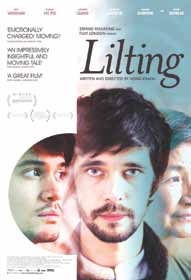

Lilting, written and directed by the openly gay Hong Khaou, is a subtle and moving chamber drama about the communication gap between Richard (Ben Whishaw) and Junn (Pei Pei Cheng). Both are mourning the loss of Kai (Andrew Leung), Junn’s son and—unbeknownst to his mother—Richard’s lover. But Richard doesn’t speak Mandarin, and Junn does not speak English, so Richard hires Vann (Naomi Christie) to help translate and bridge the gulf between them. Vann also assists Junn with communicating with a British man, Alan (Peter Bowles).

Lilting, written and directed by the openly gay Hong Khaou, is a subtle and moving chamber drama about the communication gap between Richard (Ben Whishaw) and Junn (Pei Pei Cheng). Both are mourning the loss of Kai (Andrew Leung), Junn’s son and—unbeknownst to his mother—Richard’s lover. But Richard doesn’t speak Mandarin, and Junn does not speak English, so Richard hires Vann (Naomi Christie) to help translate and bridge the gulf between them. Vann also assists Junn with communicating with a British man, Alan (Peter Bowles).

Khaou’s film deftly addresses the loss both mother and lover suffer as they grieve. The performances by Whishaw and Cheng, especially, are very affecting, and the film builds to an emotionally powerful climax. Via Skype from London, where he lives, the Chinese-Cambodian Khaou spoke with me for the San Francisco Bay Times about how he came to create his lovely film.

“When I wrote Lilting, it was a play about a daughter and her husband,” he explained. “There were no gay characters. It never got staged, but I felt something was missing. So when the opportunity arose to turn it into the film, I changed it to a son who could not be openly gay to his mother.” He continued, “That dynamic echoed onto the rest of the film and how communication and language is critical. My premise was that communication should bridge cultural differences and bring understanding. But it also has conflicts, like Junn’s relationship with Alan.”

“When I wrote Lilting, it was a play about a daughter and her husband,” he explained. “There were no gay characters. It never got staged, but I felt something was missing. So when the opportunity arose to turn it into the film, I changed it to a son who could not be openly gay to his mother.” He continued, “That dynamic echoed onto the rest of the film and how communication and language is critical. My premise was that communication should bridge cultural differences and bring understanding. But it also has conflicts, like Junn’s relationship with Alan.”

Lilting is not an autobiographical work, but it is a personal story. Khou’s father passed away when he was very young, and the idea of writing about grief involved the filmmaker revisiting those feelings. Like Junn in the film, Khaou’s mother experienced difficulty assimilating in the U.K., where Khaou and his family have lived for 30 years.

“She still doesn’t speak English,” the filmmaker said about his mother. “I took that as a premise, and I imagined how someone like that would cope if her lifeline to the outside world [her son] was taken away.”

While Lilting includes a subplot about Kai’s concerns about coming out to Junn, Khaou came out to his mother without incident. “She was absolutely fine,” he reported, and discussed the process of coming out that is exclusive to LGBT individuals. “There’s an age-old fear of disappointing our parents, and the shame that goes with it. The act of doing it—it sounds like we’ve done something devious, or deceitful. It’s harder in certain cultures, but I wouldn’t know if it’s become easier in Asian culture. I think coming out is hard in all cultures, even in the U.K., where men in their 50s are coming out, or America, where there is the ‘It Gets Better’ campaign.”

While the topic of sexual identity is part of Lilting, much of the film involves Richard using Vann to “talk” to Junn and help her adjust to life without Kai. The film is often talky, with characters translating dialogue back and forth within a single scene, but Khaou wanted to emphasize the time it took to exchange a thought and the frustration Richard and Junn both had trying to converse.

While the topic of sexual identity is part of Lilting, much of the film involves Richard using Vann to “talk” to Junn and help her adjust to life without Kai. The film is often talky, with characters translating dialogue back and forth within a single scene, but Khaou wanted to emphasize the time it took to exchange a thought and the frustration Richard and Junn both had trying to converse.

He acknowledged, “I think that was always a concern that we were repeating the info in having the translator there, but Vann is an interesting device. She can comment on miscommunication, and the awkwardness of communicating, and how things are lost in translation. There was a concern she might slow the momentum down, but if the scene is engaging, and has strong drama, it works.”

Lilting includes what Khaou calls, “silent spaces” between the conversations to balance out the drama, and give audiences a time to absorb all of the exchanges. Given this approach to the story, the filmmaker needed to hire actors who could embody the complex, interior emotions of the characters. Khaou specifically wanted Ben Whishaw for Richard, because he felt the out actor “carries a sense of truth” in him.

He observed, “I needed an actor with vulnerability and strength. He carries so much pain. Without Ben, all of the nuance could get lost, and the dialogue could feel very theatrical. He makes you hang on every word.”

Khaou had similar praise for Pei Pei Cheng. “She doesn’t have a lot of dialogue, so she needed to be very expressive. Pei Pei has been incredibly expressive even in the kung fu movies she’s been in.”

It was also important for Khaou to have the two characters expressing grief in different ways. He deliberately eschewed following a conventional narrative formula and insisted on flashing back and forth in time to tell the story.

“The narrative structure came through naturally,” the director remarked. “The repetition of the opening scene was to underscore not just the idea of memory, but also memory dealing with grief. It’s odd the way one grieves. You get stuck on a memory and you keep returning to that memory. You know it’s unhealthy, but you keep clinging on to it. I wanted to convey the idea of grief permeating, and the present and past existing on a continuous timeline.”

Lilting envelops viewers in Junn and Richard’s grief, but this thoughtful, gentle film is never depressing. In fact, it’s rather life affirming because of Khaou’s attention to detail.

© 2014 Gary M. Kramer

Gary M. Kramer is the author of “Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews,” and the co-editor of “Directory of World Cinema: Argentina.” Follow him on Twitter @garymkramer

Recent Comments