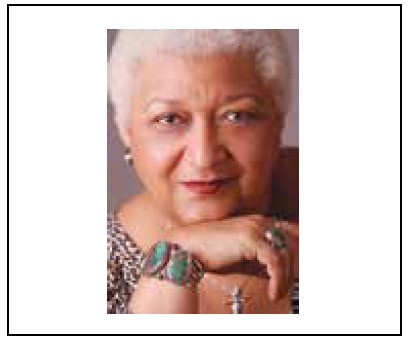

By Jewelle Gomez–

Let’s travel way back to those mysterious times—BE. Before Ellen, that is. Or before Kristen Stewart publicly shifted her affections from the silver-skinned vampire, Robert Pattinson, to a series of charming ladies. Or before Queen Latifah finally acknowledged what we always knew. And while we may hope that one day it won’t matter which initial (LGBTAQ+) you are on in order to work in Hollywood (or anywhere), no one’s holding her breath.

I consumed movies and television like popcorn not realizing then I was looking for my lesbian self. Television and movie images were so influential in the 1960s it’s a wonder that more of us didn’t end up swinging from a ceiling fixture like the typically tragic lesbian played by Shirley MacLaine in The Children’s Hour. Despite those impossibly desperate portrayals lesbians, my generation always had our own media icons, who often weren’t lesbians at all (or at least, for some, not publicly out).

For me, Shirley MacLaine was my first, despite her sad film portrayal. It was her short hair that initially got me; so few female stars wore their hair short at that time. MacLaine also was an iconoclast in her personal life; a supporter of the Civil Rights Movement, and an independent spirit. It was like she was whispering, “I’m not a lesbian, but I could be.”

An earlier star was flinty-eyed Barbara Stanwyck, who had unusually stark white hair. Stanwick’s smoky, crackly, low register voice made you lean in to listen. In her earlier movie roles she was the “bad girl,” but I became her true devotee when she played the matriarch on TV’s Big Valley. She wore a split skirt so she could ride horses and boss around the cowhands. Yes, I know that westerns are mostly monumentally racist and sexist, but as a young girl it was where I most often saw women who were hard drinking, independent, and bossy. (Remember Miss Kitty, the madam in Gunsmoke?) It was just the type I imagined, at ten years old, I was looking for or wanted to be.

The depth of character that Black women actors might portray was often obscured by their skin color; or their toughness was turned into a caricature. Directors sometimes didn’t seem to know what to do with them. Diane Sands, who played the sister in Raison in the Sun, broke all stereotypes playing independence and rebellion. She bounded from floor to furniture, protesting being overlooked in favor of her brother, and raised her voice in a way few female characters were ever allowed to do.

France Nuyen was probably the most femme movie icon whose career I followed. As a teenager I understood she was getting shortchanged in racist movies like South Pacific. However, as a young lesbian I admired the subtlety Nuyen, who was French/Vietnamese/Chinese, brought to performances even when they were designed to be humiliating to Asians and to women. She was never a cartoon figure even when the director might have wanted that.

The ultimate non-Lez icon was Diana Rigg, who starred (way before Game of Thrones) in the British production The Avengers. She often wore mod mini-skirts but is remembered for her leather jumpsuits! As a secret agent in a science fiction-ish government agency, she could do battle against any operative put in her path and barely break a sweat. She was a gold standard Lez icon!

Where other teen friends cut out public relations shots of Sidney Poitier or James Dean, I scoured the movie magazines to collect pictures of my lesbian icons. Looking back, it reminds me of my circuitous path to lesbian-feminism and how many others are on similar, coded paths, even today.

Now I understand it was an essence I was searching for, something that signaled a lesbian “value” to me even if the woman wasn’t one. It was the “bad girl” or outsider stance, a rebellion against female roles, a sense of conscience, and the ability to be hard enough to survive and sensitive enough to outsmart the harsh world surrounding them. I still look for those values in media and in people. Thank goodness for streaming! I love to watch the old movies or TV shows of my Lez icons occasionally; they remind me how they helped me survive.

Jewelle Gomez is a lesbian/feminist activist, novelist, poet, and playwright. She’s written for “The Advocate,” “Ms. Magazine,” “Black Scholar,” “The San Francisco Chronicle,” “The New York Times,” and “The Village Voice.” Follow her on Instagram and Twitter @VampyreVamp

Published on November 18, 2021

Recent Comments