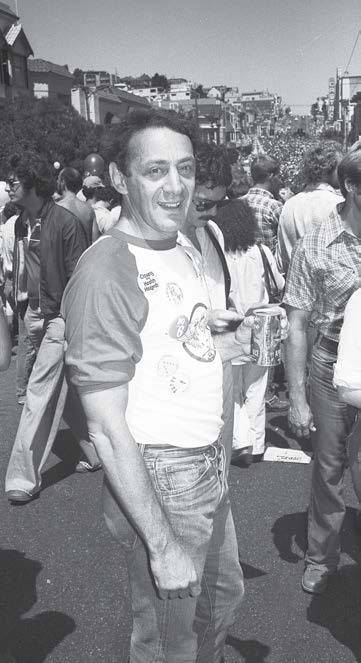

By Tom Ammiano–

I moved to 16th and Castro in 1968. If you walked down Castro Street almost at any time then, you would probably see Harvey Milk physically going about his business either posting flyers or at work in his Castro Camera store. One of Harvey’s flyers that I saw said: “There are businesses in the Castro that you patronize that are homophobic.” Then it listed several stores—one was then called Mike’s Liquors—and urged people to stop shopping there. People did, and they lost a lot of money. Well, guess what? In a week or two the stores said, “Oh, of course we’re hiring drag queens!” They totally reversed course. It was a pure business decision. It was a brilliant, straightforward strategy. What did it take? A little flyer. I f-ing loved it. People underestimated what gay people were really thinking. They thought that we’d be all be docile and just say, “Take my money and discriminate against me. Oh well.”

Harvey came to my attention by doing that. But the most significant thing he did involved standing up to the police. I always had problems with cops and how they treated everybody. In those days straight punks would come into the neighborhood, usually around 2:00 am. They would start to beat up on some poor gay guy. If you called the cops, the cops would come from Mission Station and they would just hassle the gay guy. Then they would hassle you for bothering them.

Harvey Milk stood up to that crap. In the Castro, the queens poured out of the bars around 2:00 am. Of course, it’s a sidewalk culture and people don’t just disperse immediately. They stand around and talk. They’re loaded. They do a little dance then they cruise for somebody to go home with. There was a particular evening when, after the bars emptied, some straight punks pulled up, jumped out of their car, and started to wail on a gay guy. Fortunately, there were some people there who had alarm whistles on them thanks to Hank Wilson distributing them. They started whistling for help—Woot! Woot! Woot!

That drew attention. We all rushed over to where the gay guy was beaten. The straight punks were gone—once the whistles went off, zoom, they left. The cops showed up. But, when they did, their interaction with the beaten-up gay guy was not positive. The cops treated him like he had done something wrong by getting beaten. They were snide to him and all that kind of s–t.

Suddenly, out of the crowd comes the Jewish cavalry, Harvey Milk. He says to the cops, “What are you doing here? Don’t you understand this man needs help? What’s happening?” My heart leaped into my throat. I thought, “I really don’t like cops and I always want to stand up to them but I’m afraid I’m going to get killed if I do that.” Right then and there was almost an epiphany about who Harvey was and who he could be. There are a lot of queens who were very conservative and didn’t like to rock the boat, even over incidents of gay violence. But when it was in your face it was hard to equivocate about it. I mean, the cops were definitely out of line. When I saw Harvey stand up and call the cops out on their s–t in front of everyone I thought, there’s my hero!

One day there was an impromptu march about some anti-gay court decision that had just come down. There were a lot of anti-gay court decisions and laws passing in those days, so take your pick which one it was. There were not a lot of people there, but a bunch of us were milling around Castro Street wondering what to do. Someone finally said, “Let’s march down Market Street and protest!” So, we did. We wound up at Union Square. Then, once again, there was a point where everybody was just kind of milling around. It feels almost like you’re just waiting for someone to take charge. Then Harvey, again, came out of the crowd. He stood up on a little platform in Union Square and gave a speech. That’s what we all wanted. We wanted somebody to step up. It didn’t even have to be the greatest speech in the world. Just that he stepped up.

Harvey was a beacon for liberation. His theme would always be, “We’re not going to tolerate this!” Harvey was a leader who took his lead from the community. He was a conduit for what the people thought and needed. That made a big difference to us.

Harvey was one of the few community leaders who were supportive of the gay teachers’ organizing from the outset. The other gay leaders, so to speak, were kind of Dianne Feinstein-allied establishment people. They would say to me, “Don’t be too gay. Don’t rock the boat.” I always admired Harvey for being there for the gay teachers before it was the easy thing to do.

One time, Harvey came to one of our gay teacher meetings. We had a hard time finding places to meet. Nobody would let us meet at their offices except the Family Service Agency on Gough Street. It was only a few of us regulars there with one new guy from the East Bay. The new guy was handsome—very handsome.

Harvey came to the meeting and we all chatted him up. He had some good ideas then said, “Good luck!” Of course, he also hit on the handsome guy. They went home together. So, thank you, Harvey! This is the combining of the world of politics and real life. That cute guy—we never saw him at another meeting again. But I’m sure he never forgot that one meeting.

When Harvey was running one of his three races, the Alice B. Toklas Club had its endorsement meeting in an older kind of gay bar. It was a very stereotypical group at the meeting. A lot of queens in business suits. Very white. Flocked wallpaper, gilded things. It was a noontime meeting. I think it was a guy named Bob Mendelsohn who was running for Supervisor against Harvey in 1973 and they were both there to ask for the group’s endorsement. Hank Wilson and I went to the meeting together.

People were drinking cocktails. It was the middle of the day. The candidates gave their speeches. I remember Mendelsohn as kind of a nebbish. He said something like, “blah blah blah.” It sounded exactly like that. But he wanted the endorsement. It was important because he was straight and this was a gay club.

Then up comes Harvey Milk. He didn’t yet have his polished speechifying act together in these earlier races. He had the sincerity, but he was more extemporaneous with his speaking style. Some of the people in the audience were drinking and laughing at him. Hank and I were not laughing—we were loving it. We just recognized something very special.

I remember looking over at Hank. He looked at me and our looks both were the same, “This is fabulous!” Even though Harvey fumbled his words, it didn’t matter. It was what he said, not how he said it. Of course, he didn’t get their endorsement. He was one of many progressive gay candidates that did not get the endorsement of the Alice B. Toklas Club.

Harvey had a ponytail then, but it was tied back. He didn’t drink either. In BAGL they were so extreme left in that way where everything is hypercritical. They kind of trashed Harvey. Hank and I stood up as teachers and we said, “Well you know Harvey is really great on gay teachers’ issues.” We defended him. Later we realized that Harvey could take care of himself.

That was the beauty of it. You didn’t have to go around and always defend him. You could just say, “I support him.” That was a great thing. You didn’t have to speak for him. He could speak up for himself. Harvey did have prescience because he talked about transgender issues, he talked about rising housing prices, and the danger of unchecked real estate speculation.

He talked about disabled people. He connected our struggle to other minorities that were disenfranchised. He talked about campaign finance reform and police reform. That was in the early 1970s. There is a tape of him opining on real estate speculation gutting San Francisco’s middle class and talking about how regular people get evicted while the rich get more luxury apartments to live in. It’s amazing—he could be saying that today. I love that too because it was the future. That’s where I think the inspiration came from. Harvey always thought about the future. Even though he didn’t get to live it.

I also thought Harvey was just brave—very brave. When you look back you realize that his positions and his standing up took a hell of a lot of courage. I think people were inspired by that. Maybe you were a little afraid to speak out because you might lose your job. But you could like what Harvey was saying. That’s where his votes came from. That’s how the movement grew. Harvey was speaking for a movement, even though the A-gays and establishment people couldn’t see it yet.

Out of the Crowd Comes Harvey Milk is an excerpt from “Kiss My Gay Ass: My trip down the Yellow Brick Road” through activism, stand-up, and politics, a new book by former California assemblymember and San Francsico supervisor Tom Ammiano. “Kiss My Gay Ass” chronicles Tom’s arrival in San Francisco on a Greyhound bus and follows his journey through the flopsweat trials of professional comedy to the halls of power at City Hall and the State Capitol. Along the way Tom stops everywhere from New Jersey to Vietnam to Hollywood. Published by Bay Guardian Books, “Kiss My Gay Ass” is available for direct mail order at www.kissmygayass.com.

Published on May 20, 2020

Recent Comments