By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

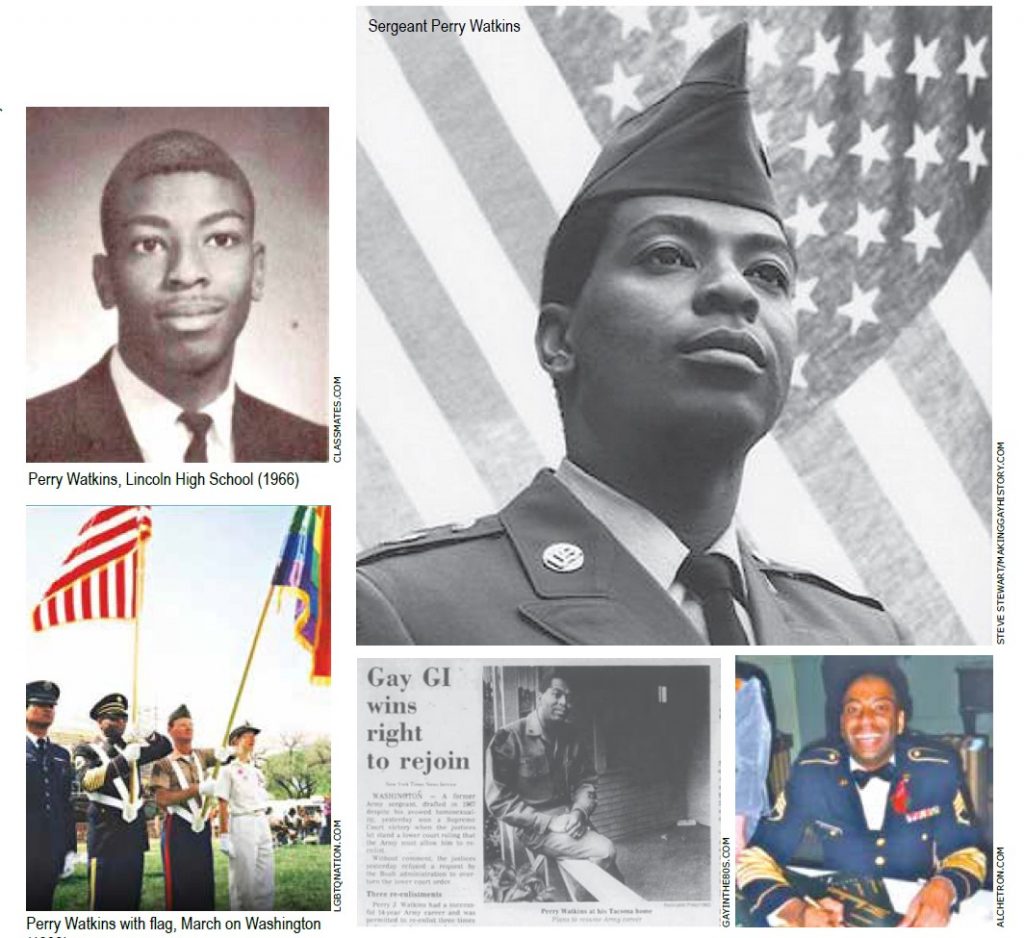

Perry Watkins knew from an early age that he was gay. His family knew. His friends at school in Tacoma, where he grew up, knew. Even the United States Army knew. Always open and truthful about himself, he told them when he filled out the paperwork for his required Selective Service physical in 1967, marking yes to the question, “Do you have homosexual tendencies?” He told them again at the induction center when he was called up for service in 1968. The Army did not seem to care.

Although the military did not have a policy that specifically forbade gay men and lesbians from serving until 1982, the mere possibility of same-sex intimacy disqualified them from joining its ranks. According to a Pentagon statement in 1966, “The presence of homosexuals would seriously impair discipline, good order, morals, and the security of our armed forces.” Even the rapidly escalating need to conscript troops for the war in Vietnam did not change this official position, although it encouraged some recruiters to look the other way.

During his induction examination, Watkins was evident about his sexuality. Asked by an Army psychiatrist why he had checked “homosexual tendencies” on his questionnaire, he specified the intimacies he enjoyed with other men. That led to a second interview with another psychiatrist, who verified he “has had homosexual tendencies in the past,” but was now “qualified for induction.” Watkins, a self-acknowledged sexually active, openly gay Black man, became a duly recruited, openly gay member of the United States Armed Forces.

When he completed basic training, Watkins joined a program to become a chaplain’s assistant. He had attended classes for less than two days when the school’s commandant told him, “You can’t complete this course, because you’re an admitted homosexual.” Watkins then demanded his release from the service, but he never received it. “Too queer to be a chaplain’s assistance, but … not too queer to be in the Army,” Watkins found that his superiors apparently could not determine “that he was indeed homosexual … enough to warrant a discharge.”

The year after he completed his first term of service, Watkins decided to enlist for a second term of service. Except as a female impersonator on weekends, he had been unable to find a good job. Besides, he wanted the educational opportunities the military could provide him. Once again, he told the Army’s recruiters he was gay. Once again, they reviewed his service record, which confirmed that he was “a practicing homosexual,” and accepted him as “eligible for reentry on active duty” for three more years.

This time, however, he brought company: his drag persona Simone. As with everything in his life, Watkins made no secret of Simone, who was to perform in Army clubs across Europe. She was not the first female impersonator to entertain the troops, but she certainly became the most famous and most successful of her era. Stars and Stripes, the military’s daily newspaper, gave her a rave review, writing, “She Makes the 56th Artillery Brigade Flip.” Simone even won an Oktoberfest beauty pageant, the only contestant born male.

During his second tour of duty, Watkins continued to live as an openly gay man and he continued to tell his superiors the truth about himself. In 1972, however, his sexuality became an issue twice for the Army. First, he was denied a security clearance because, as a known homosexual, he could be blackmailed by enemy agents. It took time, but Watkins eventually convinced the higher-ups that nobody could threaten to “out” someone who was “out” already. He got his clearance.

Not long afterwards, Watkins was investigated because a “confidential informant” had told the Army Criminal Investigation Division (CID) that he was gay, something the Army had known for five years. The CID found lots of evidence of Watkins’ homosexuality, but finally ended its inquiry because he refused “to furnish any investigative leads,” meaning he declined to “name names.” At the end of his second tour in 1974, Watkins reenlisted for another six years.

The Army discovered yet again in 1975 and 1977 that Watkins had “homosexual tendencies,” but allowed its “favorite drag queen” to enlist for a fourth tour of duty in 1979. “There is no evidence,” one review board concluded, “suggesting that his behavior has had either a degrading effect upon unit performance, morale, or discipline, or upon his own job performance.” Soon after, it revoked his security clearance once again, primarily because he did “not deny that he is a homosexual,” a truth he had confirmed repeatedly.

Once again, Watkins appealed the decision. When he heard nothing back for many months, he filed a lawsuit in federal district court to have his clearance reinstated. The military was not pleased. It responded with a notification that it had initiated action to recommend his discharge. In October 1982, the Federal District Court found in Watkins’ favor, but the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision the next year. Watkins was separated from the service at the end of his enlistment period in 1984, 16 years after his induction.

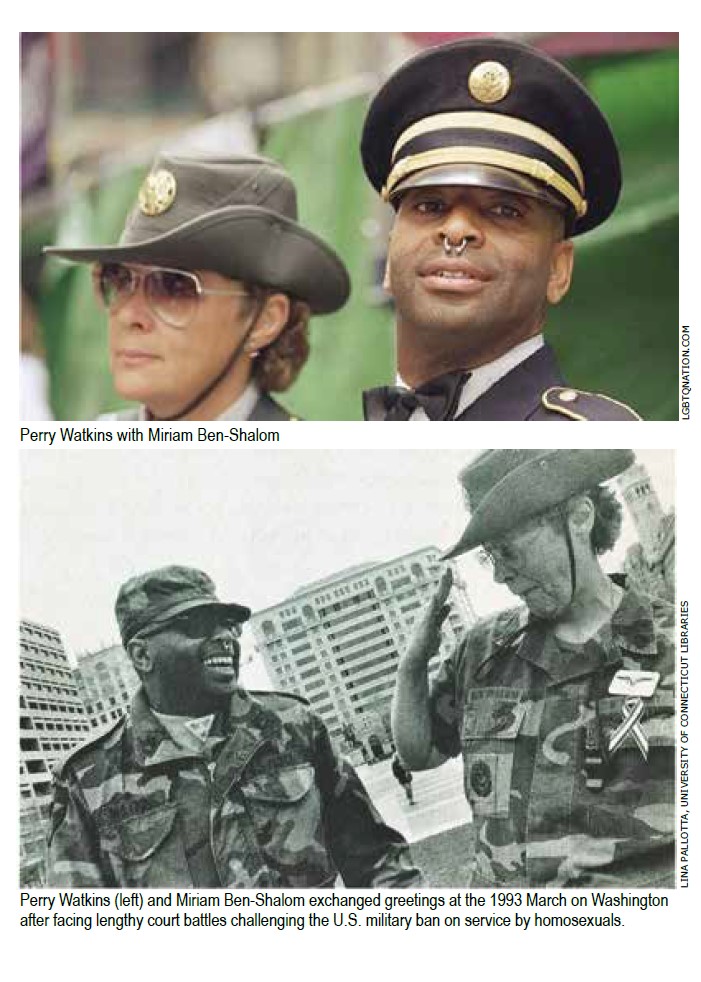

Watkins challenged his discharge in court, arguing that the military’s policy of excluding gays and lesbians was unconstitutional. In 1989, the Ninth Circuit Court finally agreed with him in Watkins v. United States Army, stating that “the exclusion of homosexuals from military service violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,” a decision the Supreme Court declined to review. For the first time, the Army was ordered to return an openly gay man to active military duty after dismissing him for homosexuality.

After the decision, Watkins initially planned to reenlist, but instead accepted a retroactive promotion to sergeant first class, $135,000 in back pay, full retirement benefits, and an honorable discharge. Dying of complications from AIDS on March 17, 1996, he did not live to see the transformations that now allow openly gay men, lesbians, bisexual and transgender men and women to serve in the military. Because of his frankness, courage, and perseverance against hypocrisy and homophobia, he helped to make the changes happen, moving equality forward for us all.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on February 24, 2022

Recent Comments