By Marsha H. Levine–

What’s your Pride experience? A day of fun, usually in the sun and with friends, listening mostly to queer music or dancing?

This is typically how we celebrate ourselves at our commemorations of the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969 that occurred in New York City and was a catalyst for the birth of the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement. Every year we take mainly to the streets in a show of visibility, acceptance, and messaging our struggle for equity—largely peaceful, yet very political.

That’s the commonality of Pride in the United States, and in countries where they enjoy freedoms and progressive governments.

But what is Pride like where lawmakers are conservative, statutes are designed to punish you for whom you love, and religion heavily gatekeeps against what they view as sinful and unnatural?

I had a chance to find out last summer, when Tom Bily, then the director of Prague Pride, invited me to attend their Human Rights Conference held during the week of their festivities. With the participation of Julia Maciocha of Warsaw (Poland) Pride and several other panelists from previous Eastern Bloc nations, I got a peek into what being LGBTQ+ is like in countries that still feel the heavy-handed influence of Russia and Vladimir Putin, despite their independence from Communism and occupation about 30 years ago.

Superficially, Prague appeared similar to San Francisco while Pride was ongoing—lots of queer folks walking around day and night, the city busy with tourism. Even during my travels as I did a little sightseeing, you could hear the loud, thumping music coming from the festival site, as it echoed across the Vltava River from Letna Park. Rainbow flags were abundant, people dressed in bright colors … I would have never thought anything was any different from what I experienced at home. That is, until the first day: the first session of Prague Pride’s Human Rights Conference.

Host Bohdana Rambousková, local activist, started things off rousingly, and introduced Prague Pride Festival Director, Bily, who welcomed guests, both local and from Central and Eastern Europe. Keynote Speaker Klára Šimáčková Laurenčíková, Government Commissioner for Human Rights, shared some of the work she has been doing since being in office, and explained that Prague still has a long way to go to gain LGBTQ+ equality, and we must not be complacent, accepting only what strides have been made in the last couple of decades.

I really had no idea what to expect, given that the only Prides I have attended were U.S.-based, except for a casual march in Montpellier, France. The whole audience was present for the initial panel discussion: Is Europe Still a Safe Space for LGBT+ People? A curious question, I thought, when the only Europe you know are progressive countries like England, France, Germany, and Spain. You might be unaware of just how different things can be when traveling in Poland, Vienna, Hungary, and Slovakia, just to cite a few. More dire yet if you visit Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Ukraine.

With a large ILGA Europe Rainbow Map projected behind them, speakers from Prague, Warsaw, Hungary, and Slovakia spoke to the lack of substance actually reflected by the numbers posted on it. They said that these were based on a survey that supposedly asked basic questions like, did they feel comfortable holding hands with their lover while walking in public. Considering that, even here in America, there are some places where two women or two men holding hands and showing affection might evoke a violent reaction, either verbally or physically, how is this a good measure, especially in more conservative locations? Is there a distinction made between urban and rural communities, where the latter might find less tolerance amid the townsfolk?

Just as we have our own little enclaves here in Provincetown, Greenwich Village, and West Hollywood, and as was likely during August in Prague, one might feel safe on the streets during Pride week. But, as recently as this past September, during EuroPride in Belgrade, the Serbian Prime Minister, Ana Brnabić, announced mere days before that the EuroPride march would not be allowed to take place. Tensions amid threats from far right and anti-gay groups had scaled up in the weeks preceding, until the Minister finally forbid the march over alleged “security concerns.” Thanks to LGBTQ+ protests, vociferous complaints, and a lot of lobbying, the march was allowed to happen, with a guarantee of police protection, and was conducted mostly peacefully and without incidence.

At the Pride Voices event one night in Prague, a showcase of five people relating their stories of growing up LGBTQ+ in challenging societal climates, you heard many of the same threads some of us experience everywhere: no support from parents, sometimes outright rejection; forced to be homeless and live on the street, making a living in underpaid and risky businesses, only to find a circle of friends that had become their chosen family, as they aimed for their dreams. The resources that many American cities have developed to help LGBTQ+ youth might still be expanding, but in a country where dictators and regressive rule once (or still today) exist, there is a long way to go in preventing suicide or other death of those estranged from the usual systems—and love.

More so, sitting down with these presenters after the performance, as they relaxed with what looked like awesome beers (I never got the hang of drinking them), we talked about how differently life is in Central and Eastern Europe than in the places most tourists identify simply as “Europe.” Systemic racism exists, even amid the various white-appearing races of the Slavs. Many of those countries and Pride organizations bordering on or near Ukraine are actively engaged in providing aid to those displaced, helping physically or financially, and this is in addition to both their livelihoods and planning their local Pride events. One young woman described the steps she has to go through to procure much needed medication for Ukrainian Trans military members, whose supply had been cut off by Putin and Russian forces. The word subterfuge came to mind, and I just shook my head in amazement.

We talk about “putting our lives on the line” for the cause in the U.S., mostly by going to protests and demonstrations where there might be the anticipation of violence, but here, almost 6,000 miles away, I was sitting with living examples of Pride organizers who were literally risking everything to help their chosen kin off in a ravaged country struggling to remain independent. Some of them were slipping over borders to deliver much needed funds or medication into secure hands. I was still awed by this information when, a day later, I headed to a historic section of Prague to meet Tom and Julia, and other friends I had made, at the step-off point for the Pride Prague Parade.

All Pride parades might seem a little similar, people milling about as they line up, more rainbows and rainbow flags, colorful garb, fancy face painting, and signs (many of which I could not read). In Prague, they did not allow vehicles in their Parade, which was an immediate difference. But the lack of floats did not diminish the message, or the music! Many were inventive with bicycles, carts, wagons, or hand trucks carrying generators and sound equipment or small karaoke systems.

While groups did have their own banners, each themed section of the Parade was heralded by a numbered sign and designation. Sponsors and businesses were set apart. Political groups marched, as did groups of kink and fetish. There were families, educational institutions, etc. Rather than a mix throughout the whole Parade, sections were arranged by affinity. I followed some of the marchers toward the festival, but the skies were turning gray and threatening, and I had an early train to Vienna to catch in the morning. So, I took one more look around at the city that had become so familiar before heading back to my hotel and my last regional meal.

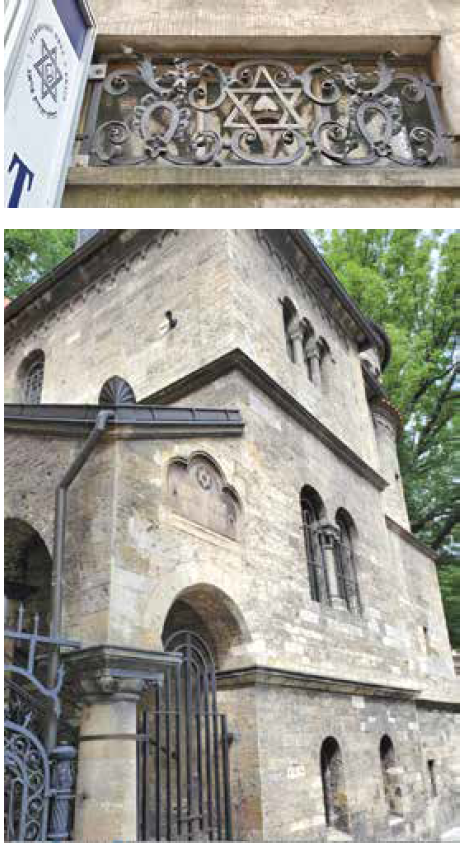

What was doubly important to me during this trip was the long history of Judaism and Jewish people of Prague (and Eastern Europe) that I explored in between the Conference and the Parade. I come from family now represented by Moldova, Ukraine, Russia, Poland, and Vienna, places that once folded into Bessarabia. This was as close to the home of my people I was likely to get. Alas, my poor planning left me with only the Sabbath to tour the remaining original neighborhood. But I was able to gaze upon facades of synagogues, apartment buildings constructed with Jewish stars impressed into building flourishes and on wrought iron gates or balconies.

It has been found that as early as the 10th century, Jews lived in Prague, and at one point one-quarter of the population of Czechoslovakia was Jewish. But during the period of Nazi occupation, almost the whole population of the city was eradicated, either through poor conditions or extermination in the various camps and ghettos. This was sobering to reflect upon, as the next morning, my train hurtled toward Vienna, passing fields of Jerusalem artichoke, round stover hay bales, and tall hills along the southern part of the country.

It did make me ponder some of the parallels between both cultures I’d taken in on this trip, and whether both would be pushed back into darker times than they currently experience. And I thought, is time turning in America, or does the LGBTQ+ community have enough fight within them to keep pushing forward? Funny how a visit far away made me want to become engaged more at home. While it’s fun to party with my friends, my time is better spent volunteering to make things better, even if for just one person.

Marsha H. Levine (she/they/ey) is the Community Relations Manager at San Francisco Pride, of which they have been a consistent member for more than 37 years. Marsha also founded InterPride, the International Association of LGBTQ+ Pride Coordinators, in October 1982, and currently serves as one of their Vice Presidents of Global Outreach & Partnership Management.

Published on February 23, 2023

Recent Comments