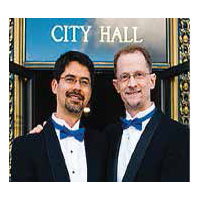

By Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis–

Illinois Senator Richard Durbin called it “shameless”; Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar: a “sham.” They were, of course, talking about last week’s unprecedented U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee hearing to engineer Trump nominee Amy Coney Barrett a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court.

The purpose of the nomination, culminating a decades-long partisan Republican effort to pack the Court with staunchly conservative ideologues, was laid bare by the words of Judiciary Chair Lindsey Graham. Despite Barrett and her Senate allies repeatedly maintaining that her personal views had nothing to do with how she would act as a Justice, Graham proclaimed: “This is the first time in American history that we’ve nominated a woman who’s unashamedly pro-life and embraces her faith without apology and she’s going to the Court … . This has been a long time coming and we have arrived.”

The fact that the nomination is proceeding just days before the presidential election further underscores Graham and his colleagues’ partisan motives. After Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and the Republicans blocked confirmation of President Obama’s March 2016 nomination of centrist Merrick Garland to the Court, Graham promised that “if an opening comes in the last year of President Trump’s term and the primary process has started, we’ll wait to the next election.”

Graham and his fellow Republicans are now reneging on that promise, exposing once and for all their nakedly partisan approach to the judiciary. Their aim is to further their own political power and to cater to the personal interests of their financial backers and political base. They seek not to serve the American people who largely reject much of their radically conservative agenda.

Barrett, with connections to the homophobic hate group Alliance Defending Freedom and far right Catholic group People of Praise, appeared duplicitous herself at the hearing. A key moment came when she claimed it highly unlikely that a case challenging Obergefell, the landmark nationwide marriage equality decision, would make it to the Court.

Barrett simplistically told the Committee that any case challenging Obergefell would first go to lower courts who would have to say: “‘We’re going to flout Obergefell.’ And the most likely result would be that lower courts, who are bound by Obergefell, would shut such a lawsuit down, and it wouldn’t make its way up to the Supreme Court.”

Surely Barrett is aware that the losing party in any such case may simply ask the Supreme Court to hear their case, and if four Justices agree, the Court will do so. Indeed, the State of Indiana right now is asking the Court to take its case challenging the right of married same-sex couples to have both their names on their child’s birth certificate. A Texas case challenging the clear directive in Obergefell that same-sex spouses of government employees have the right to health care and other spousal employment benefits on the same terms as different-sex spouses is working its way through the Texas appellate courts and could reach the U.S. Supreme Court in perhaps two years. And just two weeks ago, Justices Thomas and Alito wrote an opinion all but inviting potential litigants to challenge Obergefell.

This term, the Supreme Court will also decide Fulton v. City of Philadelphia determining whether Catholic Social Services can take local taxpayer money to provide foster care placement services when it flagrantly violates local anti-discrimination laws by refusing to place children with loving same-sex couples.

Barrett throughout the hearings embraced “originalism,” a doctrine by which judges claim to decide cases without considering their own views. Barrett asserted she neutrally interprets the Constitution “to have the meaning that it had at the time people ratified it.” Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot put her view of originalism this way: “You ask a gay, black woman if she is an originalist? No, ma’am, I am not … originalists say that, ‘Let’s go back to 1776 and whatever was there in the original language, that’s it.’ That language excluded, now, over 50% of the country.”

More importantly, most of the Constitution’s actual provisions are, in fact, broad and general because they are intended as fundamental principles to apply to a wide variety of circumstances arising over centuries as society evolves and gains new understandings. The fact that the Constitution’s original drafters made the document exceedingly difficult to amend demonstrates how they intended it to be adaptable and not amended every time something new arose. By contrast, many state constitutions like California’s can be amended by simple majority vote every two years at statewide elections and contain numerous very particularized provisions.

The truly originalist view of the U.S. Constitution has never been more eloquently expressed than in Justice Kennedy’s concluding paragraph of Lawrence v. Texas, the case that finally ended the criminalization of the physical expressions of queer love:

“Had those who drew and ratified the [Constitution] known the components of liberty in its manifold possibilities, they might have been more specific. They did not presume to have this insight. They knew times can blind us to certain truths and later generations can see that laws once thought necessary and proper in fact serve only to oppress. As the Constitution endures, persons in every generation can invoke its principles in their own search for greater freedom.”

Those words remain the highest law of the land today: a search for ever greater equality and freedom. We must stand up for our lives now more than ever to try to keep those words and the promise of the Constitution alive.

Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Published on October 22, 2020

Recent Comments