By Bill Lipsky–

The scandal began almost the moment the good doctor died on July 25, 1865, at his home in London. Although he had left specific orders to be buried immediately, in the garments he was wearing at the time of his passing and without an autopsy or any traditional preparations, a London housemaid, given the task of preparing the body for transportation, decided to replace his nightclothes with more suitable attire. Her revelation that James Barry’s remains were those of “a perfect female” caused a controversy that still endures.

His personal physician, Major D. R. McKinnon, who certified Barry as male on his death certificate, immediately denied the claim, but deepened the mystery. “It was none of my business whether Dr. Barry was a male or a female,” he wrote, although “I thought it as likely he might be neither, viz. an imperfectly developed man.” But “whether Barry was male, female, or hermaphrodite [intersex] I do not know, nor had I any purpose in making the discovery as I could positively swear to the identity of the body.”

The second child of Mary Anne and Jeremiah Bulkley, Barry was born in Cork, Ireland, in 1789, the year that George Washington became the first president of the United States. Identified as female, she was given the name Margaret Anne. Careers for women then were mostly limited to marriage (although she lacked the social standing to marry well), motherhood, midwifery, domestic service, and harlotry. With some education, she might become a teacher or a governess. None was to the future doctor’s liking.

When financial misfortune struck the family in 1804, Mrs. Bulkley left Ireland with daughter Margaret Anne to seek help from her brother James Barry, a celebrated artist and professor of painting at London’s Royal Academy; he died in 1806. Three years later, with the help of influential family friends, his niece, and adopting her uncle’s name, Barry was admitted as a man to the medical school of the University of Edinburgh, considered to be the most eminent in the English-speaking world. He was never again seen in public as a woman.

Barry began his studies as a “library and medical student,” eventually taking more courses than almost anyone else in his year. Although he was less than five feet tall, had “delicate features,” and spoke in a “high voice,” no one doubted his male gender, at least not openly. Some members of the University Senate tried to stop him from taking his final examinations, but only because they thought he was underage, not because they thought he was anyone other than who he said he was.

Barry graduated as a Medicinae Doctor in 1812 and was certified by the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1813. He accepted a commission as a Hospital Assistant in the British Army soon after. Two years later, he was made an Assistant Surgeon to the Forces and assigned to the garrison at Cape Town, South Africa. During his 12 years there, he not only established new standards of health care, but he also demanded all patients be treated equally, regardless of their race, social standing, or affliction.

At Cape Town, Barry became a dear personal friend of the colony’s governor, Charles, Lord Somerset, who appointed him Colonial Medical Inspector in 1822. Their closeness eventually led to rumors that they were intimate in all ways, when same-sex intimacy was illegal everywhere in the British Empire. An investigation, which cleared both men of any wrongdoing, could have been avoided had Somerset, who may or may not have known the doctor’s birth gender, simply stated publicly that Barry was female. He never did.

Barry was recognized for his achievements with praise and promotions. He was particularly proud that he “had the thanks of the Duke of Wellington” for his work on Malta during a cholera epidemic, where he was Principal Medical Officer from 1846–1851. His efforts during the Crimean War (1854–1856) earned him commendation from Edmund, Lord Lyons, then commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, for his “zeal and services” on board the HMS Modeste, a Royal Navy corvette, and for his “successful treatment of the sick and the purification of the ship.”

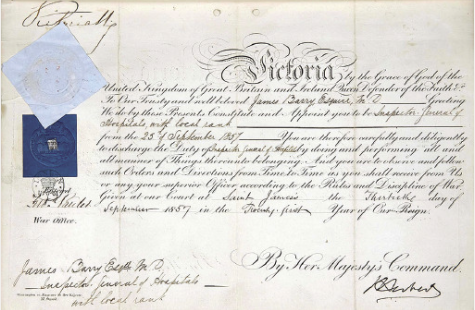

For all he accomplished during the Crimean War, Barry was promoted “By Her Majesty’s Command” to the position of Inspector General of Hospitals, his certificate of appointment signed by the queen herself. Then the second-highest medical office in the British Army and equivalent in rank to a brigadier general, Barry was appointed to oversee all military hospitals in Canada, his last assignment. He also received “a magnificent diamond ring from the Archduke Maximilian,” later proclaimed as Emperor of Mexico, “for services to one of His Imperial Highness’ crew.”

Not everyone was enamored with the good doctor and the way he practiced medicine. In an article published in All the Year Round, a British weekly literary magazine founded and owned by Charles Dickens, an anonymous observer wrote in 1867, “When first called in to a patient, ‘he would have the room cleared of everything previously prescribed … . ‘ If the patient recovered, Doctor James had all the merit; if death ensued, ‘Doctor James had unfortunately been summoned when the case was hopeless.’”

Barry also made powerful enemies because of his sometimes-caustic personality. Florence Nightingale, acknowledged as the founder of modern nursing, wrote of a confrontation they had during the Crimean War. “I never had such a blackguard rating in all my life—I who have had more than any woman.” The doctor “kept me standing in the midst of quite a crowd of soldiers…during the scolding I received, while [he] behaved like a brute… . [He] was the most hardened creature I ever met.”

Across his 50 years in the army, Barry had an influence on the development of modern military medicine that was significant. He reformed medical practice; introduced new surgical techniques (in 1826, he performed possibly the first successful caesarean section, saving both mother and child at a time when the procedure was invariably fatal for the mother); improved hygiene; and advocated for a healthier diet and better living conditions for soldiers, prisoners, and enslaved people wherever he was stationed, from South Africa to posts in the Mediterranean and the Caribbean. He saved thousands of lives.

Was Barry a woman posing as a man to have a career that society then denied to women? An individual born with the physical attributes of both sexes? A man whose gender was misidentified at birth? Surviving documents support all three possibilities, but none of that really matters. For his entire adult life, publicly, professionally and privately, Barry gave his word to one and all that he was a man. As the world’s leading expert about himself, let us take him at his word.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces From Our LGBTQ Past

Published on June 12, 2025

Recent Comments