By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

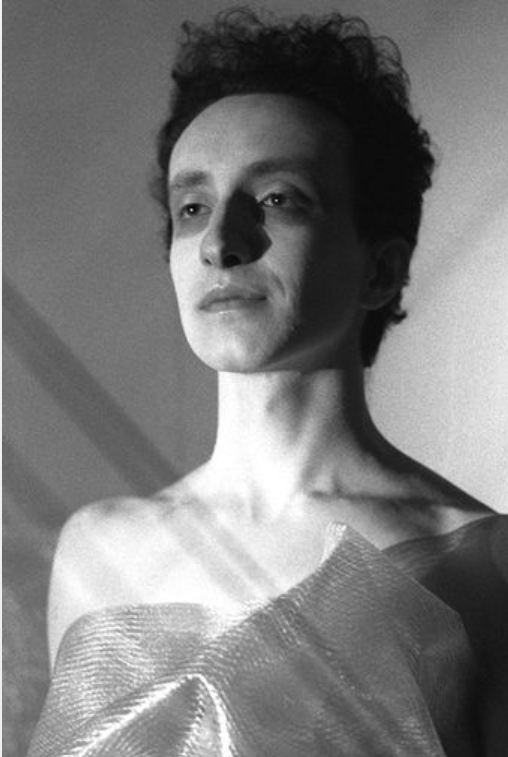

As one of the founders of Italy’s gay rights movement in the 1970s, Mario Mieli (1952–1983), knowingly or not, lived the way poet, playwright, and LGBT icon Oscar Wilde advised. “One should always be a little improbable,” he wrote in Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young. Among the most important thinkers and activists of his generation, Mieli was that and more, combining “a vision of a new sexual utopianism” with an audacious, defiant, and controversial way of life.

He was an “irreplaceable provocateur” described as “queer dynamite,” and his usually flamboyant and often shocking public behavior scandalized people both within and outside the crusade for gay liberation. His ideas, however, created a defining and hugely influential theory of queerness before he was 24 years old, when homosexuality was widely regarded as a pathology that could be “cured” with the proper “treatment.” First and foremost, “You cannot be cured of a disease that you do not have,” he told anybody who would listen. Many did.

Equally crucial, Mieli believed that “everyone is born with a complete range of erotic capability,” which meant that “homosexual desire is universal.” It was only through a process he termed “educastration,” designed “to eradicate those congenital sexual tendencies society deemed perverse,” that people “become either heterosexual or homosexual” by “repressing their homoerotic impulses in the first case, and their heterosexual ones in the second.” For him, it was “the forces that inhibit and restrict the direction of the sexual drive” that were unnatural.

Writing during a time when same-sex intimacy was illegal in much of the world and discrimination against it was widespread, even where homosexuality was not forbidden, Mieli wanted to understand why so many institutions denied LGBT people their deepest natural passions and marginalized them for their sexual behavior. His conclusion: “The hatred generated towards us within heterosexual society is caused by the repression of the homoerotic component of desire in those individuals who are apparently heterosexual.”

He simply refused to accept what he termed “the prejudices of certain reactionary rabble, i.e., all of those doctors, psychologists (whom he termed ‘psychonazis’) magistrates, politicians, priests, etc. who peddle as truth on the homosexual question the crudest lies.” Their purpose, he was convinced, was to validate and enforce the constraints against homosexuality that were “imposed by society” for its own reasons, but mostly “to encourage conformist sexual behavior based upon heterosexual marriage.”

Because Mieli insisted on “an original wholeness to all sexuality” and “the universal presence of homosexual desire,” he also disagreed with the popular belief “that the homosexual question exclusively concerns a minority,” which, for him at least, it did not. “As long as homosexuality remains repressed,” he stated, “the homosexual will be a problem concerning everyone, insofar as gay desire is present in every human being, congenitally so, even if in the majority of people it is repressed or semi-repressed.”

His solution was “the complete disinhibition of homoerotic tendencies,” which would “guarantee the attainment of a totalizing communication between human beings, independent of their sex.” The “liberation of gay desire among all,” he believed, would eventually create a sexual utopia where “the enforcement of the heterosexual norm through the removal of other components on the erotic spectrum is regarded as deeply oppressive of human nature.” Only an understanding of homosexuality as “an intrinsic part of the human being … can guide us to full sexual freedom.”

Ultimately, this would lead “not only to the negation of heterosexuality as a heterosexual norm, but also to the transformation of homosexuality, which today is still in large part subject to the dictatorship of this norm. The antithesis of heterosexuality and homosexuality will be overcome in this way, and substituted by a transsexual synthesis; no longer will there be hetero- and homosexuals, but polysexual, transsexual human beings; better, instead of hetero- and homosexuals there will be human beings. The species will have (re)found itself.”

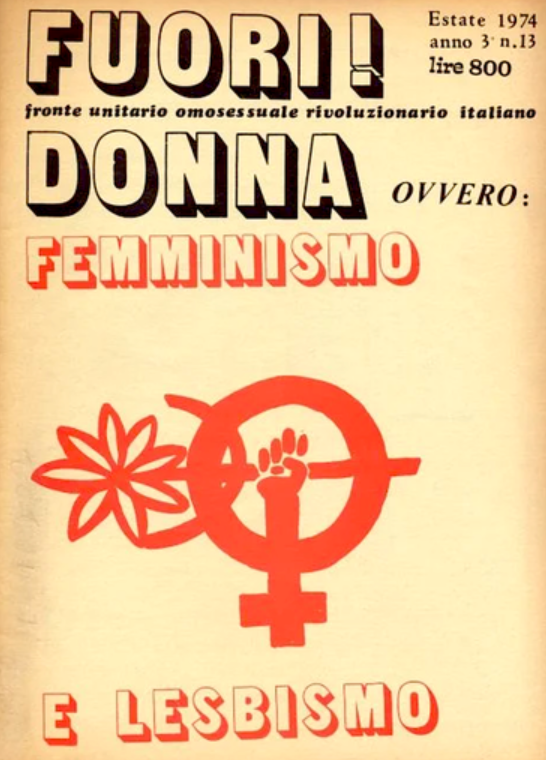

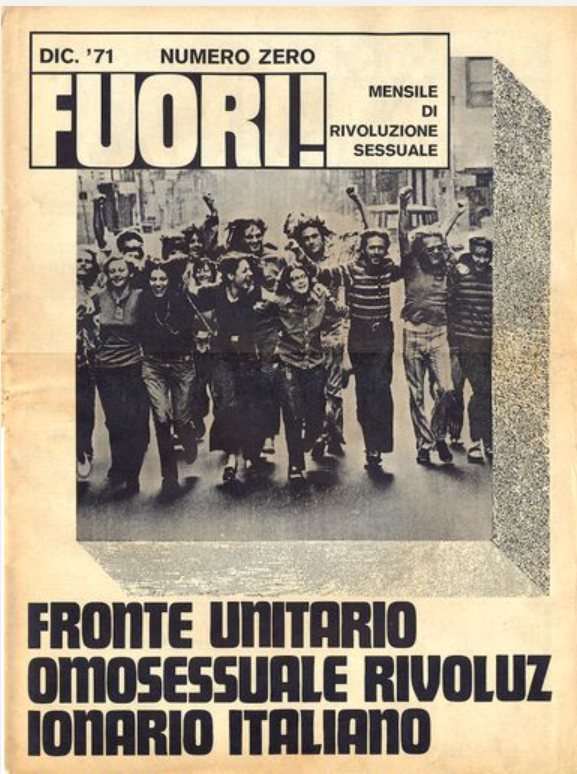

In 1972, Mieli helped to create the Milan chapter of FUORI! (an acronym for Fronte Unitario Omosessuale Rivoluzionario Italiano that also means “OUT!” in Italian), founded the year before in Turin by Angelo Pezzana (1940–). Soon after, joined by French writer and feminist Franc?oise d’Eaubonne (1920–2005), he led Italy’s first demonstration for gay rights at the Congress of Sexology in San Remo, where they protested against using aversion therapy to “convert” homosexuals. (In 1979 Pezzana became the first openly LGBT person elected to public office in Italy.) Convinced that the gay liberation movement should be independent of all political organizations, Mieli left FUORI! in 1974 when it became part of the Radical Party.

He then helped to organize the Collettivi Omosessuali Milanesi (Milanese Homosexual Collective), whose all-male theatrical group Nostra Signora dei Fiori (Our Lady of Flowers) performed his intentionally provocative and very popular play La Traviata Norma for the first time in 1976. On stage, “diversity made fun of normality and repression decided to manifest itself as a living force that contagiously incites transgression.”

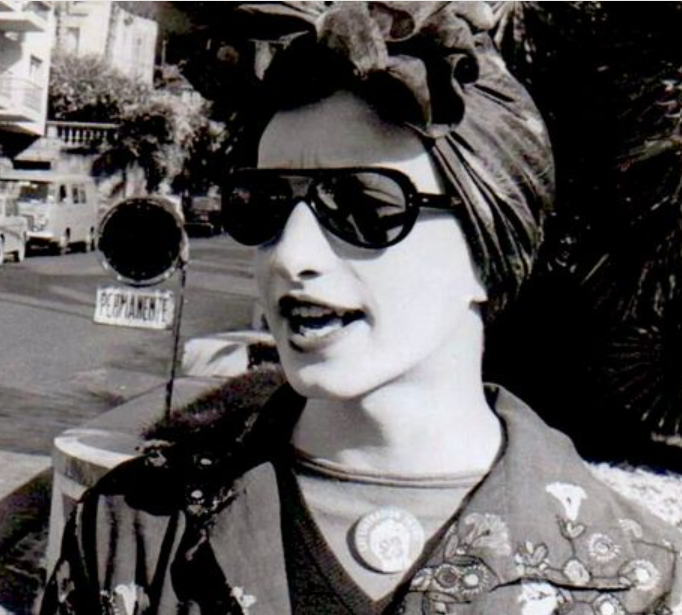

Partly because of his activism, partly because of his flamboyance, Mieli became a leading figure in Italy’s growing debate about homosexuality and sexual expression. He often appeared in public wearing a simple string of pearls and “the clothes of a lady of good family.” Always provocative, he once interviewed workers leaving an Alfa Romeo factory in full make-up, overalls, and stiletto heels. “Try to live with a clear conscience,” he wrote, “an existence that the regular mass, in its idiotic blindness, despises and tries to suffocate.”

Mieli’s pioneering blueprint for gay liberation was based upon a concept that has mostly disappeared from contemporary queer theory and politics: the foundational significance of sex. “The liberation of Eros,” he stated, “and the emancipation of the human race pass necessarily—and this is a gay necessity—through the liberation of homoeroticism, which includes an end to the persecution of manifest homosexuals and the concrete expression of the homoerotic component of desire on the part of all human beings. Baisé soit qui mal y pense. (To hell with anyone who thinks this is wrong.)”

The words of Mario Mieli are taken from Homosexuality and Liberation: Elements of a Gay Critique, published in English in 1977, and Toward a Gay Communism, a revised and greatly expanded edition of the work that appeared in 2018.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces From Out LGBT Past

Published on September 19, 2024

Recent Comments