By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney–

By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney–

We’ve just returned from a wonderful two weeks in Japan, where we gave talks on marriage equality, HIV/AIDS, and LGBTIQ rights, and met with fellow activists. We spoke to hundreds of students, professors, activists, and businesspeople, who showed great interest. The New York Times recently reported a “’boom’ in LGBT awareness” in Japan, citing recent polling showing that nearly 80 percent of Japanese under age 60 now support marriage equality.

The “boom” was immediately evident to us. When we first gave marriage equality talks in Japan seven years ago, we asked a class of university students whether they personally knew someone LGBT. Barely anyone raised their hand. When we asked the same question two weeks ago, many hands popped up, with one woman telling the class that she knew an LGBT person because, in fact, she was one herself.

Seven years ago, nowhere in Japan offered partnership certificates to same-sex couples. During our trip, Osaka Prefecture, with a population of nearly 9 million people, began issuing certificates, meaning that 20 percent of Japanese now live in places that offer certificates. Although the certificates offer few substantive legal rights, they hold symbolic value not just for the couples themselves but also as a signal to the nation of growing governmental support for LGBT rights. Activists are pressing hard in the lead up to the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics to increase the number of places that offer certificates.

And a year ago, a diverse group of same-sex couples filed marriage equality lawsuits across the country. The influential Japan Federation of Bar Associations, a legal regulatory authority, opined that the country’s current laws excluding same-sex couples from marriage violate the Japanese Constitution.

Last week, the plaintiffs and lawyers in the lawsuits held public events to mark the anniversary. We were delighted to meet some of the plaintiff couples in Tokyo, to discuss our shared journeys, and to provide inspiration to each other. We also met with Kanako Otsuji, the first openly LGBTIQ elected member of the Diet (Japanese Parliament), who last year introduced marriage equality legislation in the Diet.

But substantial barriers to winning equality remain. The conservative government led by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has shown no indication that it would give Otsuji’s marriage equality bill a hearing in the Diet. The Japanese Supreme Court is considered a conservative institution that historically has rarely invalidated legislation as unconstitutional.

In the U.S., the fact that millions of LGBTIQ people have come out has been foundational to the victories our community has won. In Japan, the route to winning equality may differ because coming out remains personally challenging to many Japanese LGBTIQ people.

In the U.S., the fact that millions of LGBTIQ people have come out has been foundational to the victories our community has won. In Japan, the route to winning equality may differ because coming out remains personally challenging to many Japanese LGBTIQ people.

Japanese women face parallel struggles to that of LGBTIQ people. Although Japan boasts the third largest economy in the world, it ranked a lowly 110th out of 149 countries in the World Economic Forum’s 2018 Gender Gap Index. And the country ranked 165th out of 193 nations in terms of women members of representative national legislatures, according to a 2017 study. A few years ago, Otsuji told us that, in some respects, it was more difficult for her to run for the Diet as a woman than as an LGBT person.

On our last night in Japan, we dined with two Japanese friends, who are both successful professionals: one a man, and the other a woman. We ate at a cozy vegetarian Japanese restaurant, tucked away on a winding alley in central Osaka, with just two tables and a few seats around the counter behind which the young owner prepared set meals for his customers. When the owner presented our set meals at our table, an animated conversation in Japanese between the owner and our Japanese friends ensued.

When the flurry of words ended, we asked our friends what had transpired. They explained that the owner had brought our woman friend a smaller serving of rice for the meal, explaining that female customers received less rice than male customers because they needed less food (even though, we note, we all paid the same price for our meals). Despite our friends’ protestations, the owner insisted. Our friends decided not to escalate the disagreement further and simply let it go, leaving our female friend to internalize the anger and frustration she felt.

Earlier, she had explained to us the Japanese term meiwaku. We understand it translates roughly as being an annoyance or causing disturbance to others. Japanese children are taught from an early age not to assert themselves in ways that are perceived as disturbing or troubling to other people. Doing so is considered selfish in a society that values group harmony above all. Our friend confided to us that even though she was completely in the right when it came to receiving the same amount of food as male customers, she, in fact, felt guilty for raising the issue even to the limited degree she did.

Another female Japanese friend told us this type of disparate treatment of women at restaurants is a thing of the past in Tokyo. But this profound societal value of not being meiwaku seems to pose a great challenge to LGBTIQ people coming out and to women’s professional and political advancement.

We do not profess expertise in Japanese societal norms, but it seems that the ability to which LGBTIQ people and women can demonstrate that their full and open participation in society is not meiwaku may be key to personal, political, and professional success—and both metaphorically and literally to getting a fair share of rice.

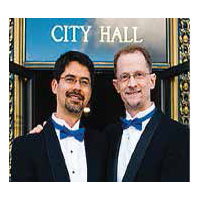

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Published on February 13, 2020

Recent Comments