled by the decision. Although the decision could ultimately bring full marriage equality to 19 additional countries throughout the Americas, if you were like us, you may have been a bit confused as to the decision’s exact meaning and impact and even as to what the Inter-American Court of Human Rights is.

In 1979, the Organization of American States (OAS), itself founded in 1948 to promote security and cooperation amongst the nations of the Americas, established the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to interpret and enforce the American Convention on Human Rights, which came into force in 1978. The Convention obliges all countries that ratified it to conform their domestic laws to its provisions, which guarantee essential human rights. The Court issues both adjudicatory decision and advisory opinions, in which signatory countries seek an interpretation as to how the Convention applies to particular legal issues in their countries. The Court has jurisdiction over the 23 Latin American and Caribbean countries that are currently active parties to the Convention. (Neither the United States nor Canada, for a variety of reasons, are parties to the Convention.)

In 2016, Costa Rica asked the Court for an advisory opinion as to how the Human Rights Convention applied to two issues: 1) determination of gender identity on government identification documents and 2) the economic rights of same-sex couples. And this month, the Court issued a sweeping opinion strongly in favor of LGBTIQ rights and freedom. The Court reiterated the Human Rights Convention’s protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity and that debate about these issues within member countries did not permit the countries to perpetuate historical and structural discrimination against LGBTIQ people.

With respect to gender identity, the Court recognized that a person’s gender identity was an individual and internal experience that may not coincide with gender assigned at birth and that a person’s right to self-determination of their gender identity was essential to a person’s freedom and their right to give meaning to their existence. Respect for each person’s gender identity was critical to their access to health, education, employment, and housing and their ability to live free from violence, torture and other ill-treatment. Accordingly, the Court ruled that identity documents must reflect a person’s self-perceived gender identity, that governments could not require such things as surgery or medical certification of gender change as a prerequisite to changing documents, and that procedures for changing gender identity must be simple, confidential, and efficient.

The Court was equally unequivocal when it came to marriage equality. The Court recognized that same-sex couples may form a family bond just as heterosexual couples do, and that the Human Rights Convention did not prescribe any particular form of family. The Court opined that only the freedom to marry provided equality, and that lesser alternatives such as civil unions carried a stigma of inferiority, and thus were unlawful discrimination.

Addressing religious opposition to marriage equality, the Court articulated how—as the Convention proscribes—in democratic societies, religious and secular spheres must co-exist peacefully without one imposing itself on the other, and how religion cannot be used to perpetrate discrimination based on sexual orientation. Just as self-determination of a person’s gender identity is central to their humanity, the freedom of a person to choose with whom they form a marital bond is intrinsic to deeply intimate aspects of their life and to their essential human dignity. Far from devaluing the institution of marriage, providing equal rights and protections in marriage, regardless of sexual orientation, confers human dignity on people who had faced historic oppression and discrimination.

The Court made clear that the Convention binds all countries that are party to the Human Rights Convention to follow the Court’s decision both in their legislatures and courts. Four such countries (Argentina, Brazil, Columbia, and Uruguay) and parts of Mexico already have marriage equality. The decision is thus particularly critical to attaining full marriage equality throughout Mexico and in 18 other Latin American and Caribbean countries: Barbados, Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Grenada, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Suriname.

However, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights does not have the same ability to order signatory countries to comply with an advisory opinion the same way that the United States Supreme Court and lower federal courts had the power to ensure compliance in all 50 states and U.S. territories with the Supreme Court’s 2015 marriage equality decision. Each member nation to the Human Rights Convention must still change its laws through its own legislatures or courts. Indeed, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in its opinion recognized that governments may encounter both institutional and political difficulties in changing laws and the process may take time, while recommending that countries issue temporary decrees to implement the opinion during the process of enacting permanent laws.

Embrace of the Court’s decision by leaders of two countries, Costa Rica (who brought the issue to the Court) and Panama, was swift, although as of press time, marriages of same-sex couples had not yet begun in those or any of the other additional signatory countries, and may require legislation or court decisions. Although the landmark decision of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights did not produce full marriage equality overnight in 19 countries, the decision stands as a compelling declaration of LGBTIQ rights, a testament to the extraordinary dedication and work of thousands of LGBTIQ people and human rights advocacy organizations, and a powerful tool for these activists to make marriage equality, transgender rights, and full LGBTIQ equality a reality throughout Latin America and the Caribbean.

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Recent Comments