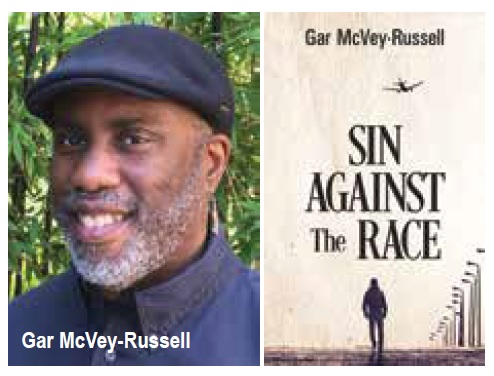

Michele Karlsberg: For this issue of the San Francisco Bay Times, I present a guest article written by author Gar McVey-Russell.

“When I was in the closet, I thought of myself as living inside a bubble made of one-way glass. I could see out, but others could only see their own projections of who they thought I was.”

Alfonso Berry from Sin Against the Race

Read between the lines of my novel Sin Against the Race and you’ll find Ralph Ellison. His masterpiece Invisible Man—the story of a black man who exists only as a prop for other people’s manipulation—has informed me since my teenage years.

It sat enticingly on a bookshelf in my family’s house for years. And despite wishing otherwise, I knew it was not the offspring of H.G. Wells’ similarly-titled novel. Ellison’s nameless narrator confirms this in the prologue:

“No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms.”

The narrator describes himself as a man of flesh, bone, blood, a mind, and then adds that he is invisible, “simply because people refuse to see me.”

Those words haunted me more than any ectoplasm ever could. Scared to read about how the world viewed me and people like me, I put the book down. It sat untouched for months. Like most black folks, I had my share of “race” stories even as a teen: my brothers getting hassled by the police for playing with walkie-talkies, thinking something sinister lurked behind their nerd-play; a Dutch pen-pal who stopped writing after I sent him my photo; a white friend at school who made fun of my flat nose. These and more were all introductions to otherness.

Those words haunted me more than any ectoplasm ever could. Scared to read about how the world viewed me and people like me, I put the book down. It sat untouched for months. Like most black folks, I had my share of “race” stories even as a teen: my brothers getting hassled by the police for playing with walkie-talkies, thinking something sinister lurked behind their nerd-play; a Dutch pen-pal who stopped writing after I sent him my photo; a white friend at school who made fun of my flat nose. These and more were all introductions to otherness.

When I finally committed to reading Invisible Man, I found something unexpected early in the book: “… the winding road past the hospital, where at night in certain wards the gay student nurses dispensed a far more precious thing than pills to lucky boys in the know.”

Prior to reading Ellison, I had dared just once to look for my queer self in a book. Unfortunately, I looked in The Joy of Sex. Its denunciation of homosexuality reinforced my self-hate, the author’s evil intent, and slammed the closet door in my face.

Ellison pried it open and filled me with hopeful questions. What “far more precious thing” did those nurses dispense? Would they dispense it to me, if I summoned the courage to ask?

Invisible Man taught me that “otherness” can lead to an identity crisis, but also that “otherness” is imposed by the larger society. In other words, it’s their problem that I’m black and gay, not mine. Soon after coming out, I found Joseph Beam, Marlon Riggs, Essex Hemphill, Assotto Saint, Billy Strayhorn, and others who refused to remain invisible. I learned from their example that invisibility, like silence, equals death.

In Sin Against the Race, I attempt to peel back the mask of invisibility for those who wear a lavender veil as well as a black one.

Gar McVey-Russell began writing early in life, but thought he wanted to be an astronomer. At UCLA, he co-created a left-leaning paper called “Free Association.” He also wrote commentaries for “The Daily Bruin” and feature articles for the LGBTQ newsmagazine “Ten Percent,” for which he received an award. He began fiction writing in the early 90s. His work has appeared in “Sojourner: Black Gay Voices in the Age of AIDS” (1993), “Harrington Gay Men’s Fiction Quarterly” (vol. 7, Num. 3, 2005), and other publications. He published his first novel, “Sin Against the Race,” in October 2017. He is married and lives in Oakland.

Michele Karlsberg Marketing and Management specializes in publicity for the LGBT community. This year, Karlsberg celebrates thirty years of successful book campaigns.

Recent Comments