By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

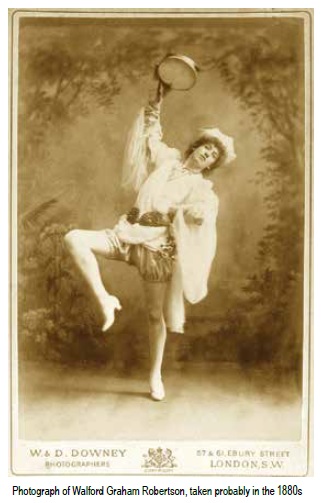

W. (for Walford) Graham Robertson, painter, playwright, and set designer, knew simply everybody. Among the elegant and fashionable of London and Paris, he was dear friends with each and all from Sarah Bernhardt to Henry James to James McNeill Whistler. Extremely attractive, according to contemporaries, “a gentleman from sole to crown, clean favored, and imperially slim,” he was one of those pale “fin de siècle” aesthetes whom Oscar Wilde called ”exquisite Aeolian harps that play in the breeze of my matchless talk.” He was his generation’s ultimate twink.

At least Wilde thought so. The two men met in 1887. Their love affair did not last long, but they remained devoted companions. When Wilde came to write The Picture of Dorian Gray three years later, his description of the title character seemed based upon Robertson’s appearance and appeal: “Yes, he was certainly wonderfully handsome, with his finely curved scarlet lips, his frank blue eyes, his crisp gold hair … . All the candor of youth was there, as well as all youth’s passionate purity.”

Wilde included Robertson in the circle of kindred spirits he asked to wear a green carnation to the opening night of Lady Windermere’s Fan on February 20, 1892. “I want a good many men to wear them,” he said. When Robertson asked him, “What does it mean?” he replied, “Nothing whatever, but that is just what nobody will guess.” Of course, Oscar, with his classical education, knew better. Carnations were a traditional symbol of the anus and green had been associated with homosexuality for centuries.

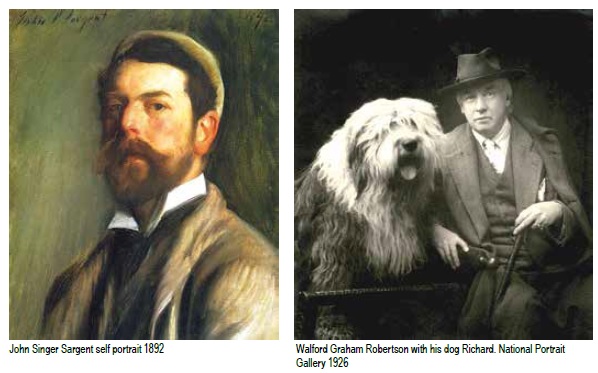

John Singer Sargent apparently thought Robertson was aesthetic youth personified, too. In 1894, when all of society wanted to schedule a sitting, the painter invited Robertson specifically to pose for him. “Why a very thin boy in a very tight coat should have struck him as a subject worthy of treatment I never discovered,” he reminisced later,” but he “evidently had the finished picture in his mind from the first.” Once, Sargent asked Robertson why he had never done a self-portrait. ”Because,” he replied, ”I am not my style.”

Their sessions took place during the summer and Robertson “feebly rebelled” against wearing the thick overcoat the artist had him pose in. “But the coat is the picture,” Sargent insisted. “You must wear it.” After Robertson told him, “Then I can’t wear anything else,” he began to “sacrifice most of my wardrobe.” Robertson became “thinner and thinner, much to the satisfaction of the artist, who used to pull and drag the unfortunate coat more and more closely round me until it might have been draping a lamp-post.”

Neither man shared whether Sargent was annoyed or enjoyed the slow strip tease. In addition to the coat, however, the artist also requested that Robertson bring Mouton, his French poodle, to be included in the portrait. Mouton “claimed rather unusual privileges and was always allowed one bite by Sargent,” not the usual artist-model relationship. “’He has bitten me now,’ Sargent would remark mildly, ‘so we can go ahead.'” The painting, famous even before it was finished, easily could have been done to illustrate Dorian Gray.

Both Robertson and Sargent attended the first performance of Guy Domville, the only play Henry James ever wrote, on January 5, 1895. During his curtain call the author was driven off the stage. “I have never heard any sound more devastating than the crescendo of booing that ensued,” Robertson remembered. Eventually he and James drifted apart, but James and Sargent, two lifelong bachelors, remained “real friends” whose “points of view were in many ways identical.” Robertson did not elaborate about what and how they saw eye to eye.

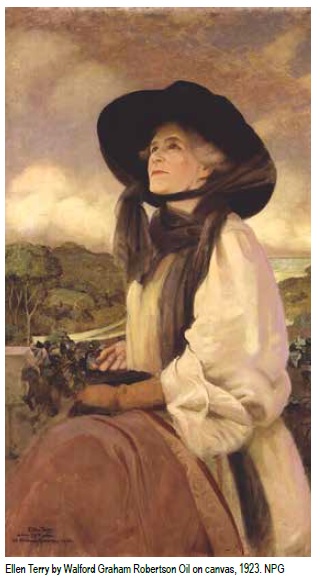

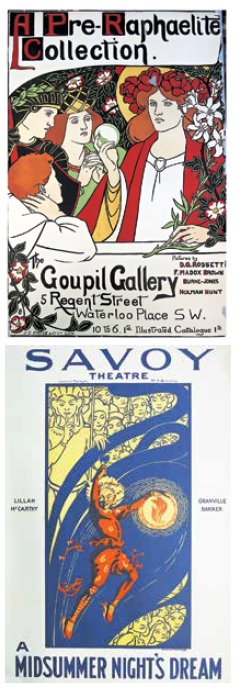

Robertson was born to wealth on July 8, 1866. Although he claimed his family’s London home was “pictureless, save for the inevitable Landseer engravings, without the aid of which a respectable Bayswater family could hardly have been expected to eat its dinner,” he decided at an early age on a career as a gentleman artist. He painted portraits of noted individuals, wrote and illustrated children’s books, designed sets for Ellen Terry and a golden robe for Bernhardt’s starring role in Wilde’s drama Salome.

He also became an art collector. When he was 16 or 17 years old—he himself could not remember—he became fascinated by the work of William Blake, the artist then out of fashion and little appreciated. “Despite severe qualms of conscience at the vast outlay,” he bought a Blake oil painting, The Ghost of a Flea, for £12, about $1600 today, a great bargain in any age. Eventually he had a substantial collection of Blake’s monoprints, large color prints, drawings, and paintings.

Robertson never married. He lived with his mother at their elegant townhouse at 23 Rutland Gate S.W., Knightsbridge, until her death in 1907. The era of elegant suppers, afternoon musicales, brittle conversation, gloves of grey suede, and walking sticks with jade handles was passing. With no desire to involve himself in ”an age to which I do not belong,” in 1914 he moved to a rural cottage in Surrey he had purchased in 1888. The house lacked electricity, central heating and hot water, but he never modernized it.

Claiming to be retired, he still “painted nearly every day” and kept up an enormous correspondence. His memoir, Time Was, appeared in 1931. Eight years later, at the beginning of World War II, he donated 21 Blakes to the Tate Gallery and also gave originals to the British Museum and other cultural institutions. Whatever his own successes, his gifts to the world of another man’s art may be his greatest and longest-lasting legacy. He died on September 4, 1948.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on July 16, 2020

Recent Comments