By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

In a city with more queens than a playing cards factory, San Francisco’s celebration of All Hallow’s Eve was once the night of nights. With so many grand events in so many bars from the Embarcadero to North Beach to Polk Street, being seen at even the ones that mattered most was a daunting task. Cinderella’s fairy godmother may have turned a pumpkin into a coach fit for a princess, but no fairy can turn a Muni bus into a transport fit for a queen.

Beginning in the 1950s, the most glamorous drag queens, who spent weeks and weeks creating their fabulous ensembles, traveled from one festivity to another with tuxedoed escorts in rented limousines. Arriving in grand style, they made their grand entrance into the Hideaway in the Tenderloin, the Talk of the Town on Lower Market Street, the Jumpin’ Frog in Polk Gulch, Jack’s Waterfront on the Embarcadero, and especially the Black Cat Café in North Beach, where the great José Sarria, the Nightingale of Montgomery Street, regularly performed for his adoring followers.

José was the true fairy godmother of the evening. As the journalist and historian Randy Shilts described it, on Halloween the Chief of Police himself drove him “to the center of North Beach … opening the car door politely for the elegantly gowned drag queen” and reminding him, “‘This is your night—you run it.’ For that one night, the police let homosexuals roam the city freely, even if they wore dresses … . But when the hours shifted from October 31 to November 1, the iron fist of Lilly Law would fall again.”

At any time, but especially on Halloween, the police could stop, question, and arrest whomever they claimed was violating Section 440 of the San Francisco Municipal Penal Code, which made it illegal for men to dress as women in public, supposedly to protect the naive or gullible from being misled or swindled for illicit or lustful purposes. It gave them all the reason they needed to harass and jail tastefully costumed gays as they left bars and parties on their way home.

José hoped to protect those who did not travel in limousines and who had badges that stated, “I am a boy.” Now all anybody stopped by the police had to do was explain, “The law states it is unlawful to dress with an intent to deceive, but I am stating my gender plainly.” The police may not have liked it, but they understood their legal risk from arresting someone—even a gay man— whom they knew was not guilty. The ordinance finally was declared unconstitutional in 1961.

By then revelers were renting motorcoaches to take them on their appointed rounds. Not only could they carry a movable festival, so the party never stopped, but they also provided a safe space, away from prying eyes, where merrymakers could make necessary repairs before facing the crowds in front of the bars. After all, taffeta crushes so easily. Heels snap so unexpectedly. Makeup smudges and smears so awkwardly. They assured a last-minute perfection before entering any gala where awards would be given for the best gay apparel.

No one remembers who rented the first bus. One of the earliest in 1961, which did a grand circuit of five bars, belonged to “Michelle and the Hollywood Starlets.” Michelle, a hugely popular drag performer and one of Jose’s affectionate rivals—they were “friendly competitors,” he told JD Doyle in an interview for Queer Music Heritage in 2012, and “very, very dear friends”—opened Bill’s Beauty Land at 587 Castro around 1958, the first openly gay-owned business in the neighborhood, and appeared regularly in cabarets and revues.

From the H’Burners Bus in 1962, cited for having “such elegance, such costumery, such impersonation,” to the “Bette Davis on Canvas” bus in 1976, the rented motorcoaches were a Halloween tradition for almost two decades. Eventually there were so many of them that they had to run on a schedule. The number of bars and clubs that welcomed them also grew, offering trophies or cash prizes for best costume or “best male” and “best female,” best couple, best group, and, of course, best bus.

Immense crowds of spectators also became part of Halloween. In 1962, according to the L.C.E. News, they outnumbered the party goers at some of the bars. In front of the Black Cat, “the traditional spot for Halloween big times,” somewhere “between five and seven or eight thousand people,” who had “come down to the Cat to see what the styles are going to be next year,” blocked the sidewalk. The paper speculated that the gay community “made up probably less than 10% of the onlookers.”

It was not much better in other parts of the city that year. The D’Oak Room at 350 Divisadero “was packed to the posters.” Trying to celebrate at the Barrel House at 88 Embarcadero “was useless, because you could not get in the doors.” Even with “five persons on the door checking ID,” it was “just this side of bedlam” at Jack’s Waterfront, two blocks away. There were no such problems in the Castro, however. The neighborhood’s first gay bar, the Missouri Mule, had not yet opened.

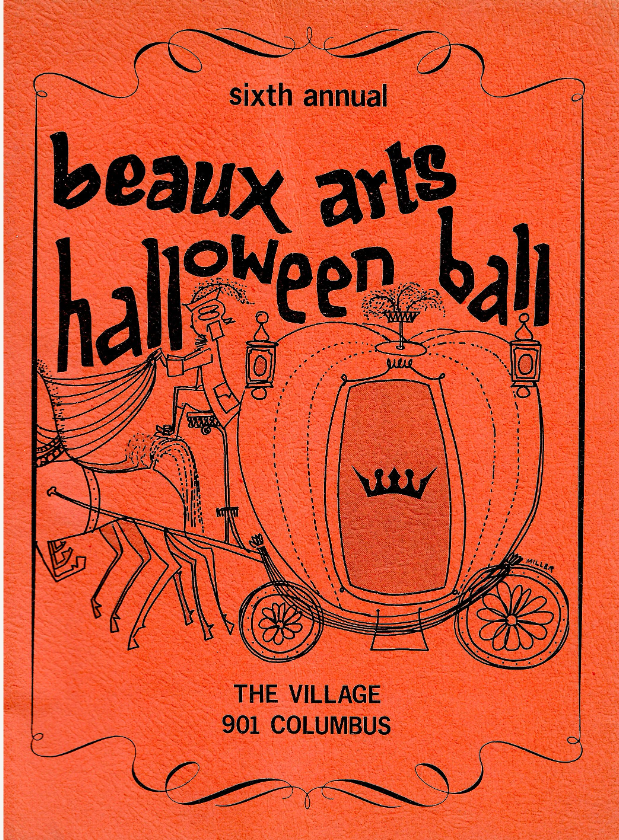

As an alternative to the tumult and the traffic, the Jumpin’ Frog sponsored the original Beaux Arts Ball on Halloween, 1963, but the next year gave up the event to the recently formed Tavern Guild, the first LGBT business association in the United States. In 1964 the Ball was held at the San Francisco Hilton. Some 800 women and men attended. A panel of three ministers—two Methodist and one from the United Churches of Christ—decided the winners of the costume contests.

The Tavern Guild had hoped to honor José at the Ball, but he could not attend. He was there the next year, however, to hear himself proclaimed “Empress Norton I, Camp Queen of these United States and Protectress of Mexico.” According to the December 1965 issue of Town Talk, the “Empress lost no time springing into action—calling ‘her’ first privy council meeting on November 15th, and a second on November 22nd … for the purpose of preparing for a gala coronation ceremony on or about New Year’s, with the ‘royal court’ in attendance.”

For several years, San Francisco chose its empress during the annual Beaux Arts Ball. Although there were other events for every fashion and fetish—from Gold Street’s Halloween Bash to the Galleon’s Witches’ Brunch and Witches’ Buffet—it remained the grand fête of the evening for a long time. Now only fond memories of those long-ago festive celebrations remain. Happily, the Imperial Court—now the Imperial Council—endures, the great, lasting legacy of All Hallows’ Eves past.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on October 19, 2023

Recent Comments