In 1953, when he was only 29 years old, James Baldwin published Go Tell It on the Mountain, his first novel. The semi-autobiographical story of growing up in a deeply difficult world of poverty, institutional racism, and adolescent homosexual awakening made him world famous. The work was so personal because Baldwin believed, “One writes out of one thing only—one’s own experience.” When, years later, a television interviewer asked him to describe the challenges he had encountered at the beginning of his career as “a black, impoverished homosexual,” Baldwin simply laughed and replied, “I thought I’d hit the jackpot.”

In 1953, when he was only 29 years old, James Baldwin published Go Tell It on the Mountain, his first novel. The semi-autobiographical story of growing up in a deeply difficult world of poverty, institutional racism, and adolescent homosexual awakening made him world famous. The work was so personal because Baldwin believed, “One writes out of one thing only—one’s own experience.” When, years later, a television interviewer asked him to describe the challenges he had encountered at the beginning of his career as “a black, impoverished homosexual,” Baldwin simply laughed and replied, “I thought I’d hit the jackpot.”

Having grown up black, poor, and gay in a predominantly white, sexist, and racially biased United States, Baldwin, sadly, felt he could write the book not in Harlem, the community where he grew up and the novel’s setting, but only in Europe. He moved there in 1948, soon after walking into a restaurant where the waitress explained that black people were not served. Thoroughly disenchanted by American prejudice against minorities, he remained abroad until 1957.

After the book became a great critical and popular success, many labeled him the new “Negro novelist.” Baldwin, however, refused to be categorized. “Human beings,” he stated, “cannot ever be labeled.” Labels, he believed, not only simplified and compromised our complex individuality, but forced us into hurtful categories. “People refuse,” he explained, “to function in so neat and one dimensional a fashion.”

To avoid being typed as an author, Baldwin’s second novel, Giovanni’s Room, published in 1956, said nothing about “the Negro experience,” or any other experience, in the United States. The love story of a white man living in Paris who cannot decide between two lovers—one a woman, the other a man—it included a candid description of a same-sex love affair. No major American publisher would accept the manuscript until Baldwin, who would not be dissuaded by his agent, found a publisher in Great Britain.

Baldwin, who was open about his sexual orientation, also rejected sexual labels and definitions. He believed that love was love, consummate, boundless, and gender blind. “Those terms, homosexual, bisexual, heterosexual,” he said,” are 20th-Century terms which, for me, really have very little meaning.” They led first to cultural stereotypes and then, worse, to the belief by individuals that there was something wrong with them when they could not live up to idealized expectations. “You have to decide who you are and force the world to deal with you, not with its idea of you.”

Beginning in 1949 with “The Preservation of Innocence,” an essay published in Zero, a Moroccan journal, Baldwin affirmed homosexual desire as natural and legitimate. He argued that homophobia was a result of sexism, which claimed that men were naturally superior to women and so gave them “sexual supremacy” to direct political, social, economic, and domestic life. The sexists, he wrote, reviled homosexual men because, in the mythology of homophobia, they were imitation women. Their assumed effeminacy challenged domestic femininity as well as staunch masculinity, and, like women, they were inferior because they were not “men,” because their sexuality was not male. The article did not appear in print in the United States until 1989.

Baldwin denounced racism, sexism, and homophobia his entire life. “Whether or not homosexuality is natural seems to me completely pointless,” he wrote, “pointless because I really do not see what difference the answer makes. It seems clear, in any case, at least in the world we know, that no matter what encyclopedias of physiological and scientific knowledge are brought to bear the answer never can be yes. And one of the reasons for this is that it would rob the normal—who are simply the many—of their very necessary sense of security and order.” Although he returned to the United States in 1957 to become active in the civil rights movement, he would live in France for most of his later life.

Baldwin explored the interconnections between sexual insecurities and racial hostilities across his career, from Another Country, published in 1962, to The Evidence of Things Not Seen, published two years before he died in 1987. He not only concerned himself with the experiences of blacks in American society, but also with the entire web of beliefs, prejudices, and justifications that pained relations between the races—and with the ways that gender interactions and sexual relations often blocked reconciliation, forgiveness, and love.

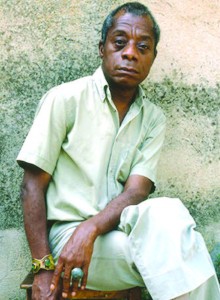

With no reason to believe that he could ever leave destitution, Baldwin, born in 1924, triumphed over every disadvantage to become one of the greatest, most insightful, and eloquent of American humanists. In his writings—novels, essays, plays, poetry, and social commentary—he continuously explored the presence of racial, sexual, gender, class, and identity bias in Western cultures, and their impact on individual lives. The insight and passion of his thoughts and words, which made him such a vital advocate for racial equality and human rights during his lifetime, will endure to make him a champion of humanity for all time.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

David Perry oversees the Rainbow Honor Walk series. He is co-founder and co-chair of the nonprofit Rainbow Honor Walk, which has created a landmark memorial in the Castro to heroes and heroines of the LGBT community. He is also the CEO and Founder of David Perry & Associates,

David Perry oversees the Rainbow Honor Walk series. He is co-founder and co-chair of the nonprofit Rainbow Honor Walk, which has created a landmark memorial in the Castro to heroes and heroines of the LGBT community. He is also the CEO and Founder of David Perry & Associates,

http://www.davidperry.com/

Recent Comments