By Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis—

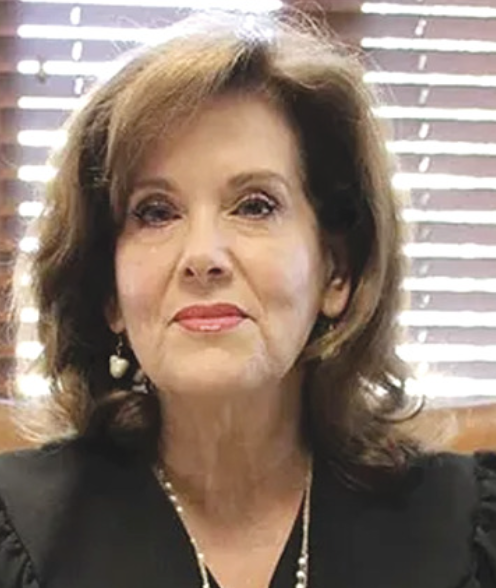

Late last December, Waco, Texas, Justice of the Peace Dianne Hensley filed a federal lawsuit, claiming she had the right to refuse to marry same-sex couples because of her religious beliefs. As part of the lawsuit, she also argued that the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2015 Obergefell decision establishing nationwide marriage equality should be overruled.

The filing garnered some headlines, reporting a new threat to Obergefell. One outlet termed Hensley “the new Kim Davis,” referring to the notorious Kentucky county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples for religious reasons back in 2015 and who last year asked the Supreme Court to overturn Obergefell but was rebuffed.

We take any effort to undermine marriage equality very seriously—indeed, no one should be trying to undercut our fundamental constitutional rights. And we look behind the headlines to try to understand the exact nature and status of any possible threat. At present, we don’t consider Hensley’s case as a likely direct threat to Obergefell itself.

As we’ve discussed previously in this column, nothing currently suggests that a majority of the Court would vote to overturn Obergefell. Hensley argues that the reasoning of the 2022 Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade means that Obergefell should be reversed as well. The Dobbs majority, however, made clear: “to ensure that our decision is not misunderstood or mischaracterized, we emphasize that our decision concerns the constitutional right to abortion and no other right. Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.” The Court was explicit in saying that these rights and precedents include same-sex couples’ fundamental right to marry recognized in Obergefell. The majority stressed that its assurances were “unequivocal” and that any suggestion that Dobbs “will imperil” rights such as marriage equality is “unfounded.”

Hensley’s lawsuit, whose head-spinning procedural history goes back over a decade, focuses on her pursuit of a religious exception to her obligations as a Justice of the Peace. When Obergefell was decided in 2015, Hensley initially stopped performing any marriages, but, in 2016, began marrying only heterosexual couples, citing her religious beliefs. She referred same-sex couples to other officiants, some of whom were nearby, but others not even in the city of Waco.

In 2018, the Texas State Commission on Judicial Conduct, an independent constitutional state agency composed of both judges and citizens and charged with enforcing the Texas Code of Judicial Conduct promulgated by the Texas Supreme Court, began an investigation of Hensley’s actions. In 2019, the Commission issued Hensley a public warning, stating that her actions violated Canon 4A(1) of the Code, requiring a judge to “conduct all of the judge’s extrajudicial activities so that they do not … cast reasonable doubt on the judge’s capacity to act impartially as a judge.”

In response to the warning, Hensley again stopped performing any marriages but also filed a state court lawsuit challenging it. At essentially the same time, Jack County Texas Judge Brian Umphress filed a separate federal lawsuit challenging the Commission’s interpretation of Canon 4A(1), claiming that he, too, had the right to refuse to marry same-sex couples based on religious reasons.

After years of litigation of Hensley’s state court lawsuit, the Commission in October 2024 rescinded its warning to Hensley. Meanwhile, in April 2025, the Fifth Circuit Federal Court of Appeal in Umphress’ litigation asked the Texas Supreme Court to explain whether Canon 4A(1) “prohibit[s] judges from publicly refusing, for moral or religious reasons, to perform same-sex weddings while continuing to perform opposite-sex weddings.”

The Texas Supreme Court then, in late October 2025, added a comment to Canon 4, stating that a judge’s “publicly refrain[ing] from performing a wedding ceremony based upon a sincerely held religious belief” did, in fact, not violate the Code. But the Commission on Judicial Conduct in a December 2025 lower court filing in the ongoing Hensley state court litigation asserted that the Supreme Court’s comment did not explicitly answer the question whether a judge could refuse to marry same-sex couples, while still performing different-sex weddings. It explained that the comment “only gives a judge the authority to ‘opt out’ of officiating due to a sincere religious belief, but does not say that a judge can, at the same time, welcome to her chambers heterosexual couples for whom she willingly offers to conduct marriage ceremonies.”

With her state court litigation still pending, Hensley in late December filed the new federal lawsuit, seeking to be able to use her religious beliefs to justify refusing to marry LGBTIQ+ couples, while still marrying heterosexual couples. The federal courts should flatly reject her case. The U.S. Supreme Court was unambiguous in Obergefell and the subsequent Pavan case: “the Constitution entitles same-sex couples to civil marriage ‘on the same terms and conditions as opposite-sex couples.’”

Any other outcome would not only undermine same-sex couple’s dignity and equality, but also as a practical matter could create substantial impediments to same-sex couples being able to marry in some geographical areas. Even if a county issued a same-sex couple a marriage license, every eligible government official in the county could use religion as a basis for refusing to conduct a wedding ceremony for the same-sex couple. Finding a qualified and willing private officiant could prove extremely difficult, too, because no private officiant can be forced to marry a couple they do not want to.

Moreover, chaos would reign if judges—elected or appointed to serve all citizens—were permitted to use their religious beliefs as a basis to refuse to marry particular couples. Those beliefs could include refusals based on race, national origin, religious belief or identity, or political affiliation, just to name a few. Indeed, the lower court judge in the landmark Loving v. Virginia case, establishing the constitutional right of interracial couples to marry, justified his upholding Virginia’s ban on such marriages on his religious beliefs. He stated: “Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay, and red, and he placed them on separate continents … [and] did not intend for the races to mix.”

The ultra-conservative supermajority of the U.S. Supreme Court in recent years has established religious exceptions to exempt some private parties from particular anti-LGBTIQ+ discrimination laws. It has expanded such religious exceptions in other contexts as well. But broadening these exceptions to include state court judges would be a dangerous expansion that we hope even this Court would resist.

So far, no same-sex couple has been denied the right to marry since Obergefell, and marriage equality retains broad public support nationwide. Together as a nation, we must ensure that remains the case.

We’ll continue to report on significant developments in the ongoing Texas litigation as it unfolds.

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making samesex marriage legal nationwide.

6/26 and Beyond

Published on July 15, 2026

Recent Comments