By Jewelle Gomez–

On the topic of lesbian artists/change makers I’ve known, Fortune has graced me with a wildly diverse list. Celebrating their passage is an enriching privilege that we can all share.

Nikki Giovanni

One of the first writers I met when I moved to New York City in 1971 was Nikki Giovanni (1943–2024), who was originally from Tennessee. A mutual friend introduced us because Nikki was looking for a babysitter for her son. She was already a voice for the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, reading poetry on the TV show Soul and on programs with Black revolutionary writers like Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez.

When I’d arrive at her high-rise apartment, there’d be no time for chatting; she was always rushing. But my impression: this is one of the most dynamic balls of energy I’ve ever met. She was petite, moved briskly, and had a musical voice whether she was reading her poems, delivering a college lecture, or asking me to stay later than we’d agreed. On her way out, she’d often toss me a book she received, asking if I’d read it. And, once alone, I’d read intently as if she were going to test me when she got home. She wasn’t. She just liked to share the good word because she was a preacher for liberation.

With her rhythmic, lyrical delivery of her work, Nikki was hip hop before it had a name. She used her gifts to call the Black community and women to attention, reminding us of what the dominant culture wanted us to forget: we are purposeful and strong. Even her children’s books were equally clarion calls to embrace personal strength. Being at her readings was like attending a concert or Baptist church—the cheers and amens overshadowed anything elicited by Taylor Swift.

A line from one of her paeans to Black women, “Ego Tripping,” has stayed with me for more than 40 years and works really well to redirect rage engendered by disasters like bad election results. I believe most lesbian/feminist artists are trying to give us personal mantras like this to help us survive and thrive: “I am so perfect so divine so ethereal so surreal/I cannot be comprehended except by my permission … .”

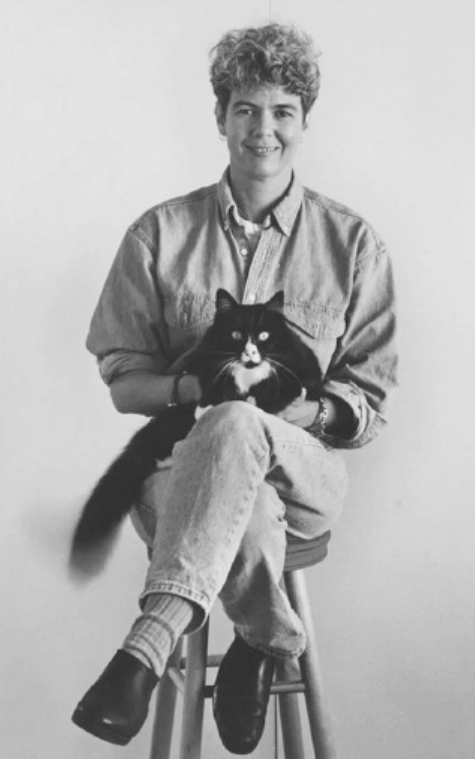

Cathy Cade

Cathy Cade’s (1942–2024) mantra is evidenced in the introduction to her now classic book A Lesbian Photo Album: The Lives of Seven Lesbian Feminists. She acknowledges that the process of creating the book, published in 1987, stalled until she felt strong enough to do the necessary outreach so the book wasn’t all white women.

The importance of the word “strong” echoes the messages in Nikki Giovanni’s poems. Embracing our strength will help us do, not the easy thing, but the right thing. When I met Cathy in the early 1990s, I thanked her for thinking about the strength it takes for women to change things—from political institutions to social mindsets. The snapshots that Cathy assembled of a lesbian world were like a vitamin boost to me and other “Baby Boomer” lesbians whose lives were characterized by invisibility. A photo of an African American lesbian dancing with her two cats, of a white lesbian proud of her baseball mitt, of a fat bare-breasted lesbian with a seductive smile, were what brought us each into focus for ourselves.

Cathy’s strength served her well over the decades of her activist/ photography career beginning in the 1970s after working with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee as part of the Civil Rights Movement in the South. She and JEB (Joan E. Biren) were the primary lesbian photographers documenting the political activism of the 1970s and ‘80s, and fortunately both of them were unrelenting in their ability to document what lesbians were doing with our lives.

Cathy, born in Hawai’i, and the mother of two sons, had a lifelong engagement with social activism including her involvement with Old Lesbians Organizing for Change here in the Bay Area. Her focus on the ordinary lives of lesbian feminists as artists, parents, and activists was a perennial celebration—as was she, as she was upbeat, energetic, and always with an idea for a new project. Her work is collected at the University of California, Berkeley, Library where we can be reminded of what a nascent revolution looks like.

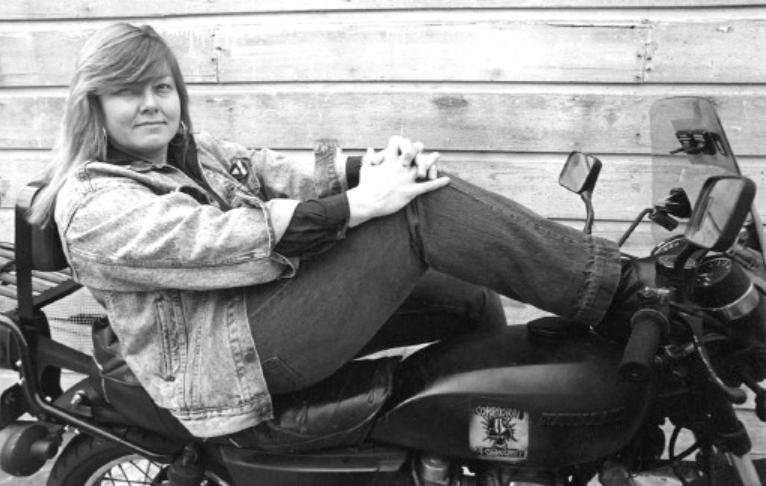

Mary Wings

Another voice of our community, novelist and cartoonist Mary Wings (1949–2024), surprised me with a call, soon after I moved to the Bay Area in 1993, to invite me to have coffee. An avid reader of mysteries, I loved her series featuring lesbian detective Emma Victor (along with Randye Lordon’s Sydney Sloan series), so I tried not to fan girl as I sat down to my first coffee date in San Francisco. Once seated with our lattes, Mary told me she was writing a new Emma Victor mystery and one of the suspects in the murder case was … kind of based on me! She referenced a public fundraising event I’d done; she had me and my chiropractor partner painted perfectly down to the snappy little two-seater convertible I drove.

I was honored and not surprised at how precise She Came by the Book was. Mary, originally from Chicago, had an uncanny way of seeing around the corner of how people presented themselves. She also possessed a wicked sense of humor, an irreverent relationship to rules, and an eclectic collection of interests from publishing the first lesbian comic book to playing the banjo and accordion. When I attended Mary’s memorial/block party, it was clear that her neighbors loved how she embraced all things quirky. In elegant script above the front door of her house was written, “This House Protects the Dreamer,’ a quote each of us might benefit from seeing every time we come home.

Dorothy Allison

In 1981, before moving to the Bay Area I was invited along with several other writers, to join the Conditions magazine collective. The first meeting for newbies was held in the Brooklyn flat of Dorothy Allison (1949–2024). Crossing into the living room I passed through a clanking curtain of chain links and thought, “This is going to be some meeting!” I was sitting in the living room of a white southerner for the first time in my Yankee life; her hair was flaming red/orange and she was a poster child for BDSM before most folks knew what the initials stood for.

At that time, Dorothy was mostly writing poetry. Once we each overcame our mutual fear of what the other symbolized, we became fast friends; as close as two high femme peas in a pod. We exchanged our writing as if we’d known and trusted each other all our lives. Her feedback helped shape my recent play about James Baldwin. But, thank goodness, we didn’t always listen to each other, or her first collection of poetry, The Women Who Hate Me, would have had a really sappy title.

Born in South Carolina, Dorothy lived in Florida for several years before moving to New York City where she worked a number of blue-collar jobs, helped found the Lesbian Sex Mafia, and developed a strong class analysis along with her feminism. We were both published by the lesbian, feminist press Firebrand Books in our early years, which deepened our bond that endured as we both crossed the country to live in the Bay Area.

Here she settled down to marry her girlfriend and raise their son. Reading her largely autobiographical novel, Bastard Out of Carolina, clarifies what strength Dorothy used to overcome her past and find joy, The book is a searing tale of a young girl’s sexual and emotional abuse in a poor, white, southern family. It’s also about triumph, which made it the cornerstone of the movement to support women and girls who’ve been victimized.

Dorothy’s book was the seed out of which the MeToo Movement and the rallying cry “Believe Women” grew.

As we start to pass on, it is valuable to remember that Baby Boomers were the generation that brought social change movements to campuses and factories, to the Pentagon, to wives’ kitchens, children’s daycare centers, and to the streets. Each of these lesbian artists/activists has left an amazing legacy that offers signposts to change for the next generations. It’s hard for me to imagine this planet without these warrior artists. But as long as their work is available to read, to see, discuss, and teach, these divine women are never lost to us.

Jewelle Gomez is a lesbian/feminist activist, novelist, poet, and playwright. She’s written for “The Advocate,” “Ms. Magazine,” “Black Scholar,” “The San Francisco Chronicle,” “The New York Times,” and “The Village Voice.” Follow her on Instagram and Twitter @VampyreVamp

Leave Signs

Published on December 19, 2024

Recent Comments