By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

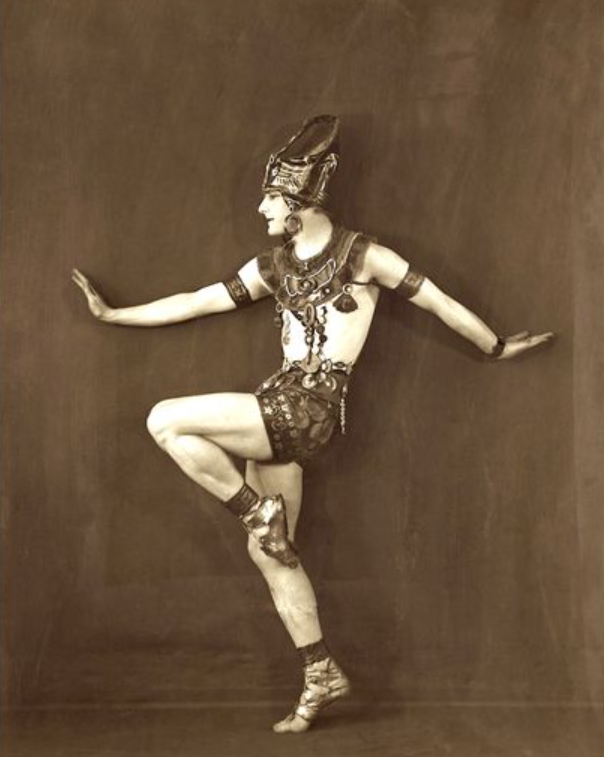

He was called “a modern Leonardo da Vinci,” “America’s most eminent exponent of classic dancing,” and a man who “follows most of the seven arts and does more in any one than most in their individual specialists.” Admirers described him as “a reincarnated Greek god” and “the Most Beautiful Man in the World.” He was so famous that theatergoers readily understood Adele Astaire when she upbraided her brother, Fred, in George Gershwin’s 1927 musical Funny Face, “As a Paul Swan, you are not so hot.”

During his long career as a sculptor, painter, muralist, poet, and dancer, Paul Swan was very hot indeed. Born in Ashland, Illinois, in 1883, he was raised in Crab Orchard, Nebraska, America’s heartland. He was a sensitive, artistic child and his family did not approve of his “strange quirks” and “unconventional behavior.” He chose his euphemisms carefully in a 1917 interview, when he described them as people who “are very orthodox and do not believe in the life I have chosen. They believe it wrong to cultivate personal charm.”

After completing his studies at the Art Institute of Chicago, Swan moved to New York, where he found work as an illustrator for the Butterick pattern company. His great opportunity came when he was inspired to do a life-sized painting of the great Russian-born actor Alla Nazimova in 1910, which he sent to her as a gift. She immediately put it on display in the lobby of her 39th Street theater, then commissioned him to create portraits of her as Henrik Ibsen’s most famous heroines.

Nazimova’s patronage enabled him to travel first to Egypt and then to Greece, where he studied with sculptor Thomas Thomopoulos and began to explore dance, which he called “sculpture in motion,” as another way to express his ideals of the beautiful. Soon after, he performed at a gala organized by Thomopoulos, where his reception was nothing less than astounding. One journalist wrote, “No foreigner since Lord Byron has ever received such public acclaim.” Another, even more beguiled, called him “the reincarnation of one of our lost gods.”

From then on, both dancing and art became his life’s passions. Described as an “aesthetic dancer,” he preferred using freeform movements and compelling gestures, not precise and highly formalized, traditional steps and structures to share his ideas. “I dance to express those subtle emotions and hidden meanings,” he explained, “which help us to feel that life is somehow good and beautiful, and pass the news along.” Even though he rejected conventional performance, he became known as “America’s leading exponent of classic dancing.”

He was also being called, “The Most Beautiful Man in the World.” In 1913, the Burlington Weekly Free Press wrote, “When one first sees him an involuntary exclamation bursts forth, ‘Surely a Greek God in the flesh.’” “His popularity,” the newspaper proclaimed, “is second to none and he is worshipped by every class of men and women from high society to the Suffragists, for whom he appeared in public twice last winter with only a leopard skin to cover him.” If not his favorite costume, then it was certainly his most reported.

An article published under his name the next year explained why his appearance was so esteemed. In “my childhood I realized that I was gifted with the Greek type of beauty, and it has been my aim to cultivate this to my utmost.” He believed “the most perfect type of manly beauty” could be seen in the Hermes of Praxiteles, “whom some of my friends have been kind enough to compare with me,” and a statue of Antinous, “the favorite of the great emperor Hadrian.”

Physical beauty was not enough, however. In addition to “exercise and right living … it must be said that beauty cannot exist unless the figure is inspired with grace and the poetry of motion. The face, too, must be intelligent and illuminated with the yearning for the beautiful,” and he urged “all boys and young men to keep the Greek ideal of beautiful before them.” If “we all loved true beauty,” he concluded, “the sin and ugliness that disfigure humanity would be impossible.”

According to Winnifred Harper Cooley, writing for the New York Sun, he really was that beautiful. “He is molded in perfect proportions. His face is as exquisite as if chiseled by Phidias for the youthful Apollo. The features are clearly cut as a cameo, the eyes blue and expressive, the hair soft and waving, of a pale brown, the brows direct and earnest, and the face glowing with the sunrise color. It is not merely the regularity of line that attracts, but the spiritual glow which animates every moment.”

At a time when notions of the ideal man were changing for many Americans, there were questions about his manliness. (His sexual desires were never discussed openly.) “Of course I have been maligned and abused and persecuted,” Swan told Cooley, one of the first women to call herself a feminist, “but the only thing I really want to impress upon people is that I am not abnormal or eccentric. Why should one be regarded as a freak because he admires the beautiful?”

Cooley understood that it was “necessary for me to impress upon the skeptical that there is nothing mystical or uncanny or abnormal about [him], although it will be impossible to convert the plain, commercial, unpoetical American business man to any toleration of male beauty, or to convince him that one whose entire life is spent in the expression of beauty through dancing and painting is other than effeminate and contemptible.” Whether or not she was aware he was bisexual is unknown.

Swan began appearing before the public just as the image of the male ideal was changing. The new man “will be handsomer because he will be more harmoniously developed,” Elizabeth Aldrich wrote in The Omaha Daily Bee. An ardent suffragette, she stated, “The forces which have changed the traditional life of women are also changing the traditional life of man. While these forces are developing in her self-reliance and independence of thought and action, they are making him a kinder, more tender, more imaginative creature.”

Those forces were also making him appear increasingly androgynous, personified on magazine covers by the suave, cultured, immaculately tailored men painted by J. C. Leyendecker and glorified by such film idols as Rudolph Valentino, Ramon Novarro, Antonio Moreno, John Gilbert, Charles Farrell, and even the doe-eyed “It Boy” Gary Cooper. “These prettier, more effeminate male stars,” wrote historian William J. Mann, “represented a new era, when sexual ambiguity represented culture, culture inspired success, and success was considered sexy.”

These views changed during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when the values of the Roaring Twenties, blamed in great measure for the country’s economic and social ills, were largely repudiated. Once again, men were supposed to be masculine, virile, with all their traditional attributes—hardworking bread winners (when they could find a job), husbands, and fathers—not sexually ambiguous “sophisticates.” Women were expected to be housewives and mothers, not urbane socialites. Clark Gable replaced Novarro as MGM’s biggest star. Cooper became a strong, silent “hero on horseback.”

Swan continued to make New York his base of operation until the early 1930s, when he moved to Paris, which had adored him early in his career and continued to do so as both a dancer and an artist. Les études Poetique called him an “incomparable virtuoso” and he won awards from the Salon de Artistes for his sculptures, including one of composer Maurice Ravel, now lost. The war in Europe forced him to return to the United States in 1939.

With his studio again in New York, Swan continued to work in the fine arts and present weekly dance recitals for another 20 years. In 1960, Life magazine lauded him as an “all-around man in the arts,” but by then critics considered his work old-fashioned and his renown faded. Five years later, when he appeared in two experimental films by pop artist Andy Warhol, Paul Swan and Camp, he complained, “I am the most famous unknown person in New York.” He died in 1972 at the age of 88.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Face from Our LGBT Past

Published on July 25, 2024

Recent Comments