By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

Wakefield Poole created the modern gay adult film in 1971 when he was living in New York. Made on a budget of $4,000, Boys in the Sand was the first feature-length XXX motion picture ever produced with an all-male cast and the first to present interracial male-male intimacy. It was the first to include on-screen credits for its cast and crew, although many used noms de porn. It was the first to reviewed by Variety, the entertainment industry’s “journal of record,” and the first to gain mainstream credibility.

Variety announced the film’s popularity meant that “there are no more closets,”and Boys helped to bring about the era of “porno chic”: a brief period of open cultural acceptance of hardcore pornography. It also helped to change stereotypes of gay men by presenting its star, Casey Donovan (né Calvin Culver), as a clean-cut all American boy next door, although he certainly was less sexually reserved both on and off screen. Donovan became gay porn’s first celebrity superstar.

“I wanted [to make] a film that gay people could look at and say, ‘I don’t mind being gay—it’s beautiful to see those people do what they’re doing,'” Poole said some years later. Whatever their motivation, gays, straight couples, and women went to see the movie in record numbers; it made back its production cost in a single theater the day it opened. Unlike most gay adult films, which have a limited appeal of months or weeks, Boys is still in distribution after more than 50 years.

Poole directed two more adult films in New York before moving to San Francisco with his lover Peter Schneckenburger, who appeared in Boys in the Sand as Peter Fisk; a friend from New York, Harvey Milk, helped them find their first apartment. In 1975, they opened Hot Flash of America at 2351 Market Street as “a totally gay-owned enterprise.” Located half a block from 17th and Castro streets in what had been a hardware store, Poole “wanted to make sure it represented a truly complex view of the homosexual world.”

The view was indeed complex, although limited only to some in the LGBT community. Poole wrote in his autobiography that, on display and available for purchase, were “antique French marble candy counters beneath Lalique mirrors, next to San Francisco street lamps, beside a wicker chair, covered with Mao silk pillows, alongside a rubber chicken.” The inventory also included coffee mugs made to resemble a pair of cutoff Levi’s, erotic cloisonne jewelry, sterling silver joint holders, novelty items that cost a dollar, and original art costing thousands.

Living up to its motto—“Everything You Want But Nothing You Need!”—it was described by California Hotline as being “a super-creative store that is both an art gallery and a store with antiques and whatever—all distinctive.” The Advocate thought so, too. “A walk into Hot Flash can brighten even the bluest spirit,” it wrote. “They raise the concept of gift shops almost to an art form.”

All of this was a bit too much for the San Francisco Bay Guardian. Yes, Hot Flash was “easily the area’s arbiter, incontestably Castro Street’s pacesetter and benchmark, the apotheosis of what a gift shop can aspire to.” Ultimately, however, “Just like its mirrored bathroom, there’s too much paradox going on here.” Even “delineating what’s sold here is irrelevant because it changes constantly. This change is its real product … . This place has rhythm, the measure of now; its fingers firmly counting the pulse of the public’s pocket.”

Whether Hot Flash set trends or followed them, it became a very popular destination. The inventory changed every six weeks, then previewed with an invitation-only reception that included an exhibit of work by a local artist. It also had a hair salon in the rear of the store, so customers could get all prettified for their Saturday date in the back, then buy their beau a gift—anything from a

t-shirt to an original artwork—in the front, all in one stop.

The t-shirt, emboldened with a logo that was modeled after Arm & Hammer’s famous trademark, soon became an essential item in every Castro clone’s wardrobe, which also included tennis shoes or boots, snug 501s, a flannel shirt for cooler days, a polo shirt for dressier occasions, and a hooded jogging jacket (affectionately known as a “fag wrap”) or bomber jacket (green or black). Unfortunately, the clones bought more t-shirts than antiques, making it finally unprofitable. It closed in 1979.

Just behind Hot Flash, facing 17th Street, was the Beau Geste Cinema. It opened in May 1976 with a screening of This Is the Army starring Ronald Reagan, but its life as a revival house did not last long. By October it was showing gay adult films exclusively, the only XXX movie theater ever in the neighborhood. It became the East of Castro Club in 1979, its films now projected on the walls above the private booths on the first floor and the holed partitions in the balcony.

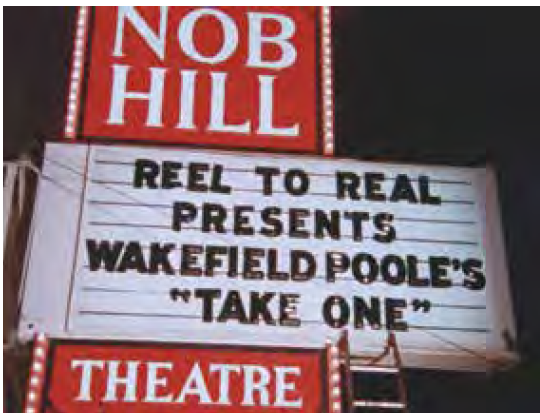

Clif Newman, who managed the new enterprise, also managed the Nob Hill Cinema, which previously had been a jazz club. He and Poole were good friends, so perhaps it was inevitable that the Nob Hill became the location for Take One, as well as its world premiere in 1977. Using documentary, performance art, and observational cinema techniques, Poole presented a series of interviews with gay San Franciscans, who discussed their lives and sexual fantasies before living them out in front of his camera.

Poole moved back to New York in 1980, where he had been a dancer and choreographer on Broadway and television before making Boys. He directed five more XXX features, then left the adult industry in 1985 to become a trained chef. After working as manager of food services for Calvin Klein Cosmetics in Manhattan from 1989 until 2003, he retired and moved to Florida, his childhood home. He died in 2021, exactly 50 years after his “little porno movie,” as he described it, began a revolution in gay adult film.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces From Our LGBT Past

Published on November 3, 2022

Recent Comments