By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

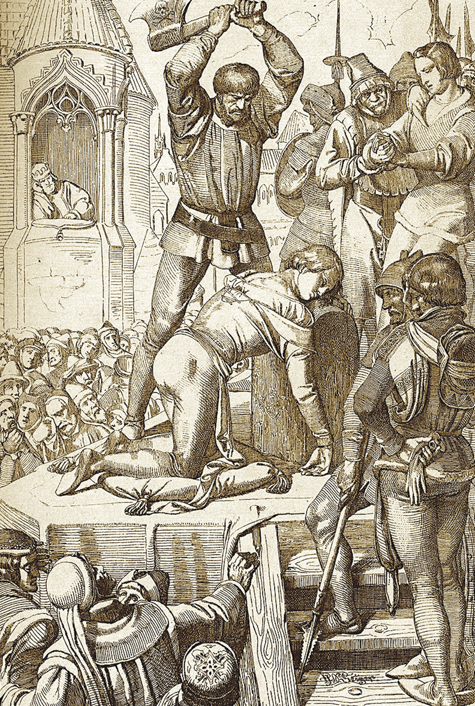

The multitude gathered early and eagerly to witness an event few could imagine they would ever see. Charles of Anjou (1226–1285), brother of Louis IX (1214–1270), King of France, had ordered the public execution of Conradin (1252–1268), Duke of Swabia and titular King of Jerusalem and Sicily, the last direct heir of the House of Hohenstaufen. With his beloved and constant companion, Frederick, Margrave of Baden (1249–1268), he was beheaded in the market square of Naples on October 29, 1268. He was 16 years old.

Such an event was virtually unprecedented. Rivals to a royal crown, captured in war, usually were imprisoned, not dispatched to eternity in public. However, Conradin and Frederick, who was 19 when he executed, had led a series of campaigns against Charles, the nominal ruler of Sicily for the previous two years, which almost succeeded in deposing him. Although Conradin had been excommunicated by the church and convicted of treason against the state, he became the hero, not the villain of his story.

His death created widespread outrage against the French in both Germany and Italy, where the young lord who was as “beautiful as Absalom, and spoke good Latin” remained “for centuries a figure of legend and romantic speculation.” According to the poet Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), as late as the 19th century “the Germans still held a grudge against the French for his execution.” By then, he and Frederick were not only figures of a lost cause, but also symbols of great nobility and “steadfast companionship.”

During the great age of Romanticism that captured the European and American imagination during Heine’s lifetime, Conradin and the deep affection he shared with Frederick inspired novels, dramas, poems, and artworks in Germany, France, England, and Italy. Among the earliest was “The Death of Conradin,” written by Felicia Hemans in 1824, who used the vivid imagery and lyrical style that the era so admired to describe both his singular nobility and the tragedy of human suffering in a world of natural beauty:

But thou, fair boy! the beautiful, the brave,

Thus passing from the dungeon to the

grave,

While all is yet around thee which can give

A charm to earth, and make it bless to live.

Charles Swain (1801–1874) made him the hero of his poem “Conradin,” published in 1833:

And yet, that youthful knight

Owns no dishonour’d like;

For, if the Victory crowned the right,

Young Conradin, ‘twere thine!

50 years later, William John Rous (1833–1914), who served as an officer of the 90th Regiment of Foot (Perthshire Volunteers) Light Infantry in the Crimean War, romanticized the great love between Conradin and Frederick across 56 pages of verse, especially when:

[Frederick] turns to clasp with longing

arms his friend,

And turning, sees the fatal blow descend,

Then presses with his lips the severed head,

Last greeting of the dying to the dead.

When C. R. Ashbee (1863–1942), a leader of the Arts and Crafts movement in England, published his long poem “Conradin” in 1908, which romanticized him into sentimentality, he dedicated it to his “patron and friend” Thomas Bradney Shaw-Hellier (1836–1910). A colonel in the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards and Director of the Royal Military School of Music, he retired to Taormina, Sicily, where, according to Ashbee, he surrounded himself with a bevy of Sicilian boy retainers … with large dreamy eyes.”

Were the two young nobles intimate in every way? In an age of chivalry and courtly love, men could express their deep affection for each other without anyone believing they had a sexual relation. When the medieval poet Marie de France (1160–1215) wrote of a king who embraced a beloved knight in “Lay of the WereWolf,” removing a curse upon him, and “kissed him fondly, above a hundred times,” she was not necessarily suggesting that there was anything more than “spiritual bonds” between them.

Others thought differently. Numerous chroniclers of the day wrote that many rulers enjoyed same-sex intimacy, including Kings Edward II, William Rufus, and Richard the Lion-Heart of England; Philip II of France; and others, including Robert, Duke of Normandy—and Conradin. Perhaps they were repeating claims made by their enemies, not their admirers, but European secular law mostly ignored homosexuality before the middle of the thirteenth century. Until then, sodomy cases were prosecuted in ecclesiastical courts, but rarely against the nobility.

The intense, loving relationship between Conradin and Frederick remained always central to the story. In his Impressions of Travel in Sicily (1842, Alexander Dumas (1802–1870) stated, “The two young men swore that nothing could separate them, not even death,” without explaining why. Edward Prime-Stevenson (1858–1942) was bolder. Writing about “the youthful and brave Conradin of Hohenstaufen and his beloved and not less gallant cousin, Frederick of Baden, the ‘blameless’ paragon of chivalry” in The Intersexes (1908), his pioneering history of “similisexualism,” he affirmed they “indubitably were homosexual.”

During the 20th century, more and more historians acknowledged the sexual nature of their relationship, which some did not think was admirable. Writing in 1930, Paul Wiegler (1878–1949) used coded language to disapprove, stating, “Young Conradin was a pale and fragile beauty,” a “delicate young German” who “quivered with the affection of a weakling for young Frederick of Baden, the son of Gertrude.” When he heard they had been sentenced to death, “Sobbing he embraced his friend, as a man a woman.”

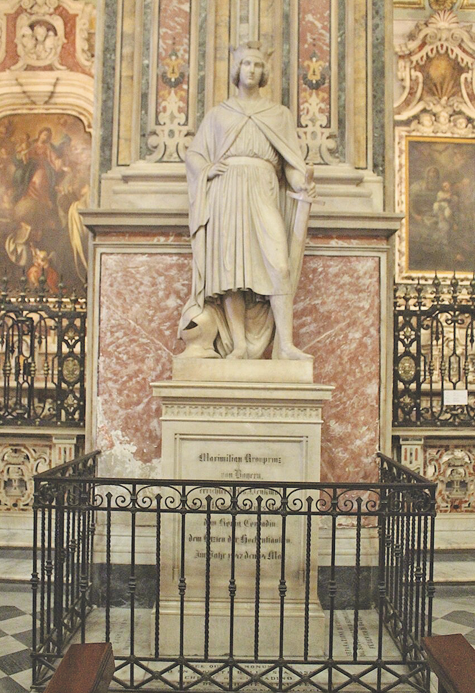

After their execution, “In a final act of intense disrespect, Charles ordered the corpses to be put away in the sea-sand, hard by the stony cemetery of the Jews.” Conrad’s mother, Elisabeth of Bavaria, later founded the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Naples, adjacent to the public square where they were put to death, for “the good of the souls of her young son and his companion, Frederick of Baden, as well as a resting place for their remains,” where they abide to this day.

Conradin built no castles or cathedrals. He founded no great cities, established no centers of learning, created no great libraries, commissioned no lasting works of art. Yet, we still care about him and his “great and good friend” Frederick, who perished together more than 750 years ago. We still celebrate them for sharing such deep love and devotion to each other that one willingly joined the other before their executioner. Their tomb is now a place of pilgrimage for loving gay couples from all over the world.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LBGTQ Past

Published on January 30, 2025

Recent Comments