By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

Across his long and influential career, Ted Shawn (1891–1972) made many remarkable contributions to American dance, but his lifelong mission remained always to show that dancing was “a respectable profession for men” and “a legitimate medium for the creative male artist.” When he began his professional career in 1912, in the North Atlantic community of nations, the art had the reputation of being an especially feminine field, but Shawn was convinced he could change that.

In those far away times, America’s parents simply did not encourage their sons to consider a career in dance. Women who danced were lauded and adored, but the public saw male dancers as not only being light on their feet, but “light in the loafers.” Shawn himself originally planned to enter the ministry, until an illness he suffered when he was 19 caused him to become temporarily paralyzed from the waist down. Dancing became part of his physical therapy program.

After making a full recovery from his illness, Shawn became a professional dancer. In 1914 he met Ruth St. Denis, one of the pioneers of American dance performance. The next year, now married, they founded Denishawn, soon known as the “cradle of American modern dance,” and created a company, the Denishawn Dancers, to bring their work to the public. Their professional relationship ended in 1931, although they never divorced and remained close until St. Denis died in 1968.

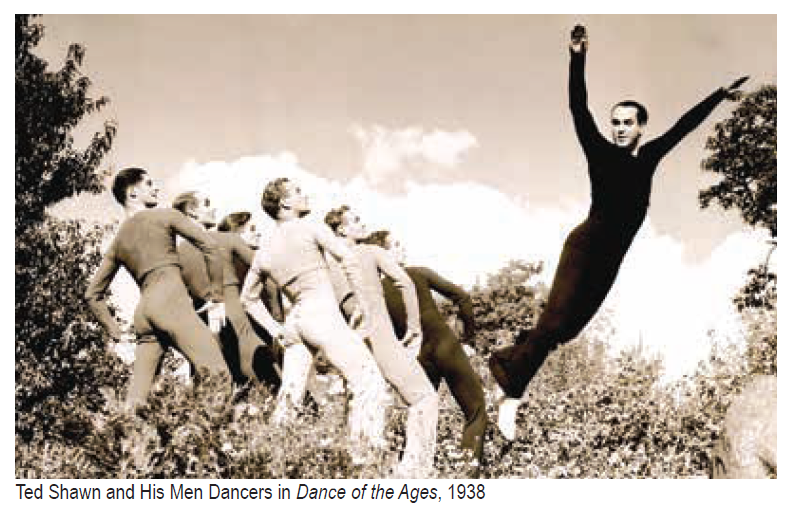

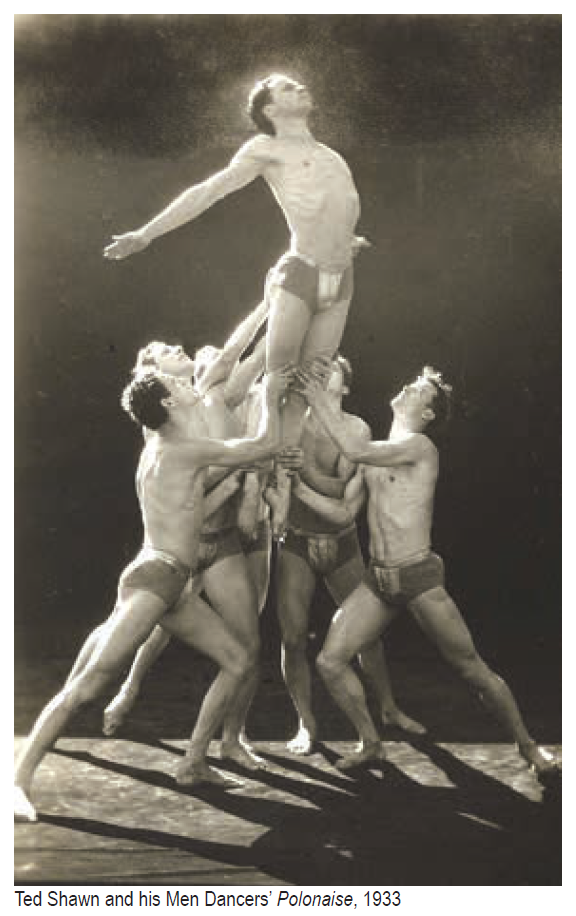

Shawn became determined to challenge what he described as the “false idea … that dancing is an effeminate expression for men.” Not only was it a respectable career, he argued, but an art that could be enjoyed for its own sake. Creating“the first company in modern times composed entirely of men dancers,” he presented “a program of dances essentially masculine in principle and performance” to “glorify men as men in all their physical beauty and graceful movement.”

Shawn chose the men for his first dance troupe more for their masculinity, athletic ability, and stamina than for their experience as performers, which was nil for most of them. One had lettered in football, baseball, basketball, and track during high school only a few years earlier. Another was a record-setting pole vaulter. A third was a champion swimmer. Some had taken dance classes, but only Barton Mumaw, who became his lover, had more than a minimum of dance training.

Ted Shawn and His Men Dancerspremiered its “great panoply of masculinity” in Boston on March 21, 1933, the first all-male dance concert in the United States. Critics were impressed. Lucien Price, editor of The Boston Globe and eventually a strong supporter of Shawn’s work, wrote, “The dancing of the young men was boldly original … . In your company for the first time, it seemed to me, I saw young Americans dancing as Americans and dancing in an art form.”

The program that first night included Cutting the Sugar Cane, which combined many of the elements Shawn stressed in his work: heroic themes, male bonding, athleticism, exotic settings, and minimal costumes. He had been inspired by the workers he saw on a visit to Cuba, where they “cut the tall stalks with gleaming machetes, moving with a design and rhythm accompanied by chants or shouts that together created a natural dance design.” The dancers wore “only of red neckerchiefs and full, white cotton Cuban work pants tied with a red belt.”

As Mumaw described the production, “Four workers are portrayed under the unrelenting heat of an equatorial sun while they slash, carry, and stack the sugar cane. When the overseer’s back is turned, they interrupt this work … to compete in executing different patterns of village dance steps. Then the overseer bursts upon this moment of levity to whip the men back to work … . But the leader exits with a final, cavorting leap of defiance that seems to cry, ‘Curses to you! Our spirits are high!'”

Although stereotypes and cultural appropriations abound that are no longer acceptable, Shaw believed he was sharing a masculine work of social consciousness. At the time, his presentation, Mumaw later wrote, “was considered by American audiences and press alike as authentic and erotic.” Other groups, including the Hampton Institute Creative Dance Group, founded in 1934 by Charles Williams and one of the first African American touring companies in America to perform in New York, also presented it, with Shaw’s support.

Seven years after its first public concert in Boston, the company appeared there for the last time on May 7, 1940, having appeared before more than a million people in 750 cities in North America and Europe. By then, Shawn had established Jacob’s Pillow in Becket, Massachusetts, as a center for teaching and presenting dance. It struggled at first, but endured. In 2003, the federal government declared it a National Historic Landmark District, “an exceptional cultural venue that holds value for all Americans.”

Shawn continued to be a role model and spokesman for the masculinity of dancers, but he was never able to reveal one important truth about himself: that he was in all ways a lover of men. During an era when homosexuality was illegal in every American state and territory, he knew very well that public knowledge of his sexuality would not only end his career, but also his crusade “to restore dancing for men to its rightful standing.”

Across his 50 years as a dancer and choreographer, Shaw brought almost every archetype—some would say stereotype—of maleness before the public. Was he successful in reshaping American views toward male dancers? Mumaw thought so, writing that Shawn “was able to change the attitude of an entire country toward men in dance.” Whether he did or not, Shawn made an enduring contribution to modern culture through his belief in “the art of dance” and its power “to lead humanity into continually higher and greater dimensions of existence.”Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on March 23, 2023

Recent Comments