By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

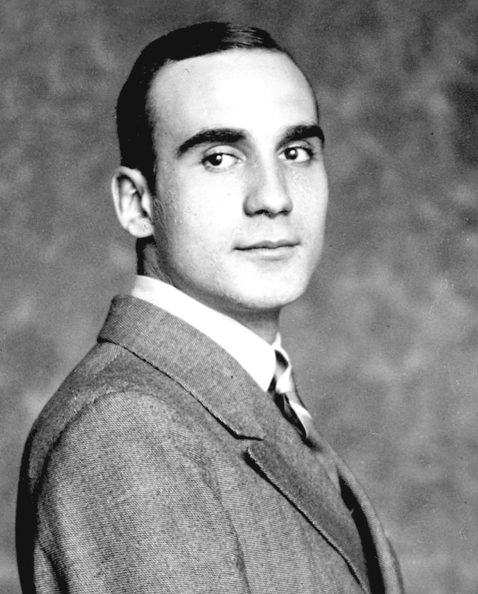

Many lovers of music consider Karol Szymanowski (1882–1937) to be Poland’s greatest composer since Frederick Chopin (1810–1849), with a body of work one critic described “as a dazzling personal synthesis of cultural references, crossing the boundaries of nation, race, and gender.” His peers agree. His “music is full of fascinating contradictions, vacillating between the archaic and modern, the religious and the hedonistic,” Polish pianist and composer Piotr Anderszewski (1969–) wrote. “He is like no other 20th-century composer.”

Szymanowski knew who he was at an early age, but it was a journey he made with writer and librettist Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz (1894–1980), his distant cousin and dear friend, to Italy, Sicily, and North Africa in 1914 that led him to embrace his true self in both his life and his art. Inspired by new ideas and old legends, he wrote Efebos, a long novel about Greek love, completed in 1918, and his enduring opera, Król Roger (King Roger), first performed in 1926 at the Grand Theatre, Warsaw.

The composer’s love of men was no secret. His colleague, pianist Arthur Rubinstein (1887–1982), knew immediately. “Karol had changed; I had already begun to be aware of [his homosexuality],” he wrote in My Many Years (1980), his autobiography, but “after his return, he raved about Sicily, especially Taormina. ‘There,’ he said, ‘I saw a few young men bathing who could be models for Antinous. I couldn’t take my eyes off them.’ … He told me all this with burning eyes.”

His novel was never published; the manuscript was turned to ash in 1939 when the Germans devastated Warsaw at the beginning of World War II. “In it I expressed much … on this matter,” he said later, “which is for me very important and very beautiful.” Only one section survives, which Szymanowski translated into Russian as a gift for Boris Kochno (1904–1990), then his lover, whom he met in Paris in 1919. Fortunately, the pleading homoerotic poems expressing his deep feelings for him, written in French, endure.

The two men were not together long. In 1921, Kochno had a brief affair with artist and set-designer Sergey Sudeikin (1882–1946), who introduced him to Sergei Diaghilev (1872–1929). The day after they met, the ballet impresario offered him employment as his secretary. Although their romance was not long lasting, either, Kochno continued to work with the maestro, writing the libretto for Stravinsky’s Mavra (1921), George Auric’s ‘s Les Fâcheux (1924), Henri Sauguet’s ‘s La Chatte (1927), and Sergei Prokofiev’s The Prodigal Son (1929).

Where did he find the time? While working with Diaghilev as his artistic advisor and principle collaborator, he had a “passionate affair” with American composer and songwriter Cole Porter (1891–1964), as well as Porter’s close friend, American diplomat Hermann Oelrichs, Jr. (1891–1948), whose mother and aunt built the famed Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. Eventually he met fashion illustrator and designer Christian Bérard (1902–1949), who was his life partner for 20 years. During the 1930s and 1940s, they were among the world’s most prominent same-sex couples.

Heartbroken that Kochno had left him for Diaghilev, Szymanowski was comforted by affairs with composer and music critic Zygmunt Mycielski (1907–1987), whom he met in 1926, musicologist Tadeusz Żakiej (1915–1994), and Witold Conti (1908–1944), a Polish film actor then at the beginning of his career; the romantic lead in nine features made between 1930 and 1937, his life as a matinee idol ended when the second World War began. He fled to France, where died in 1944 during the British bombardment of German military strongholds around Nice.

Szymanowski met Aleksander (Olek) Szymielewicz (1912–1944), his most enduring love, in 1931, just after his romance with Conti had ended. He was immediately enamored with his new friend, within a month writing, “To my dear, beloved Olek Szymielewicz, with the sincere wish that the rare gifts of internal and external charm and beauty which are his, may develop and strengthen, so that in the future he may become a ‘true’ and ‘profound’ man and not forget his friend, with whom life accidentally brought him together.”

No one doubted the composer’s deep feelings for Szymielewicz, who immediately brought him into his professional and personal circles. He engaged artist Maja Berezowska (1893–1978) to paint Olek’s portrait, which decorated his home in Zakopane near Poland’s border with Slovakia, now the Karol Szymanowski Museum. He also commissioned Benedykt Jerzy Dorys (1901–1990), famed fashion photographer and portraitist, who only rarely took such assignments, to create a series of nude art studies of Olek, probably the first in the history of Polish photography.

Not everyone was impressed by Olek. In her diary, Anna Iwaszkiewicz (1897–1979), who his openly bisexual cousin married in 1922, wrote, “Yes he is pretty, but stupid. What’s more, he looks as if he does not realize who Karol actually is and what an honor he is receiving (if his role can be honorable at all) that Karol has taken such care of him.” She was not alone. Referring to him as “the composer’s wife,” many friends and associates accused him of “excessive exploitation of Szymanowski’s innate kindness.”

The intimate relationship between Szymanowski and Olek may have ended as early as February 1932, but they never lost the great affection they shared. Writing to each other and visiting frequently, their friendship endured until the composer’s death in 1937. Under the maestro’s guidance, Olek found his way in life, graduating from medical school three years later. He became a true hero during the Warsaw Uprising, which began on August 1, 1944, giving care to wounded Polish soldiers and civilian patriots in an insurgent hospital.

Leonia Gradstein (1904–1984), once Szymanowski’s secretary and Olek’s landlady, but never an admirer, described his final days in her book Gorzka sława (Bitter Fame), written with Jerzy Waldorff, published in 1960. “When he was wounded, he refused to stop his work,” she wrote. Instead, he continued “treating those wounded even more severely than himself.” Under constant bombardment by the retreating German forces, the hospital building finally collapsed on August 26, 1944, killing over a thousand people, including Olek. His remains were never recovered.

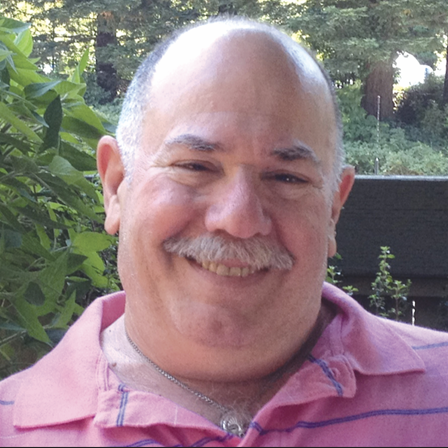

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on April 10, 2025

Recent Comments