Rodney Barnette made history in 1990 when he became the first Black individual to own a gay bar in San Francisco: The New Eagle Creek Saloon. As the founder of the Compton, CA, chapter of the Black Panther Party and as an out gay man, Barnette desired to create a safe space for the Bay Area’s multiracial queer community who were marginalized in other social spaces throughout the city.

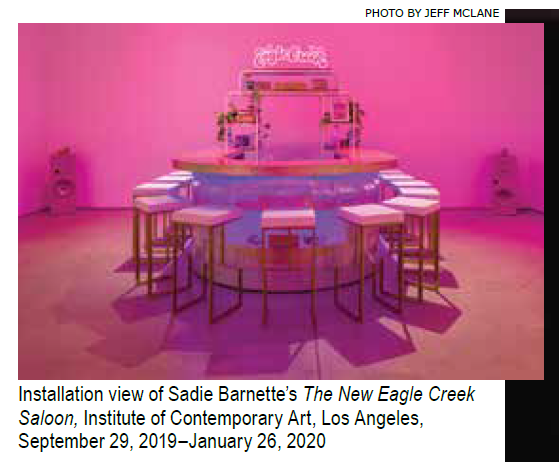

A new exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), Sadie Barnette’s The New Eagle Creek Saloon, on display from April 22–May 11, 2023, reimagines the groundbreaking establishment. Sadie, Barnette’s daughter, based in Oakland, not only reminds us of The New Eagle Creek Saloon’s historical and ongoing importance, but also evidences her own skills as an artist exploring Black life, personal histories, and sociopolitical issues.

The San Francisco Bay Times recently learned more about The New Eagle Creek Saloon and the related exhibit from Sadie, Tomoko Kanamitsu, Marin Sarvé-Tarr, and Jenny Gheith. Kanamitsu is the Barbara and Stephan Vermut Director of Public Engagement at SFMOMA. Sarvé-Tarr and Gheith are both assistant curators of painting and sculpture at the museum.

San Francisco Bay Times; It is remarkable to consider that The New Eagle Creek Saloon was the first Black-owned bar for the gay community in San Francisco. Did Rodney Barnette own any other establishments previously or at the time?

Sadie Barnette: He had never owned a bar before. He worked as a bartender for 6 months to learn the business before taking over as owner.

San Francisco Bay Times: We loved hearing, from those who were there, what opening night was like at The New Eagle Creek Saloon. Apparently, music from Prince and Grace Jones were on the playlist. Does the SFMOMA exhibit capture some of this authentic vibe, or is it more reflective of current music and times?

Tomoko Kanamitsu: The SFMOMA presentation both pays homage to and expands upon the original New Eagle Creek Saloon. The opening public program, “A Friendly Place: The History of The New Eagle Creek Saloon,” will feature Rodney Barnette and Sadie Barnette, as well as former patrons of the bar such as Stephen Dorsey. The DJ from the original bar, BLACK, will be the guest DJ for the evening and they will discuss the history and legacy of the bar itself.

As for the installation, while not much remains of the original bar, the mirrors installed on the back wall are from the original location and many elements of the bar are scattered throughout. A zine featuring ephemera from the bar and clippings from The Bay Area Reporter newspaper, and photographs of patrons past and of Rodney Barnette with family will be available for visitors to flip through. Further public programming and the bar itself will be activated with dance parties, music, performances, and film, and, of course, drinks. [All will] create a space to create intergenerational connections, to mourn, and also celebrate with and for queer communities of color, past and present.

San Francisco Bay Times: The Bay Times, founded in the 1970s, also mentioned The New Eagle Creek Saloon in its pages back in the day. Some of our present team, including our lead photographer Rink, remember their visits to the Saloon. Even those who were not present can see that the SFMOMA installation created by Sadie Barnette is incredibly dynamic. Is there any other artistic work like it that you can think of, where visitors can experience some sense of an actual past venue but within a sort of fantasy framework created by the artist?

Tomoko Kanamitsu: [Two that come to mind are] Rirkrit Tiravanija, Apartment 21 (Tomorrow Can Shut Up and Go Away), 2002 (https://tinyurl.com/2w6pj7py ) and Wu Tsang, WILDNESS, 2012, at SFMOMA.

San Francisco Bay Times: Please share your own thoughts about The New Eagle Creek Saloon installation. What do you think is most unique about it? What resonates the most with you?

Tomoko Kanamitsu: This installation is unique because it functions as an operating bar, requiring a liquor license and other logistical details. It’s also not only about the objects and ephemera but the public programs curated by Sadie Barnette in collaboration with the museum that activate the bar and bring it to life. It will also be a transformational experience for visitors, to walk into a gallery in the middle of the day that is an artwork, bar and nightclub, where time has shifted, to dance, chat, meet friends and strangers, and reflect on the legacies and futures of queer multiracial spaces in the neon pink glow of Barnette’s installation.

Also, there are five unique public programs and happy hours for enjoying a drink; we hope visitors will return more than once to experience this unique artwork.

Marin Sarvé-Tarr and Jenny Gheith: Like much of Barnette’s work, this installation and performance series mines the artist’s family history to reanimate the past. She brings photographs and moments from the past to the present by inserting her own visual language of images, text, and sparkly glitter. What is so special about hosting her New Eagle Creek Saloon at SFMOMA is the ways it brings her father’s story and this important local San Francisco history to life in a new way each time the installation is activated.

San Francisco Bay Times: Sadie Barnette has said that all art is political, whether intentional or not. What do you think is the political meaning of the installation?

Tomoko Kanamitsu: While I can’t speak for Sadie, in the past fifteen years many iconic queer bars have closed in San Francisco including The Stud, Virgil’s Sea Room, Beatbox, Marlena’s, Kok, the Deco Lounge, the Gangway, the Old Crow, and the Lexington Club. The pandemic exacerbated the closures. While there are some glimmers of a resurgence—such as the recently opened Mother Bar at the former Esta Noche—the installation connects to the city’s legacy of community spaces for queer people of color and creates resonances between the AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics, which disproportionally affect people of color.

Marin Sarvé-Tarr and Jenny Gheith: Barnette’s work so often draws from moments where personal histories and everyday lived moments like birthday parties and family celebrations overlap with broader social histories. By weaving together these narratives, her work celebrates little known shared acts of celebration and resistance that are drivers behind political moments.

San Francisco Bay Times: Is it known why The New Eagle Creek Saloon had to close after just three years?

Sadie Barnette: The overhead was very high, and when a financial recession hit, it was no longer feasible to keep it going.

San Francisco Bay Times: For us there is a bittersweet aspect to the exhibit, given that there aren’t many Black owned establishments for today’s LGBTQ+ community in San Francisco. Do you think that a place like The New Eagle Creek Saloon could succeed now, or was it such a phenomenon of its particular place and time?

Tomoko Kanamitsu: I think it’s important for there to be spaces like The New Eagle Creek Saloon today and into the future. The current economic environment for food and beverage businesses in the San Francisco Bay Area is incredibly challenging, of course. One of the installation’s main collaborators is the Oakland bottle shop, Alkali Rye, which prioritizes products made by BIPOC, women, and queer people, and produced by sustainable methods. It is hosting all the museum’s happy hours and public programs. In the best possible scenario, people—especially, but not limited to, young people—visiting the installation will be inspired to become artists and entrepreneurs that can imagine more Black-owned spaces and businesses.

San Francisco Bay Times: We are curious what Rodney Burnette thinks of the exhibit.

Sadie Barnette: He is thrilled that I am telling the story of The New Eagle Creek Saloon and that he gets to be an active part of telling the tales and history. Many folks who used to frequent his bar have been able to participate in my project and they are all eager to talk about what the bar meant to them, and to make sure the name is not lost to history. He always wanted to have some kind of reunion but never imagined it would be an art exhibition that traveled the country.

As Sadie indicates, see the exhibit before it moves on! The related special interactive events—weaving libations with music, dance, and more—will likely have visitors coming again and again, just as they did in the early 1990s at The New Eagle Creek Saloon on Market Street.

Published on April 20, 2023

Recent Comments