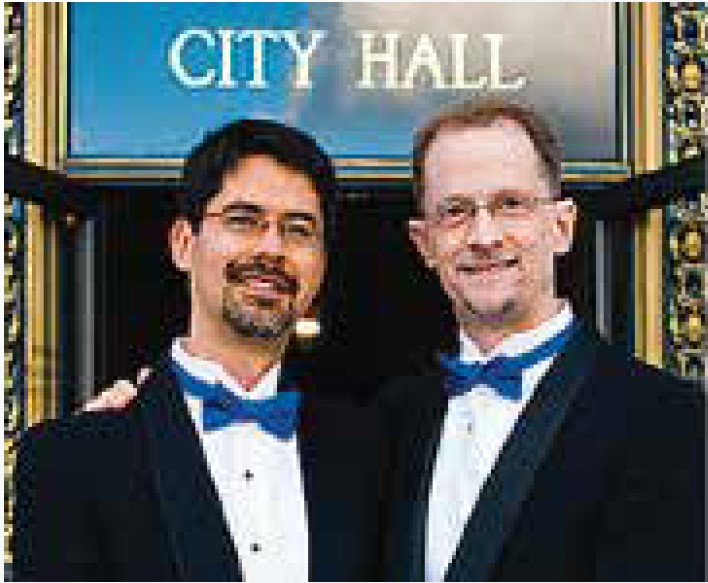

By Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis–

Greetings from Munich! We’re here to attend the 25th International AIDS Conference, which brings together an estimated 15,000 participants from all around the world to exchange the latest information, best practices, and lessons learned over the past 40 years of the pandemic. This year’s conference seeks to coalesce around a “unified and equitable response” to HIV/AIDS, grounded in “an evidence-based approach” that first and foremost “puts people first.”

Munich is a fitting place for the conference as a diverse international city with a thriving LGBTIQ community. Bavaria has a long, deep, and sometimes difficult queer history dating back centuries. In the second half of the 19th century, it was home to the famous gay Hapsburg monarch, Ludwig II, best known for his creation of architectural jewels such as the magical Neuschwanstein Castle, the inspiration for modern-day Disney’s Sleeping Beauty castle, and his passionate personal infatuation with and patronage of the great romantic composer Richard Wagner. Sadly, Ludwig II met a tragic end at age 22 under mysterious circumstances that continue to invite speculation nearly 140 years later. And undoubtedly, he suffered enormously as a gay Catholic king who had to repress his sexuality.

But Munich is also where Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, considered by some to be “first gay man in world history,” became the first openly gay person to advocate publicly for gay rights when, in 1867, he gave a speech urging the Congress of German Jurists to support a repeal of the state’s anti-gay laws. The themes Ulrichs sounded still resonate today. In a pamphlet he published about his speech, he referenced how societal homophobia had deprived gay people of their happiness and led some to suicide. Ulrichs proclaimed:

“Until my dying day I will look back with pride that I found the courage to come face to face in battle against the specter which for time immemorial has been injecting poison into me and into men of my nature.”

Thirty years later, Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld and other gay rights pioneers in 1897 founded what is considered the first LGBTIQ rights advocacy organization in the world, the dryly named Wissenschaftlich-humanitares Komitee or Scientific Humanitarian Committee (SHC). The mission of this broad-based organization, whose membership included physicians, academics, attorneys, and activists, was to repeal the notorious Paragraph 175 of German legal code (adopted in 1871 from Prussian law) that criminalized same-sex sexual activity.

Until the Nazis came to power in 1933, queer life in Berlin and some other places flourished within constraints with little if any enforcement of Paragraph 175. Gay artists, such as Helmut Kolle and Max Oppenheimer, emerged. The Nazis confiscated works of both artists as “Degenerate Art.”

During the Nazi reign of terror from 1933 to 1945, approximately 100,000 gay men were arrested for being gay, with half of them sentenced to prison, and up to 15,000 were sent to the concentration camps, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

One of the first concentration camps that imprisoned gay men was Dachau, located not far from Munich in Bavaria. In the camps, gay men faced ostracism at the hands of fellow nongay prisoners, exceptionally burdensome work details, and other abuse, including castration for some. It is estimated that approximately half of the gay men sent to the concentration camps died. Over the course of World War II, approximately 800 gay men from Germany and Austria were sent to Dachau, with just over 100 documented deaths.

But today, we see the fruits of decades and decades of LGBTIQ people standing up for themselves and carrying forward the mission to which Ulrichs first gave public voice over 150 years ago. The artwork of Kolle and Oppenheimer and numerous openly queer artists is now displayed in galleries in Munich, Vienna, and across Europe. Before coming to Munich, we attended the opening of EuroGames 2024, where thousands of LGBTIQ athletes from over 40 countries around the world came together for numerous sporting events. The games, which began in 1992, offer queer athletes of all different abilities the opportunity to build community by playing sports together in a completely safe space.

The opening ceremonies featured performances by Vienna’s dynamic Schmusechor (Kissing Choir) and the fabulous Conchita Wurst, who in 2014 became overnight a queer superstar when she won the coveted Eurovision song contest. Accepting the award, Wurst, who is also openly HIV-positive, told the over 180 million viewers that she dedicated it “to everyone who believes in a future of peace and freedom,” reminding viewers: “You know who we are—we are a community, and we are unstoppable.” She repeated those words to the crowd last week at the Eurogames.

Earlier this afternoon, we walked by an old Nazi-era building in Munich, and instead of a swastika flying in front of it, we saw a large Rainbow Flag blowing brightly in the wind as it now appears to do all the time. Ulrichs would have been proud and gratified that Munich, where he gave his prophetic speech, is hosting the 25th International AIDS Conference, bringing hope to millions around the world.

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

626 and Beyond

Published on July 25, 2024

Recent Comments