Michele Karlsberg: How does the intersection of teaching and writing affect you?

Michele Karlsberg: How does the intersection of teaching and writing affect you?

Leslea Newman: According to George Bernard Shaw, “Those who can, do; those who can’t teach.” Hogwash! I propose a different adage: Those who can, teach; those who teach, change lives.

My mentor Allen Ginsberg changed my life by taking my work seriously. He studied every word, every comma, every line break of every poem I showed to him, as if my writing was important. Paying it forward, I extend the same courtesy to my students. The most important thing I can teach them is that their work matters. Which helps me remember that my work matters.

I can’t tell my students it’s important to write every day if I spend all my writing time posting on Facebook. I can’t tell my students how important it is to read serious works of literature if my literary diet consists solely of People magazine. I can’t tell my students to cut out all their clunky adverbs (“The crab meat filler of literature,” according to Stephen King) if my own writing is full of them.

I can’t tell my students it’s important to write every day if I spend all my writing time posting on Facebook. I can’t tell my students how important it is to read serious works of literature if my literary diet consists solely of People magazine. I can’t tell my students to cut out all their clunky adverbs (“The crab meat filler of literature,” according to Stephen King) if my own writing is full of them.

Teaching makes me a better writer because I have to listen to my own advice. And writing makes me a better teacher because the only way to learn how to write is to write, and what I learn practicing my craft is what I pass on to my students. And most importantly, paying it forward by helping emerging writers makes me a better person. Which makes me a better writer. Which makes me a better teacher. And round and round it goes.

Lesléa Newman is the author of 65 books for readers of all ages, including the children’s classic “Heather Has Two Mommies,” the novel-in-verse “October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard,” the short story collection “A Letter to Harvey Milk,” and the poetry collection “I Carry My Mother.”

Yarrott Benz: I’m unusual for a teaching writer because what I teach is in the visual arts, not in writing or literature. The subject I’ve taught the most often is architecture, and in that studio, spontaneous oral communication is key. During a critique, for example, whether it is the teacher or the student speaking, the skills of oral defense and criticism are essential. Often a class critique becomes a debate, and streamlining a thought to deliver it with an elegant, influential punch can mean a positive or negative verdict from the crowd.

Likewise, selling a design to a client is part of the process in architecture. Without the client you have no business. Clients often don’t know how to look at an abstract design, so walking them effectively through your ideas could not be more important. You have to describe the way it looks, yes, but you have to describe the way it works and the way it feels, too. The descriptions have to stimulate the imagination, but not overwhelm it. You work with the same economy of words as good copy writing for advertising.

Likewise, selling a design to a client is part of the process in architecture. Without the client you have no business. Clients often don’t know how to look at an abstract design, so walking them effectively through your ideas could not be more important. You have to describe the way it looks, yes, but you have to describe the way it works and the way it feels, too. The descriptions have to stimulate the imagination, but not overwhelm it. You work with the same economy of words as good copy writing for advertising.

I’ve taught architecture for twenty-three years. Encouraging students to speak about their work with power and simplicity has, no doubt, affected my own style of wordsmithing. At least, I hope it has. I hope I practice what I preach.

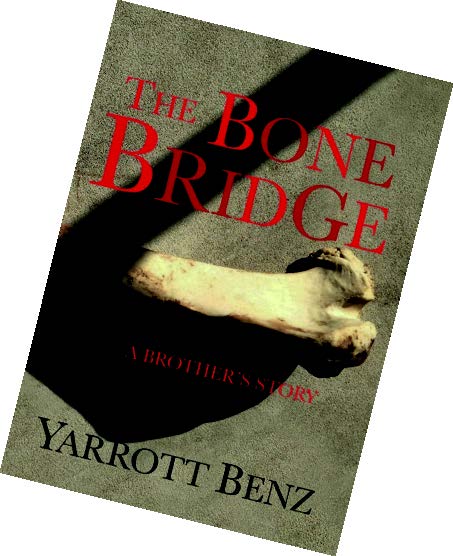

Artist, memoirist and essayist Yarrott Benz has written about architecture and the psychology of visual trends. Benz’s debut novel, “The Bone Bridge,” was published by Dagmar Miura in May of this year. Having taught for many years in New York City and Los Angeles, he now lives on a farm outside of Lexington, Kentucky.

Artist, memoirist and essayist Yarrott Benz has written about architecture and the psychology of visual trends. Benz’s debut novel, “The Bone Bridge,” was published by Dagmar Miura in May of this year. Having taught for many years in New York City and Los Angeles, he now lives on a farm outside of Lexington, Kentucky.

Michele Karlsberg Marketing and Management specializes in publicity for the LGBT community. This year, Karlsberg celebrates twenty-six years of successful book campaigns.

Recent Comments