By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

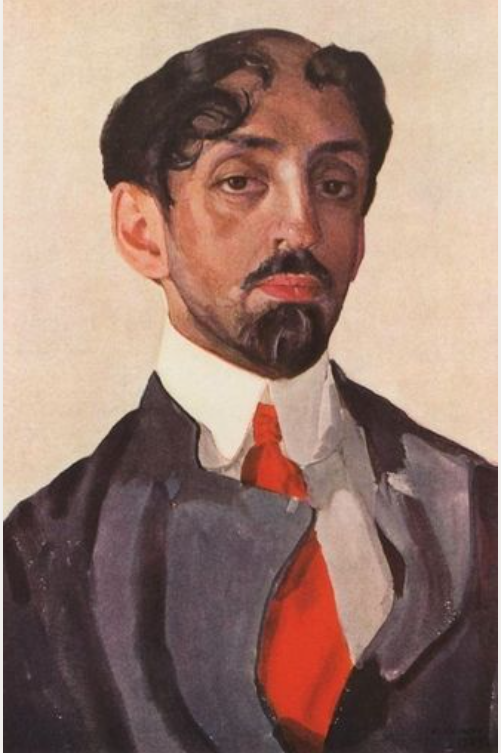

When Russian symbolist poet, author, and playwright Mikhail Alekseyevich Kuzmin (1872–1936) published his short novel Wings in 1906, it was immediately controversial. Pundits denounced it as a provocative, pornographic work, and accused its author of encouraging “sexual degeneration” with his “idealization of the sodomitic sin,” and pilloried him as “the Russian Oscar Wilde” for his sympathetic description of “the cult of male love.” No matter. Kuzmin’s affirmation of the love men have for each other made him an immediately important literary figure.

Wings was something very new for Russian literature: a coming-of-age story about a young man who discovers and embraces his true sexual self. More than a tale of physical attraction, the novel presents a hero’s deep affection for his lover as meaningful and rewarding. Equally astonishing for the era, Kuzmin’s novel did not end in abject tragedy; its characters might not have lived happily ever after, but at least they lived reasonably so. Many of the author’s readers in the generation between the 1905 and 1917 revolutions embraced Kuzmin as their mentor, model, and spokesman.

Others began writing about same-sex love as well. Five years after Wings appeared, Symbolist poet Viacheslav Ivanov (1866–1945) published Cor Ardens (Burning Heart) to great acclaim; one section, “Eros,” remembered his same-sex intimacies. His wife, Lydia Zinovieva (1866–1907), created stories about closeness between women. Nikolai Kliuev (1887–1937), leader of the New Peasant Poets, and his lover Sergei Esenin (1895–1925), later married, briefly, to dancer Isadora Duncan (1877–1927), both described their passionate relationship in their poetry.

Across his career, however, Kuzmin remained the most outspoken and certainly the most influential of Russia’s growing list of LGBT writers. Born in a small village near Yaroslavl, Russia, his family moved to St. Petersburg in 1884, where he lived for the rest of his life. At first, he studied composition, then turned to writing, encouraged by Georgy Chicherin (1872–1936), his oldest and dearest friend—they shared a lifelong passion for music, books, and men—who became the Soviet Union’s first Commissar for Foreign Affairs from 1918 to 1930.

Chicherin introduced Kuzmin to Mir iskoustva (The World of Art), a group of painters, writers, dancers, and critics who shared many of his artistic aesthetics—and also appealed to him “because of its large homosexual membership.” Guided by ballet maestro Sergei Diaghilev (1872–1929), it launched a literary journal in 1899, which became immediately scandalous for publishing an account by Symbolist poet Zinaida Gippus (1869–1945) of her visit to Taormina, Sicily, which described in great detail the island’s homosexual community.

The first great romance of Kuzmin’s life began in 1893. “I met a man, with whom I fell very much in love,” he wrote later. “He was about four years older and an officer in the cavalry … . It was very hard to spend enough time with him, to conceal where we met, etc., but it was one of the happiest periods of my life.” He continued that, although “my mother did not especially approve of my way of life,” it was “an enchanting time, especially because I found a new group of merry friends.”

Other grand passions followed. By 1908, when Kuzmin published Nets, his first homoromantic poetry anthology, he was living with artist and set designer Sergei Sudeikin (1882–1946), who later created the settings for the original New York production of Porgy and Bess in 1935, and his first wife, dancer Olga Glebova (1885–1945). When Olga discovered the two men were having an affair, she demanded that Kuzmin leave their home, although the three of them continued to collaborate on plays and poetry readings.

Apparently, Olga and Kuzmin had the same taste in men. In 1910, when the author was 38 years old, he met Vsevolod Gavriilovich Knyazev (1891–1913), a dashing army officer, who was 19. Their intimacy lasted until he abandoned Kuzmin for Olga two years later. Knyazev committed suicide after Olga left him for Symbolist poet Alexander Blok (1880–1921), a great defender of Kuzmin’s work, then married to actress Lyubov Mendeleeva (1881–1939), whose father, Dmitri Mendeleev (1834–1907), had created the periodic table of the elements.

Kuzman met Yuri Ivanovich Yurkun, née Juozas Jurkūnas (1895–1938), the enduring passion of his life, in 1913; an aspiring writer, he published his first novel, Swedish Gloves, the next year. Even with ever increasing sanctions against gay men in the Soviet Union, they remained together for 23 years. At first, they lived in St. Petersburg with Yurkun’s mother in a communal apartment. In 1920, they were joined by actress Olga Arbenina, who became Yurkun’s wife in 1921. Soon after, he stopped writing to become a successful graphic artist.

As an openly gay literary figure and a prominent spokesman for sexual expression, Kuzmin essentially became a nonperson under Communist authority, which condemned male-male intimacy. For the last decade of his career, he made a meager living primarily as a translator, most notably of Shakespeare’s plays. His final public reading was in 1928, which one contemporary described as “the last rally of Leningrad homosexuals.” He was somehow allowed to publish one more book of poems, The Trout Breaks the Ice, the next year, then nothing.

Two years after Kuzmin died in 1936, Yurkin became caught up in Josef Stalin’s Great Purge of political consolidation. In a notorious case involving more than 70 poets, playwrights, essayists, and journalists, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR sentenced him to death “for participation in an anti-Soviet right-wing Trotskyist terrorist and sabotage organization operating among the writers of Leningrad.” He was executed on September 21, 1938. Olga Arbenina tried for more than a decade to learn of his fate.

Kuzmin hoped for a future where each of us would have the right “to be ourselves,” but instead saw the freedom of literary and artistic expression he had briefly enjoyed steadily collapse around him and sexual openness become more and more suppressed. He was never to know the enlightenment that would lead, as he wrote, to a world where “people saw that every sort of beauty, every sort of love is from the gods, and they became free and bold, and they grew wings.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on May 23, 2024

Recent Comments