Supervisor Rafael Mandelman on February 11 introduced an ordinance requiring the Department of Public Health to update their minimum health and safety standards for commercial adult sex venues and to remove current regulations requiring the monitoring of patrons’ sexual activities and prohibiting the presence of private rooms and closed doors.

Supervisor Rafael Mandelman on February 11 introduced an ordinance requiring the Department of Public Health to update their minimum health and safety standards for commercial adult sex venues and to remove current regulations requiring the monitoring of patrons’ sexual activities and prohibiting the presence of private rooms and closed doors.

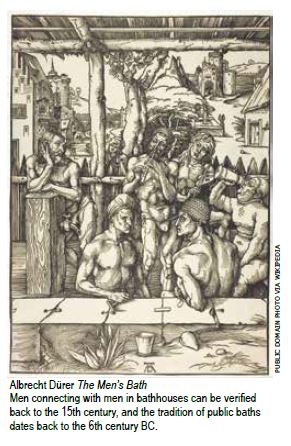

Mandelman wrote: “During the 1970s and early 80s, bathhouses were a focal point of gay social life. They were a place to cruise but were also an important community meeting place where friends would gather to share stories, dance to the latest disco hits, or watch a live show. Performers like Bette Midler and Barry Manilow famously got their starts in the baths. In many ways, bathhouses symbolized the newfound freedom to live out, proud, and happy that gay men from previous generations had never experienced.”

That was all to abruptly change. In 1984, in an attempt to slow the spread of HIV/AIDS, the City of San Francisco filed a lawsuit against the operators of bathhouses, citing them as a public health nuisance. The court concluded that these businesses did present a public health risk, and issued an order allowing the businesses to remain open only if they employed monitors to prevent unsafe sex from occurring and removed most doors to individual video cubicles, booth, or rooms.

Much of this period was chronicled in the pages of the San Francisco Bay Times. Memorably, journalists Michael Helquist and Rick Osmon were asked to research San Francisco’s baths, adult bookstores, theaters, and sex clubs for men at the height of public debate about these establishments. As columnist Dr. Bill Lipsky later wrote: “The Helquist/Osmon investigation was so noteworthy that their work was published—again—nearly two decades later, in the peer-reviewed Journal of Homosexuality (Volume 44, 2003, Issue 3–4).”

Although technically the bathhouses could have remained open under the court-mandated conditions, all of them closed. For many gay men, this marked the end to an era of sexual freedom and further devastated an already reeling community. In 1997, Mandelman shared, the Department of Public Health adopted minimum standards governing the operation of sex clubs and parties. These minimum standards, much like the court order that preceded them, required that all areas of commercial sex clubs, as well as patrons’ sexual activities, be monitored by staff, and prohibited sex clubs and parties from having locking booths, cubicles, or rooms. The minimum standards that are in effect today at places such as EROS include these same restrictions.

“Since the enactment of the minimum standards, queer individuals and community groups have argued that the regulations were invasive, unfair, and unnecessary,” Mandelman said. “Without private rooms, the advocates have argued, people instead have unsafe sex in other venues without safe sex education and supplies.”

As he pointed out, during the time that these regulations have been in place, adult sex venues have continued to operate in San Francisco, providing access to safer sex educational materials and supplies and HIV and STD testing, and in doing so, assisting rather than impeding our efforts to control the transmission of HIV.

He added that the city has also made great strides in Getting to Zero new HIV infections ( https://www.gettingtozerosf.org/ ),

employing an array of new tools to prevent transmission of the virus. “These include the broad availability of PrEP, rapid access to antiretroviral therapy for people newly diagnosed with HIV, and increased viral suppression among people living with HIV through increased retention in care,” he explained. “Given these public health advances, it is time that we align our public health policy with present day science.”

If the ordinance passes, the new minimum health and safety standards governing the operation of commercial adult sex venues would have to be adopted by no later than July 1, 2020—interestingly, putting the momentum at around the time of June Pride. There would, however, be a public notice and public comment process.

Mandelman concluded, “We have consulted with the Department of Public Health extensively in drafting this ordinance, and I would like to thank Director Colfax and Public Health Department Policy Director Israel Nieves-Rivera in particular for their openness to these changes. We have also consulted with community and industry stakeholders, including the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, and I want to thank Laura Thomas and Joshua O’Neal from the San Francisco AIDS Foundation for their guidance. I also want to thank Blade Bannon, Race Bannon, and the many community members who have been advocating for these changes for their advocacy support and Tom Temprano in my office for his work.”

Published on February 27, 2020

Recent Comments