By Jim Maloney–

It was a Monday afternoon in February of 2016, and I met up with the other volunteer running coaches of the 1000 Mile Club outside the East Gate of San Quentin State Prison in Marin County. This was my first day and I was nervous as I had never been inside a prison before. The coaches reassured me and put me at ease. We signed in, showed our ID, then made our way through the gate and past the prison administrative buildings to the highly-secured main entryway. We signed in again, had our ID’s run through the prison database to ensure we were cleared to go in, had our belongings checked, then proceeded through two heavy iron gates that each clanged shut behind us.

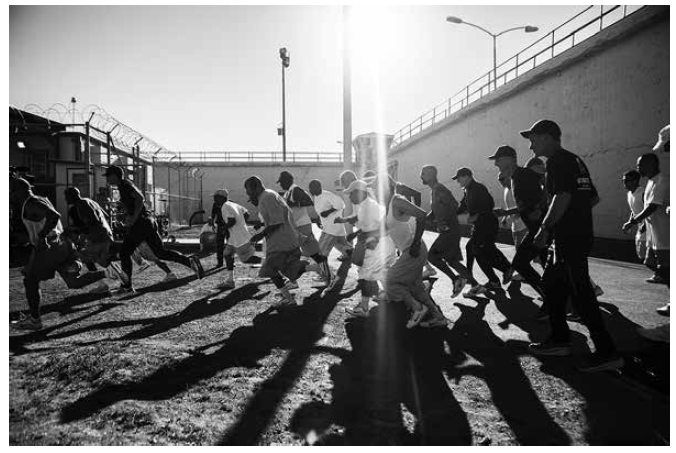

We were now inside the prison. We made our way past a beautifully manicured garden, turned right at the medical building, then left down the asphalt roadway and into the prison yard. It was a chilly evening and the wind swept in from the Bay. Hundreds of incarcerated men were milling about and involved in all sorts of activities, including running along the white-lined track that navigates the perimeter of the yard.

The men in the club were gathered at the far end of the prison yard next to the baseball field. I found them to be open and welcoming, and I proceeded to shake hands and introduce myself to them one by one, which worked to put me at ease. I was frankly surprised by how cordial and kind they were to me.

San Quentin State Prison is the oldest prison in California. It was built in 1854 by convicts from San Francisco and has been in continuous operation since. The prison has a storied and notorious past and houses all the incarcerated men of California’s Death Row. Today the prison is considered a model of innovative rehabilitative programming. The 1000 Mile Running Club is an example of one of those innovative programs.

The Club was inspired by former incarcerated runner, Ronnie Goodman, who grew up in (and was later paroled to) San Francisco. Ronnie was an avid runner and wanted to receive proper coaching, and approached prison programs director Laura Bowman for support. Bowman contacted Frank Ruona, then-president of the Tamalpa Runners Club in Marin County, asking if they would send in volunteers to coach the inmates. Ruona sent an email to the membership soliciting volunteers, got zero responses, then told Bowman: “Ok, I’ll do it myself.” Ruona, a veteran marathoner, ultra-runner, and running coach, proceeded to create the 1000 Mile Club with Goodman as its first, and sole, runner in 2003.

The name “1000 Mile Club” was inspired by the Lao Tzu quote: “A journey of 1000 miles starts with the first step.” The Club inspired others to take that first step into believing that running could be one pathway toward wellbeing, rehabilitation and personal transformation, and soon many others joined. A goal of members is to complete 1000 miles of running while incarcerated, and the men dutifully log their miles to document their progress.

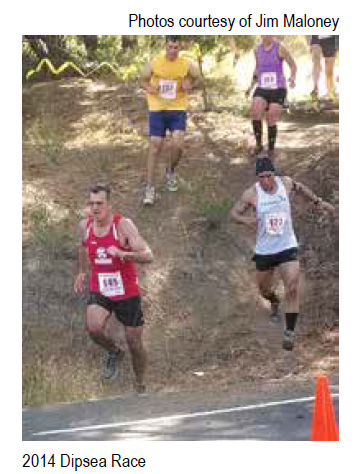

I learned about the 1000 Mile Club by chance through a friend who is a long-distance trail runner and volunteer coach for the club. I was touched by his sharing of how much he enjoyed the coaching, to the point he felt he got as much or more out of it than the incarcerated men did. I would come to understand what he meant. Inspired to learn more, I researched the club’s website where I discovered a photograph of Goodman, then paroled, running alongside me during a Dipsea Race in Marin in 2013. Wow, I thought this photograph was perhaps another sign that I should go for it. Though I had no idea what I was getting myself into, I was motivated to check it out and I was soon going into the prison to help coach.

Club activities consist of Monday evening training workouts and monthly Friday morning races of ever-increasing distances. Race season begins with a mile run in February and concludes in November with the annual San Quentin Prison Marathon—105 laps around the prison yard. A documentary of the marathon by filmmaker Christine Yoo, 26.2 to Life, premiered November 11 at the NYC DOC film festival to critical acclaim and features the stories of several of the runners.

To win release from prison, the incarcerated men have to demonstrate personal transformation. The running club and the marathon training offer a vehicle for self-improvement, a chance to be defined by more than their crime, and build and experience community. Many of our members join the club simply to get in shape and shed a few pounds, and then surprise themselves by going on to run a marathon—a feat that less than 1% of the population, incarcerated or free, ever accomplishes.

Of the 45 members of the club who have left prison, none have reoffended. The general reoffend rate in California prisons is roughly 65%. While there are many reasons for that perfect record, including their participation in a wealth of other programs at the prison, I believe the running club is a powerful force in helping the men challenge their beliefs about themselves and to set healthy goals and achieve things they never thought they were capable of. That belief in themselves and a reckoning that they are more than their crime offer a path toward personal healing and redemption.

The coaching experience has been deeply satisfying for me. I feel I’m contributing something special to these guys and they are incredibly appreciative of us being there. I do understand they committed serious crimes, and they were convicted and are now serving time for what they did. I don’t feel a need to revisit that. I focus on the fact that most of them will eventually get out of prison and how running can play an important role in their rehabilitation process.

Inspired by the work with the running club, I’ve since become a facilitator of a restorative justice-based men’s healing and rehabilitation program at the prison called Victim-Offender Education Group run by Insight Prison Project. I truly do get as much out of these programs as the men do.

Jim Maloney is a long-time member of the LGBTQ running clubs San Francisco Frontrunners and San Francisco Track & Field Club. He competes regularly in the Gay Games and in track and distance races in the Bay Area. He lives in San Francisco with his husband Andrew Nance.

Out of Left Field

Published on December 1, 2022

Recent Comments