By Jewelle Gomez–

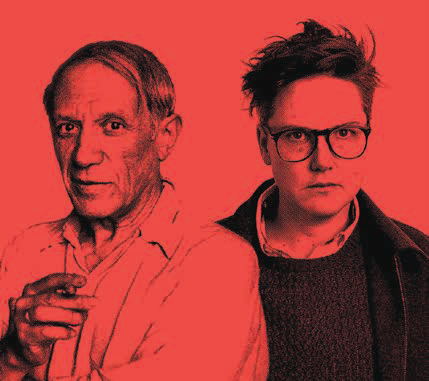

The New York Times’ scathing and somewhat puerile review (6.6.23) of humorist Hannah Gadsby’s feminist examination of the legend of Pablo Picasso at the Brooklyn Museum (which runs through September 24) lands far from the mark. It’s as if the reviewer dropped in from the 19th century and was startled that women did not like being objectified. He (who shall remain nameless here) feels so strongly about the play on words of the title of the exhibit, It’s Pablo-Matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby, that he claims to be unable to type the words, so he must cut and paste them. This is where the hyper-masculine sensibilities of the reviewer and his editor begin to give them away. Even art critic Robert Hughes referred to Picasso as “a walking scrotum,” according to Gadsby’s notes.

Stand-up performer Gadsby, a lesbian (they/them), has a degree in art history and curatorship, and uses a section from one of her monologues to examine some of Picasso’s work to tie his stated position that women are “goddesses or doormats” to his actual art. However, the reviewer essentially tries to dismiss the significance of Picasso’s restricted view of women in the service of maintaining his preeminent position in the pantheon of great artists. The reviewer’s assessment is a perfect example of the fragile male ego protecting his privates while he’s being shot in the head.

In the interest of full disclosure, Australian Gadsby and I share a literary agent. But it’s not that remote professional connection that inspires this column. (After all, there are only one thousand lesbians in the entire world, right?) But rather it is the insightful and inciting nature of Gadsby’s exploration of an artist deemed so popular that he’s considered unassailable. One of my favorite buttons in the 1970s was “Question Authority,” and I still believe that is where we must begin in order to reach full equality.

Many of the criticisms from the Times reviewer have nothing to do with what Gadsby is trying to accomplish. One complaint, for example, is that there’s no catalogue for the exhibit. What does that have to do with the installation as a whole? There are so many fully explanatory, cogent, historical notes—written and in audio recordings—which accompany each piece, such that viewers have an interactive experience all the way through.

Gadsby’s goal isn’t to fill the world with glossy, paper paeans to her own scholarship, but to give women and all people an experience that will engender the power to have a critical eye when looking at art depicting women. How many times do I have to view representations, either visual or literary, of “vagina dentata” before I call out that I’m being labeled an emasculator?

Another complaint from the reviewer is that “this new exhibition backs away from close looking for the affirmative comforts of social-justice-themed pop culture … .” Is that like being told to smile? It’s irrelevant to the exhibition’s goal. The reviewer also mistakenly indicates the exhibit, which rolls through several galleries, is too small. As we know, size is in the eye of the beholder.

As a monologuist, Gadsby knows how effective humor is in making a point. She wields this tool in many of her notes, which the reviewer dismisses as quips as if there is only one, classical way to comment on art. Based on the laughter and animated conversations around me in the galleries, Gadsby was totally on target.

After reading the Times review it might be determined that Picasso was so unassailable that Gadsby was spitting in the wind. The opposite is true. Gadsby isn’t the first, nor will they be the last, to reexamine the canon of the traditional art world to reposition our expectations and refocus our vision. The Guerilla Girls, cited extensively by Gadsby, raised feminist critique to an art form. This is one of the ways that the creation and appreciation of art in society evolves. And I don’t imagine the exorbitant price of a single Picasso canvas has suffered after his work is reexamined.

Gadsby also uses the work of more recent female artists like Louise Bourgeois, Mickalene Thomas, Dindga McCannon and Marilyn Minter to give context to the legacy of a dominant figure like Picasso. For inexplicable reasons, the reviewer believes they are being insulted by being included in this exhibit’s discussion.

When a lesbian opens people’s eyes, we are suspect and easily diminished. Remember the phrase meant to demean us and keep us in our place: “the lavender menace”? Let’s all order t-shirts!

Jewelle Gomez is a lesbian/feminist activist, novelist, poet, and playwright. She’s written for “The Advocate,” “Ms. Magazine,” “Black Scholar,” “The San Francisco Chronicle,” “The New York Times,” and “The Village Voice.” Follow her on Instagram and Twitter @VampyreVamp

Leave Signs

Published on July 13, 2023

Recent Comments