By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney–

Two magnificent 103-year-old camphor trees stand together aside the majestic gate to the Meiji Shrine in the heart of Tokyo. A plaque underneath their broad and leafy branches proclaims that the trees “have grown under the protection of the deities to become huge and vivid and are considered to be sacred.”

The Meiji shrine is dedicated to the deified spirits of Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken. The Meiji period from 1868–1912 is of enormous importance to modern Japan. It marked the end of the Tokugawa period, famous for the rule of the shoguns and Japan’s isolation from most of the rest of the world. Faced with pressure from the United States and European countries, Japan during the Meiji period turned to the West. The country rapidly adopted many Western ideas, modernized, and grew to become a major world power.

Sadly one of the ideas Japan adopted from the West was homophobia. For centuries, Japan had been open to many forms of what today we might call queerness, perhaps most notably male homosexuality as part of samurai and Buddhist monastic culture. But during the Meiji period, Japan criminalized male same-sex sexual activity for the only time in its history—thankfully for only eight years. (Japan has never criminalized female homosexuality.) During the Meiji period, “there was a widespread belief that homosexuality was a perverted sexual desire which ought to be treated” as the Tokyo District Court explained very recently in its decision in the ongoing marriage equality litigation. Clearly, such ideas were linked to Japan’s embrace of the West.

Knowing this history, we felt a bit ill at ease visiting a shrine devoted to celebrating the Emperor Meiji. We were even more disturbed when we read the next bit of information on the plaque next to the camphor trees: the trees are renowned as the “husband and wife” trees. And these “coupled trees” are “a symbol of happy marriage and harmonious life within the family.”

Huh? These lovely trees are not simply trees for all to enjoy; they are married, heterosexual trees? If so, they clearly do not symbolize happy and harmonious married life for us or for other LGBTIQ couples in Japan who are denied the right to marry in Japan based on laws that grew out of Western influences cultivated during the Meiji period, the very era the shrine commemorates. The plaque further offers the wish to all visitors: “May happiness be brought to you through the divine power of these trees.” We knew that this blessing did not extend to us and other LGBTIQ people in Japan.

The shrine’s particular anthropomorphizing of the camphor trees became especially absurd to us after we did a bit of research regarding the biology of camphor trees. The University of Redlands website explains that the flowers of camphor trees are, in fact, “hermaphroditic, meaning that every flower contains a male and female part.” Thus, if one is going to anthropomorphize camphor trees, they are clearly not cisgendered and straight as the plaque proclaims, but instead intersexed and queer.

A few weeks ago, we had the opportunity to visit the ancient Miyajima Island shrine near Hiroshima, with its famous vermilion torii gate that appears to float on the water of the surrounding bay. Although a gate has existed on the spot for nearly 900 years, the current torii dates back to 1875. And it’s made of camphor wood because of wood’s strong resilience and its ability to resist decay from the salt water and other challenging elements of the environment in which it stands. Indeed, as we stopped to reflect, we realized that on the morning of August 6, 1945, these camphor trees that composed the torii not only stood witness to the mushroom cloud that rose in the sky just ten miles away in Hiroshima, but also withstood the radiation from the atomic blast.

Given all of this, we are tempted to lay claim to the camphor trees as a symbol of queerness and resilience in the face of adversity. But in the true spirit of the LGBTIQ movement, we prefer something else: let the camphor trees be themselves—strong and beautiful just as they are and always will be.

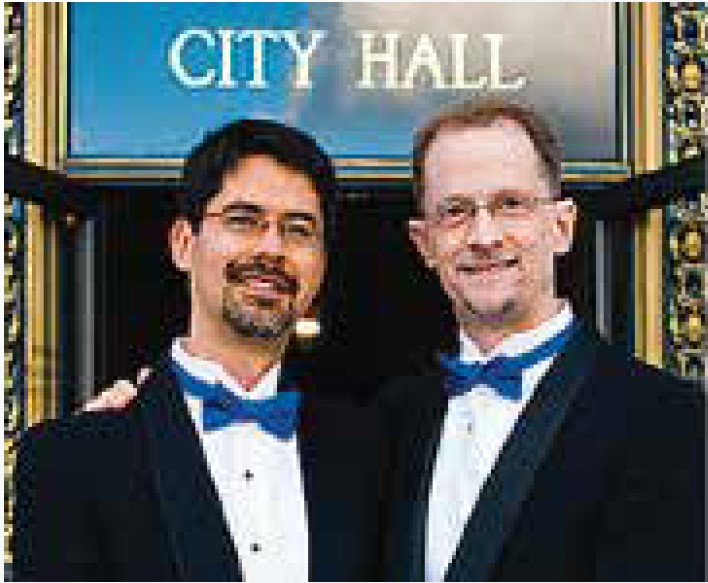

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

6/26 and Beyond

Published on March 23, 2023

Recent Comments