Memories of Dennis Peron (1945–2018), LGBT Activist and the ‘Father of Medical Marijuana’

Well known as a determined medical and recreational marijuana activist for decades, Dennis Peron was also a gay activist, a civil rights activist, and a patron of the arts.

I first met Dennis after he had left the U.S. Air Force, and had moved into a Haight Ashbury commune where my boyfriend Monte also lived. Dennis was ecstatic to meet an openly gay couple who did not hesitate to hold hands on the street and kiss in theaters and restaurants. This was risky behavior in 1969, even in the Haight, and we appreciated being joined by Dennis and our friends on outings.

Dennis invited us to a Haight Ashbury party, and we noticed an intense man playing a guitar and serenading some young women. We found out later that the intense man was Charles Manson, and that his “family” was also at the party. Two women coordinated the commune and a food conspiracy, and we found Dennis in the kitchen many times. We watched the women load bright green marijuana into gelatin capsules and joints. Dennis asked them many questions, which later helped him with his future restaurant and club enterprises.

We joined a crowd of over 200 counterculture Love-In celebrants in June 1970, to enjoy the first small Gay Pride party on Hippie Hill in Golden Gate Park. It was the first San Francisco event to mark the Stonewall Riots that started on June 27, 1969, in New York City, the year before. My boyfriend Monte, Dennis, and five lesbian and gay couples were in the midst of the throng on blankets and on alert for very possible harassment. Instead, young men who passed by said, “Cool!” One of the lesbians said that she thought they wanted to impress their girlfriends with their liberal attitudes.

Dennis and I met to discuss the organizing of a San Francisco Gay Liberation Front group, and he was excited to hear about women and men from the Black Panther Party appearing at a small gay meeting in Oakland, to invite us to a Panther convention in Washington, D.C., in 1970. He also enjoyed hearing about a large Berkeley Gay Liberation Front meeting that was hosted by women from the Symbionese Liberation Army. We spoke later, and Dennis said he was too busy with his business interests and romances, but that he would support gay groups, and he did.

Dennis owned a series of marijuana clubs, where he combined a welcoming presence with a quality product. He also endured a series of law enforcement raids, and he was shot in the leg in one incident. I complained that people were pressing him to sell them marijuana while we spoke at Café Flore, with him still in pain and leaning on a crutch. With a Long Island accent similar to Harvey Milk’s, he laughed and let me know that he wanted to sell them the contraband, and that he had a stash under his bed in the hospital, and made sales there.

Dennis instantly bonded with Harvey, since they shared both a similar political view and a need to help people. Dennis financed Harvey’s political campaigns, and also his successor Harry Britt’s, and many other LGBT candidates and allies’ campaigns.

The multi-floored Peron home on 17th Street was a fine TV viewing site to watch Lyndon Johnson announce that he would not run for re-election, and to see Richard Nixon take his last official helicopter ride from the White House lawn. There was pandemonium from the audiences of what Dennis called “rampaging gay hippies.” The home was a hotbed of anti-Vietnam War organizing, and anti-conservative Nixon legislation politicking, and the crowds at such special events felt like real San Francisco progressive values in action.

Dennis’ Island Restaurant was a boost to businesses near its location at 16th and Sanchez Streets, and more than 60 people were employed there. It drew a continuous stream of guests, and many also patronized the marijuana supermarket upstairs. My German relatives were astounded when they looked into the kitchen one afternoon to see that the stoned and bleary-eyed staff were naked and mixing main courses on a table. That explained our chili merged with lentil soup lunch, and coffee blended with tea.

His largest and most successful medical marijuana club was on Market Street at Van Ness Avenue, on four floors with a large elevator. It employed more than 80 diverse people. The elevator made the club accessible to disabled and ill people, and it drew many wheelchair users. They are vulnerable on streets and in parks, while seeking pain relief, and the large club had greeters helping them on every floor. That was a club feature that was highly praised, as was Free Dope Day on Thursdays.

Grateful guests fell at Dennis’ feet and kissed his hands in gratitude while waiting in that special line, and they helped him when he ran a campaign for governor as a Republican, to stir things up and to push boundaries. Gagging sounds and laughing were heard in the background while I posed him in front of an American flag, for campaign photographs.

Dennis was the center of attention at many events, even at weddings and funerals, where mostly young people gathered around him. My lover Beau and I celebrated our 8th anniversary at the Valencia Rose nightclub, and Jose Sarria performed “Madame Butterfly” on stage, a famous erotic male film star attended, and owners Hank Wilson and Ron Lanza helped serve shark dinners and the large cake that Beau brought. Dennis was the center of the overflow audience’s attention, even when Jose led the film star onto the stage to join the opera actors. Dennis was known to hand out marijuana cigarettes at events, and he even threw joints from stages, which created excitement and applause from people who agreed with his views about the legalization of marijuana.

A large encampment of tents welcomed guests at a Summer of Love anniversary near Ocean Beach, and as they walked closer to the tents, they saw huge glittering carved marijuana leaves, and Dennis waving at them. He had a grand presence with activist followers at street fairs, parades, the Rainbow Gathering, and Burning Man.

Some of Dennis’ TV appearances included his friend Jo Daly, the first lesbian police commissioner, appointed by Mayor Dianne Feinstein. Jo told multiple audiences that she lost her appetite during breast cancer treatment, and that medical marijuana had revived her interest in eating, and saved her life. Physicians and other caregivers recommended their clients to Dennis’ clubs, and his warmth and caring was on view every day. He spotted people at the club’s front doors with green skin tones, and others walking with difficulty, and he seated them and brought service providers to them.

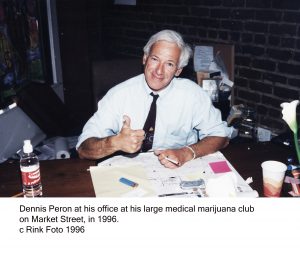

His large office at his Market Street club was a whirlwind of activity. San Francisco Bay Times journalists joined CNN and CBS news crews on couches, watching giant duffel bags and suitcases of product hauled in the door, along with a huge man wearing a horned helmet and biker gear. He carried THC-infused Rice Krispie squares, and introduced himself as a Hells Angels Motorcycle Club baker. Dennis also debated Australia’s prime minister on TV, on the pros and cons of marijuana legalization.

Dennis dedicated himself to helping people with HIV/AIDS after his lover Jonathan died. Jonathan and I discussed his condition one afternoon, while he placed morphine from an eye dropper onto his tongue to alleviate the pain of Kaposi Sarcoma in his mouth. Rainbow flag creator Gilbert Baker stopped on his way to the hot tub, listened to us, and then dropped his towel to break the tension in the room and get a laugh. Then I saw that people seated behind Jonathan, including Dennis, were crying.

Dennis sponsored my photography show at A Different Light Bookstore. The show was also sponsored by James Hormel. Mayor Willie Brown spoke at its opening and gave me a Rink Foto Day in San Francisco proclamation. Dennis asked to see it and spoke about his many awards over the years from thankful leaders in the political and art spheres.

Gilbert was a longtime friend of Dennis’ and he was given a free hand to redecorate his home, clearing away macramé, hanging bedspreads, and potted plants. It was a lavender wonderland when Gilbert was finished, and guests said that it had a new feeling of joyousness. Dennis funded Gilbert’s flag and costume creations, and his artwork. Gilbert, in turn, provided lavish decorations for many benefits hosted by Dennis, for a variety of beneficiaries. Dennis welcomed the founder of gay liberation Harry Hay and his lover John Burnside to live in the home, as refugees from Southern California. More than a dozen Radical Faeries stepped forward to serve as caregivers for the thankful couple.

My last visit to see Dennis was a Prop 215 anniversary party at his home, which is now also a B&B, and it was filled with friends of many years smoking Dennis’ dope and reminiscing about his advocacy and altruism. Dennis was in his bedroom, and he repeated, as he had said many times before, that progress had been made in furthering civil rights, women’s rights, LGBT rights, anti-war activities, and many other worthwhile causes—but that marijuana was still seen as a threat instead of a national treasure in too much of the U.S.

Please note all photos by Rink.

Rink is the legendary long-time lead photographer of the “San Francisco Bay Times.” Rink Foto on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/rinkfoto/

Recent Comments