By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

After Clement Clarke Moore’s beloved poem “The Night Before Christmas” appeared, anonymously, in 1823 as an “Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas,” Santa Claus cruised from the printed page into the collective consciousness of Americans, fully formed and forever steadfast. The reindeer were there, too, and the sleigh full of toys, but many details were missing. Cartoonist Thomas Nast added the home at the North Pole and the toy workshop in an 1866 drawing for Harper’s Weekly. Others bestowed the elves—and a wife.

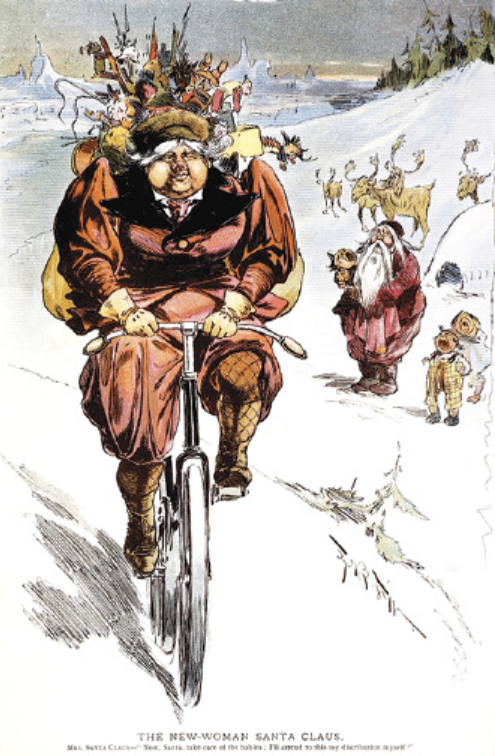

Mrs. Claus first appeared some 20 years after Moore’s poem. Usually described as a smiling, good natured, stay-at-home helpmate who offered her husband comfort and cookies following a long day, she was content to remain in the background while he received all the accolades. Occasionally he acknowledged his debt to her, but in most stories, it was Santa alone who spread the joy and reveled in the adoration he received, while she waited patiently for him to return.

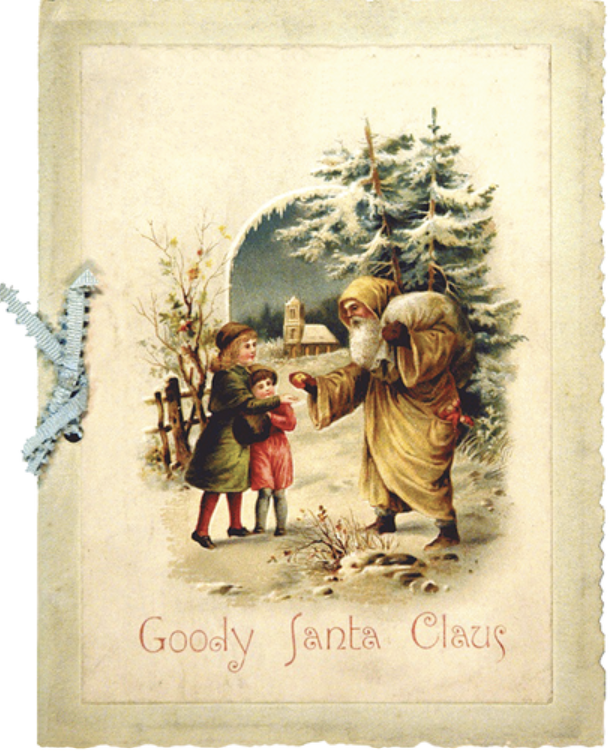

Not until Katharine Lee Bates (1859–1929) published “Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh-Ride” in the 1888 Christmas issue of the children’s magazine Wide Awake was she portrayed as a woman who knows who she is and is not afraid to speak her mind. During an era when women’s rights and privileges were severely limited and they were mostly expected to provide their husbands with a clean home, well prepared meals and well-behaved children, she is a feisty, resolute, outspoken feminist who demands recognition and respect as an equal partner:

“Why should you have all the glory of the joyous Christmas story,

And poor little Goody Santa Claus have nothing but the work?”

This Mrs. Claus is not the shy and delicate creature of Victorian romance novels, retiring to her fainting room for a lie down after experiencing “a touch of the vapors.” A woman who knows her mind and her worth, she is not reluctant to tell the “head of the household” exactly what she thinks of him and the way he regards her:

“You just sit here and grow chubby off the goodies in my cubby

From December to December, till your white beard sweeps your knees;

For you must allow, my Goodman, that you’re but a lazy woodman

And rely on me to foster all our fruitful Christmas trees.”

In the world Bates describes, elves do not make the children’s toys. They grow on trees, which Mrs. Claus nurtures and harvests with no help from Santa. He would simply fail, she tells her husband, without her expertise and industry:

“While your Saintship waxes holy, year by year, and roly-poly,

Blessed by all the lads and lassies in the limits of the land,

While your toes at home you’re toasting, then poor Goody must go posting

Out to plant and prune and garner, where our fir-tree forests stand … .”

Who but Goody knows the reason why the playthings bloom in season

And the ripened toys and trinkets rattle gaily to her feet!”

For her there is no such thing as “women’s work”:

“Home to womankind is suited? Nonsense, Goodman! Let our fruited

Orchards answer for the value of a woman out-of-doors.”

Women, she tells him, can do anything men can. If Santa thinks otherwise:

“Why then bid me chase the thunder, while the roof you’re safely under,

All to fashion fire-crackers with the lighting in their cores?”

Goody Claus wants only to go with Santa on his Christmas Eve trek. Regarding his wife with a certain amount of chauvinism, he at first resists, then finally agrees, although he will not allow her to help with his task:

“Would it be so very shocking if your Goody filled a stocking

Just for once? Oh, dear! Forgive me. Frowns do not become a Saint … .

Yes, I know the task takes brain, Dear. I can only hold the reindeer,

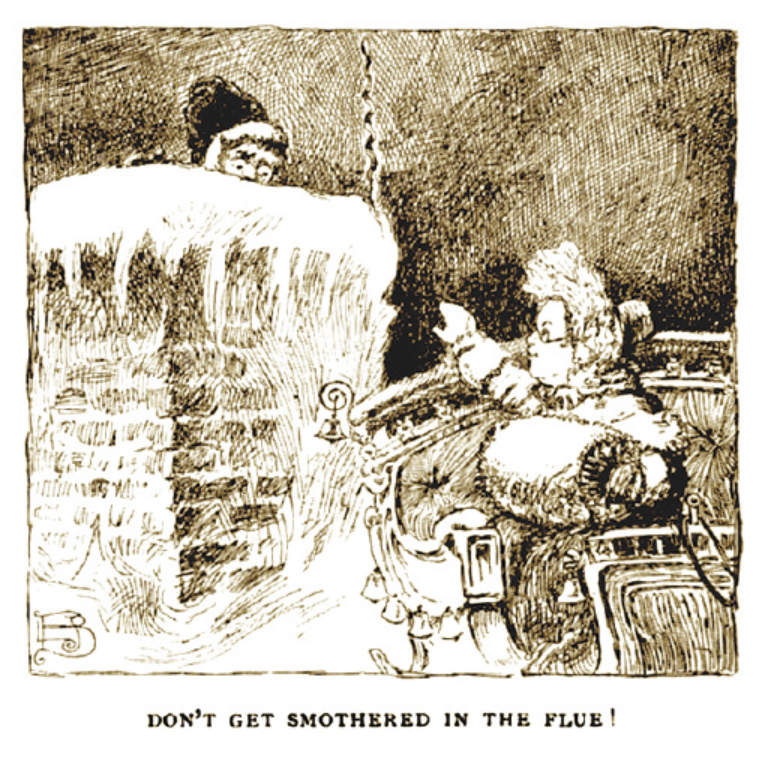

And so see me climb down chimney—it would give your nerves a shock.”

Toward the end of his long journey, Santa encounters an unsolvable problem: a child who cannot receive any presents because his Christmas stocking has a hole in it. Only Mrs. Claus can provide the solution, proving she can do anything he can do—and everything he cannot:

“I’ll mend that sock so nearly it shall hold your gifts completely.

Take the reins and let me show you what a woman’s wit can do.”

She does, too, first mending the sock with “an icicle for needle” she has “threaded with the last pale moonbeam,” then going down the chimney herself to deliver the parcels. All ends well:

“Joy-bells ring in every steeple,

And Goody’s gladdest of the glad. I’ve had my own sweet will.”

At the time “Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh-Ride” appeared in 1888, Bates was an Instructor of English at Wellesley College. Across her distinguished career, among other accomplishments, she created one of the nation’s first courses in American literature and was the first woman to write a textbook about it. A lifelong social activist and ardent feminist, she was an ally of labor unions and a foe of imperialism who worked to improve the condition of women, workers, people of color, and immigrants.

In the summer of 1893, Bates traveled to Chicago, where she joined her dearest Wellesley colleague, history and economics professor Katharine Coman (1857–1915) at the great World’s Columbian Exposition. Its once gleaming white walls were turning a sooty gray by then, but Bates imagined an “alabaster city” of the future. The couple then traveled through “amber waves of grain” to Colorado Springs, where they had been invited to teach at the new Colorado College. Bates especially was moved by the “purple mountain majesties” of the Rockies.

On their journey home, Bates began putting her impressions and thoughts into a poem she titled “America the Beautiful,” which she published in 1895. With music by Samuel Ward, it almost became the country’s national anthem, but in 1931, Congress chose “The Star-Spangled Banner” instead. Its tune was borrowed from a British drinking song, “To Anacreon in Heaven,” a paean to the ancient Greek poet whose verse often praised the beauty of young men and the pleasures of same-sex lovemaking.

At Wellesley, Bates and Coman lived together in what some called a “romantic friendship” or a “Boston marriage,” an emotionally intimate relationship that endured for 25 years. Did they also share a physical affection? No one knows. Most of their personal correspondence was destroyed, although one letter that still exists from early in their affinity describes a deeply felt closeness: “You are always in my heart and in my longings,” Bates wrote to her.

After Coman died in 1915, Bates began writing Yellow Clover: A Book of Remembrance, privately published in 1922. Dedicated to Coman, its poetry clearly and openly describes her feelings toward her life partner. It is “one of the most anguished memorials to the love and comradeship between two women that has even been written,” author Judith Schwartz noted, adding that “it is obvious from the yearning desire that glows throughout the poems” that they “were a devoted lesbian couple.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on December 19, 2024

Recent Comments