By John Lewis–

The powerful Japanese giants, weighing as much as 350 pounds and clad only in their mawashi (loin cloths), dig their heals into the compressed clay surface of the dohyo (the sumo wrestling ring). These rishiki (literally strong warriors) crouch in fearless and commanding postures, synchronize their breaths as one, and when they both have touched their hands to the ground, lunge forward to engage each other with all the physical strength, as well as mental acumen, they possess. The sumo match has begun.

The titanic rishiki push, tug, slap, and grab at each other’s flesh. Sometimes they find their bodies locked together, faces cheek to cheek, in a forceful and concentrated embrace, as they mightily struggle to gain an advantage. Other times, one wrestler may try to wrap their arm around the other’s lower back to grab the other’s mawashi (sumo waist belt holding up the loin cloth) and flip them to the ground.

The clash of these powerful warriorsis a spectacular display of primal energy incarnate. They seek to call forth the strength of a tsunami to overwhelm their opponent.

But the actual match itself is often very short. It ends as soon as one wrestler forces the other out of the dohyo or when any part of one wrestler’s body other than the soles of their feet touches the ground. That can occur in less than a minute, even mere seconds, depending on how successful one of the wrestlers is at outsmarting their opponent or physically dominating them.

One reason the match itself is designed to be short is that it does not, in fact, stand on its own by itself. It exists only as one component of a much greater ritual, whose meaning dates back millennia. The match is the highlight of an elaborate Shinto-based ceremony that entails many forms and practices and in which all participants play indispensable roles. It’s also one of many matches held on a given day of sumo wrestling. Indeed, on the day of matches that I attended at the Tokyo Nihon Sumo Kyokai (Tokyo Grand Sumo Tournament) recently, almost 70 matches were held.

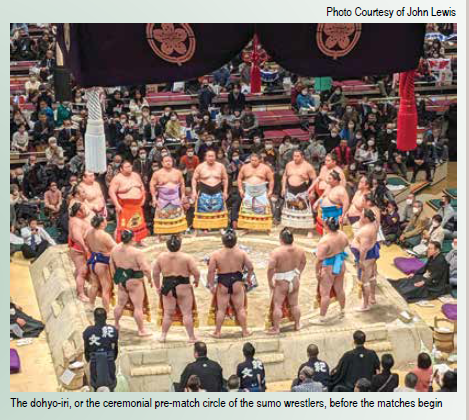

Each series of upper division matches begins with the pageantry of the dohyo-iri in which all the rishiki enter the stage and form a ceremonial circle around the outside of the ring. They are clad in their keshō-mawashi (embroidered full-length aprons extending from their waists), and they raise their arms in an ancient purification act. They then exit the stage as a group to reenter when it’s time for their match.

Yobidashi (attendants) carefully prepare and maintain the dohyo before, during, and after the match. They meticulously sweep the thin layer of sand spread on top of the clay surface of the ring to ensure an even surface. They create beautiful patterns through the graceful movements of their brooms, bringing the same care and attention to their work that Zen monks might give to sweeping the paths in a temple garden. The yobidashi, who is the ring announcer, and is always dressed in colorful traditional clothing, sings the wrestler’s names to call them to the ring in a uniquely stylized manner akin to that of a Kabuki performer. His powerful voice needs no microphone to be heard.

The rishiki themselves engage in elaborate rituals such as raising a leg and then stomping it to the ground to scare off evil spirits. They throw salt into the ring for cleansing every time they enter the ring, and they raise their arms ceremonially when they initially face their opponent to show that they have no hidden weapons. As soon as the match ends, the rishiki assume positions on either side of the dohyo and bow to each other, just before the referee acknowledges the match’s winner. And even as they are still exiting the ring, the yobidashi is calling the next competitors to come forward.

Everything is in perpetual motion. Sumo is believed to have begun in prehistoric times as a devotional dance of hope for a good harvest. It has evolved through numerous eras of Japanese history to its present form that remains vital today.

I like that sumo appears to have begun not as a fight, but as a dance, and that despite the brutality and competitiveness of the match itself, it is part of a ceremonial practice in which all the participants, including the rishiki, exist only as part of a greater whole. Our world needs more dancing together in all the different forms it may take.

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

6/26 and Beyond

Published on January 26, 2023

Recent Comments