By Gary M. Kramer—

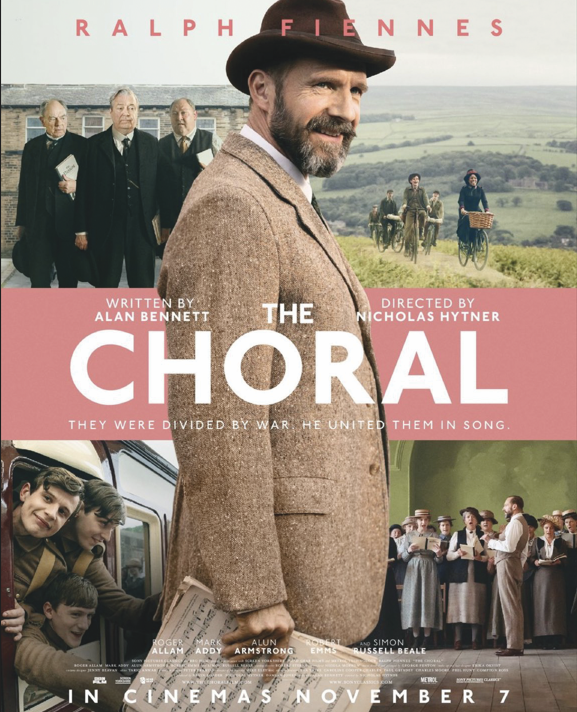

The Choral, directed by out gay filmmaker Nicholas Hytner and written by the out gay Alan Bennett, is a genteel period drama about making rousing music, but, alas, it rouses little more than a yawn.

In 1916 Ramden, Yorkshire, Alderman Duxbury (Roger Allam), the local mill owner, is planning to stage a performance of St. Matthew Passion. He hopes to entice the few men left in the town to sing as they need male voices. After the auditions, however, Duxbury’s chorus master enlists—the war is on, after all—and he must find a replacement. He reluctantly agrees to bring in Dr. Guthrie (Ralph Fiennes), but Guthrie is a bit of an outcast; not only did he spend years in—gasp!—Germany, but he is “not a family man.” (That is code for gay; the film does not speak about “the love that dare not speak its name.”)

A subplot involves Guthrie regularly checking on his German “friend” (code for lover) who enlisted in the war. Their relationship is discretely implied, as is the sexuality of Guthrie’s current pianist, Robert Horner (Robert Emms), who tells Guthrie that he would like to be his “friend,” but Guthrie denies him. (Perhaps because homosexuality was illegal at the time, but the film never mentions that either.) Robert instead becomes a conscientious objector when he gets called up to war. During his interview with the board, he is asked questions about sports and if he is a vegetarian, as if to queer bait him. Robert sticks to the courage of his convictions, acknowledging that it will result in punishment.

The Choral downplays the homosexuality and focuses on the relationships of the straight (and horny) young men in the chorus. Lofty (Olvier Briscombe) wants to lose his virginity before he goes off to war. His friend Ellis (Taylor Uttley) has eyes for Bella (Emily Fairn) whose boyfriend, Clyde (Jacob Dudman), is missing at war. Meanwhile, Mitch (Shaun Thomas) is attracted to Mary (Amara Okereke), a religious Salvation Army volunteer. An amusing scene has Mary’s mother (Cecilia Noble) addressing Mitch in a way that is contrary to what he expects from this formidable woman.

Hytner hits all the expected notes as this polished film unfolds, but the tone, which is meant to be reflective about war, comes off almost too restrained even for the British. The most dramatic moment has Guthrie deciding not to conduct St. Matthew Passion, but instead he selects The Dream of Gerontius

by Edward Elgar (out actor Simon Russell Beale, who has only one scene, but it’s marvelous). In tailoring Elgar’s oratorio to the talent on hand, and given the fact that he has a trio and not an orchestra, Guthrie makes some liberal changes, including staging the production with costumes, more like an opera. Another revision involves recasting the older Duxbury with—spoiler alert—the much younger Clyde, who returns from the war, injured, but with a beautiful voice intact.

The decision to stage the performance to reflect wartime generates some emotion, but The Choral never gets too heightened. This is the film’s blessing and curse. Hytner thankfully resists creating big operatic

moments for minor ones that tug at the heartstrings.

“Art is insensitive,” says Guthrie, making the point to be bold and daring, but the film itself never takes much of a chance. When an f-bomb or two is dropped, it is positively shocking; and during a few scenes of a sexual nature—one where a man asks to be pleasured, or another involving a man stripping naked—one can almost hear the pearls being clutched. In contrast, episodes involving a female sex worker are positively benign.

The singing is as lovely as the handsome period costumes and sets. The cinematography by Mike Eley is so crisp that one might wonder if wartime Britain should look so gorgeous. And the staging of The Dream of Gerontius has some inspired moments; the music is glorious.

The performances are as competent as the filmmaking. Fiennes plays Guthrie as fussy—cue him shrewdly admonishing Duxbury for crooning not singing and the contraltos about “having something against a B flat.” But, despite a few angry outbursts, Fiennes mostly underplays his part. His Guthrie could be darker, more intense, and even wounded, but Fiennes leans into Guthrie’s superiority and stoicism (when it comes to his sexuality). He feels both miscast and wasted here.

Among the large supporting cast, Allam delivers a poignant turn as Duxbury, a man who comes to appreciate the choral and what it provides him and the other singers, and Dudman is featured well as Clyde struggles to life in England after his duty. His interactions with Bella or some young men who are soon heading off to war strike wistful tones and hint at how strong the film could be.

The Choral is mostly inoffensive. Little is made about Mary being Black, and none of the references to homosexuality are negative. The film is sure to please its target audience, the Masterpiece Theatre crowd, and there is nothing wrong with that. But, for a film where the characters are grappling with the pain of war, loss, and even their sexuality, it is remarkably bland.

© 2026 Gary M. Kramer

Gary M. Kramer is the author of “Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews,” and the co-editor of “Directory of World Cinema: Argentina.” He teaches Short Attention Span Cinema at the Bryn Mawr Film Institute and is the moderator for Cinema Salon, a weekly film discussion group. Follow him on IG @garyemkramer

Film

Published on January 15, 2025

Recent Comments