The passing years have preserved the privacy and buried the secrets that the women and men of earlier generations needed to keep in life, but in other ways have been unkind to them. They now seem frozen in time, looking stiff and remote, before the camera could capture color, spontaneity, and unaffected ease. As Jean Cocteau said in a different context, “A plaster cast is exactly like the original except in everything.” So too do early photographs show everything about their subjects, except who they were.

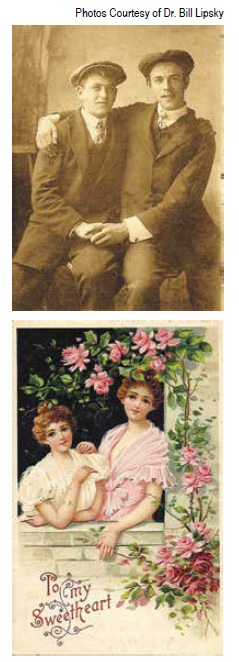

Here are two friends, gazing at us from a daguerreotype created more than 150 years, almost certainly born before San Francisco itself came into existence, sitting next to each other, arm in arm. We do not know their names or occupations, although their clothes indicate that probably they were laborers or artisans. They appear to be in their middle 20s, so we can only be sure that they valued each other enough to spend the time—and the money—to have their picture taken, possibly for the only time in their lives.

Here are two friends, gazing at us from a daguerreotype created more than 150 years, almost certainly born before San Francisco itself came into existence, sitting next to each other, arm in arm. We do not know their names or occupations, although their clothes indicate that probably they were laborers or artisans. They appear to be in their middle 20s, so we can only be sure that they valued each other enough to spend the time—and the money—to have their picture taken, possibly for the only time in their lives.

Does the affection they show for each other by their pose, one locking the other close to him, indicate a more intimate relationship? They lived and loved in a world very different from ours, with different understandings of themselves and each other, and what we see in their photograph might not be what they saw in it. Still, images of closeness and affection like theirs are much rarer than those showing friends sitting stiffly together, whatever their feelings toward each other might have been.

We have similar photographs from the same period of women, just as anonymous, posed equally closely together, looking equally affectionate. What were they to each other? More questions surround the photographs of them wearing men’s clothes. Some clearly show friends dressed for a class play or a fancy dress, but many seem entirely serious. Possibly they were expressing something personal about themselves. Possibly not. We have much still to learn about our predecessors.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Americans not only accepted, but also believed in intense, affectionate bonds between two men or two women, as long as they remained platonic, of course. Called “romantic friendships,” “smashes,” “crushes,” and “spoons,” they not only were quite common, but also society accepted and even encouraged them among the younger generation because many saw them as good preparation for marriage, when one person had to be devoted to another.

Couples held hands, walked arm in arm, hugged, and kissed in public without a single raised eyebrow among the guardians of other people’s morality. They showered each other with gifts, sometimes even locks of hair, and jealousy could become a problem. Sexual familiarity, of course, was forbidden, but people then believed there could be intimacy without orgasm. They openly displayed affection in ways that we now do not, given the last hundred years of psychiatry’s theories of sexuality, family fears, and social, religious, and legal constraints.

Two people enjoying a romantic friendship often took their photograph together. This may explain a studio portrait, from later in the 19th century, showing a pair of young men sharing a chair, arms around each other, gazing lovingly into each other’s eyes. We know they are not brothers—brothers never looked at each other so longingly—but little else. Possibly they were taking advantage of the innocence of being “smashed” on each other to conceal a fully intimate relationship. Everything about them remains a mystery.

Even when we have some information, the mystery remains. Posing for a photographer in their dapper Sunday suits and jaunty newsboy caps, two other men also sit closely together, arms around each other, holding hands. One has given himself a carefree smile, but his friend’s expression is wistful, his eyes filled with sadness, which the comment on the back of the image may explain: “Jack left for war, August 5, 1914,” the day after Great Britain declared war on Germany.

We can guess which one of them was Jack, but who was his friend? Were they as close as the image suggests to modern eyes? Probably we will never know. We can only hope that Jack returned safely from the war and imagine that the two friends enjoyed a long and happy life together. The true nature of their relationship and their fates remain Gordian problems.

More information does not always help us. What is happening in the photograph of the Olympian Council, a literary and debating society at Gustavus Adolphus College, its membership then limited to 20 male students? In 1907 they and their guests posed for a typical group portrait at their second banquet. Yet in the center of image two young men are locked in a passionate embrace, kissing each other on the lips. To us, this seems a scandalous public display of affection for the times.

Were they being serious? Were they clowning for the camera? Was everyone in on the prank, if it was a prank? No one seems the least bit concerned. Luther Falk, a member of the organization, sent the photograph to Miss Christina Peterson, writing on the back, “I am well and hope these lines will bring some joy.” He never referred to any untoward behavior or liberties his fellows were taking with each other. We have much more to learn about our predecessors.

Mysteries aside, when we allow ourselves to be drawn toward the subjects in these images, we find that the camera actually has captured more than the light reflected from their faces a hundred or more years ago. Taking in the details of their world, we begin to see that something else about them also has endured: the great fondness and affection they felt for each other; however, they expressed the endearment between them privately. Such is the power of old photographs and the endurance of human love and devotion.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on March 12, 2020

Recent Comments