By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney–

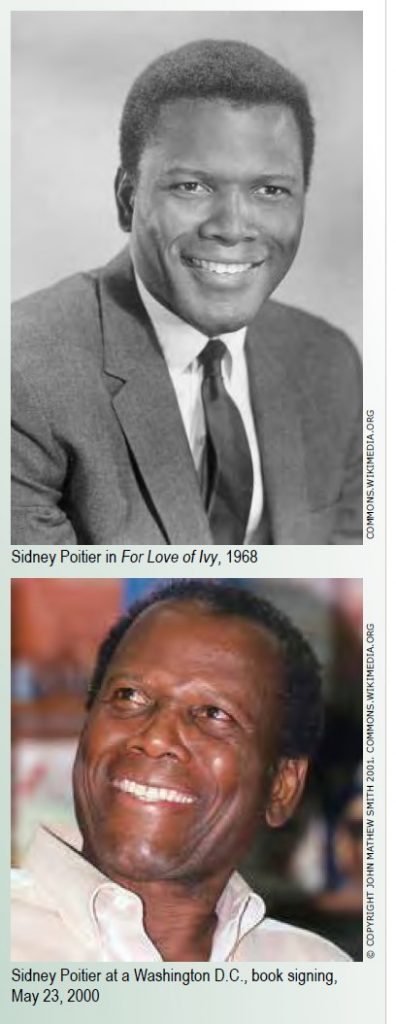

When legendary actor and civil rights pioneer Sidney Poitier died earlier this month, we were struck to learn that Poitier credited the dignity he felt as a person of African descent growing up in the Bahamas as the foundation for his natural ease in portraying powerful, confident, and unapologetic African Americans on the big screen with incomparable eloquence and intelligence. Poitier explained: “I never had an occasion to question color; therefore, I only saw myself as what I was … a human being.”

Poitier’s insight about the sources of his personal confidence sheds light on the pernicious effects that legal and societal systems of discrimination have not only in specific substantive areas like employment, housing, and education, but also on the psyche of those oppressed or marginalized.

When Poitier came to the U.S. as a teenager in 1942 to live with his brother in Miami, he experienced very different attitudes than he had in his formative years in the Bahamas. As Poitier told NPR in 2009, he “couldn’t adjust to the racism in Florida,” because it was “so blatant.” He explained: “I had never in my life, my early life, been so described as Florida described me.” He interpreted Florida as saying to him that “you are not who you think you are. We will determine what you are.” In face of such insult, Poitier resolved: “No, I will determine who I am.”

Poitier decided to leave Florida and move to New York City, where he pursued an acting career. Throughout that storied career, he never wavered in that commitment to his dignity and embodied it in his numerous groundbreaking portrayals of African American characters, most iconically the fearless Virgil Tibbs in In the Heat of the Night. As historian and Black studies professor Elwood Watson put it, “Poitier skillfully showcased the dignity and pride of the Black experience to the entire world.”

Although Poitier did not directly address LGBTIQ issues in his work, the actor’s life, in particular his steadfast commitment to never compromising his integrity, served as a model for LGBTIQ people and indeed for all those who face discrimination and adversity. LGBTIQ people, like other marginalized minorities, deserve to live in a society that does not cause us to question who we are or our worthiness or to impose upon us its determination of who we are. Dignity and pride lie at the heart of the LGBTIQ movement.

Poitier’s discernment that white Floridians in the 1940s believed they possessed the power and entitlement to determine who he was as a Black person reminds us of the presumptuous attitudes of a prominent homophobic Floridian decades later—Anita Bryant, leader of the anti-gay “Save Our Children” campaign of the 1970s.

Several years ago during the height of the marriage equality movement, we rewatched Poitier’s classic film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. We, of course, appreciated the audacious statement the movie was making about race and love in 1967, the same year the U.S. Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia ruled that laws banning interracial couples from marriage were unconstitutional.

The film also spoke to us across the decades as an LGBTIQ couple working as part of the movement to end discrimination against LGBTIQ people in marriage and all other aspects of our lives. Indeed, every time LGBTIQ people come out to their parents or introduce their partners to their families not knowing what will ensue, they play out their own real-life versions of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. In the face of uncertainty and challenge, LGBTIQ people have needed to summon the same inner strength, commitment to ourselves and each other, and willingness to fight for our love that Poitier’s character and his fiancée display in the movie.

At the end of the film, the white father portrayed by Spencer Tracy, who has been reluctant to accept the marriage, recognizes that the young couple’s love is no different than his own love for his wife. He proclaims that “in the final analysis it doesn’t matter a damn what we think. The only thing that matters is what they feel.” In the face of bigotry, the father advises, “where necessary, you’ll just have to cling tight to each other and say screw all those people,” declaring “there would be only one thing worse” than the adversity they will face getting married and that is if they “didn’t get married.” Tracy’s character could have been speaking to LGBTIQ couples in 2015, the year the U.S. Supreme Court held that prohibiting same-sex couples from marrying violated the Constitution.

Poitier enunciated in his autobiography: “I am the me I choose to be.” May that dictum be true for all of us in all aspects of our lives.

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Published on January 27, 2022

Recent Comments