By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

On the night of March 27, 1943, the Amsterdam Fire Department received a telephone call from the Gestapo. The Municipal Public Records Office was on fire. Led by someone wearing a police captain’s uniform, 15 men, an investigation showed later, had arrived at the building and asked the Nazi guards stationed there to open it for a special inspection. Once inside, they disabled the guards with drugs, then set the building on fire.

All 15 men were members of the Dutch Resistance. One was a historian by profession, one was an architect. Several were medical students. Others were civil servants or office clerks. None was a trained saboteur. They had no background in special operations or surgical strikes. What they brought to their task was their deep dedication, their opposition to tyranny, and their humanity.

Leading the group that night was Willem Arondeus (1894–1943), an openly gay Dutch artist and author, who fiercely resisted the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands from its earliest days. One of six children, he was 17 when he told his parents about his homosexuality. Although same-sex intimacy had been legal in the Netherlands since 1811, they were not pleased. He left home soon after, essentially ending all contact with his family.

He became a professional artist. Occasionally he won commissions for important works, including a mural for the Rotterdam town hall, but mostly he struggled for the next 20 years. His great joy of life, however, was Jan Tijssen, the son of a greengrocer. They met in 1933 in Apeldoorn, moved to Amsterdam, and lived openly together as a couple until the beginning of the war, when Arondeus sent him back to Apeldoorn for his safety.

During his time with Tijssen, Arondeus turned from art to literature. He published two novels; a biography of the Dutch Pre-Raphaelite painter Matthijs Maris, who fought to defend the radical Paris Commune in 1871; and a history, Figures and Problems of Monumental Painting in the Netherlands. By the time it appeared 1941, he was deeply involved with the Dutch resistance movement against the Nazis.

At first he produced and distributed several underground publications, urging all citizens to resist the fascist occupation of the Netherlands and calling for a mass movement to defy it. When he realized that appeals were not enough, he joined the sculptor Gerrit van der Veen to form the Raad van Verzet (Resistance Council), forging identity cards to protect Amsterdam’s Jewish community from deportation to concentration camps.

Arondeus and his colleagues soon discovered there was a serious problem with their forgeries: they could easily be proved false when compared to the information files in the Municipal Public Records Office. Finding more and more counterfeit documents, the Nazis were doing exactly that, making the bureau’s existence a serious obstacle to rescuing the persecuted. The solution: destroy the records in the building by blowing it up.

Their plan, as daring as it was dangerous, was only partially successful. Although they badly damaged the building, it was not completely destroyed. The group managed to destroy 800,000 identity cards; thousands more, smoke damaged and water damaged, now were mostly unreadable. They also upended filing cabinets and scattered contents, making surviving documents unusable for weeks. Unfortunately, they had not incinerated the entire archive of some 5,000,000 records.

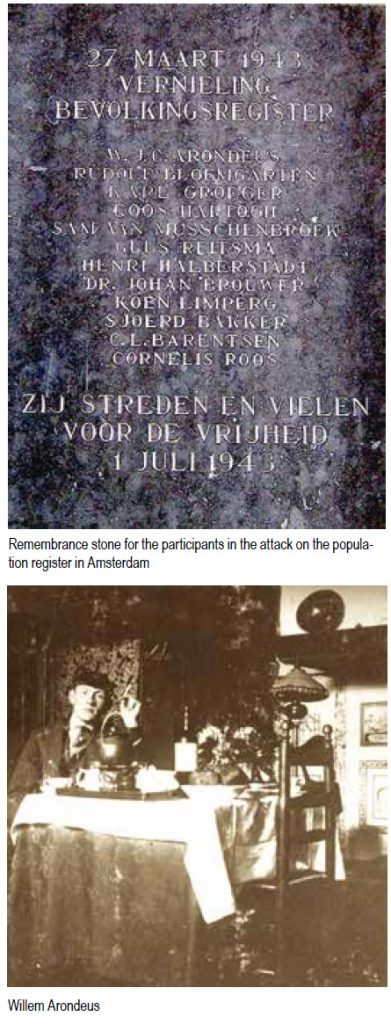

The men were quickly captured, betrayed by an anonymous source. 12 received the death penalty on June 18, 1943. Two weeks later, on July 1, they were taken to a site on the Overveense dunes. Handcuffed and without blindfolds, they faced a firing squad using submachine guns. Two others were deported to the Dachau concentration camp near Munich, which they survived. Van der Veen avoided capture until the next year, when he too was arrested and shot.

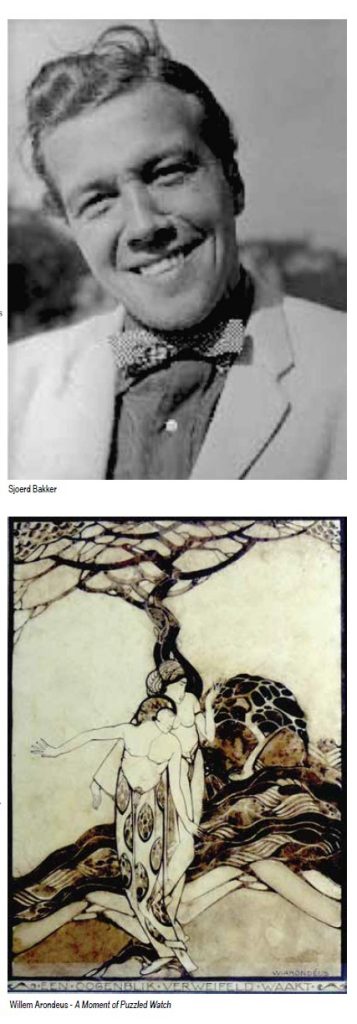

Among those executed was Sjoerd Bakker (1915–1943), a tailor, cutter, and fashion designer. Like Arondeus, a close friend, he was openly homosexual. It was he who fabricated the police uniforms used on March 27. Just before his execution, the Nazis allowed him to make a single request. He asked to wear his favorite pink shirt, which became his shroud. After the war, it helped to identify him and his colleagues in their unmarked mass grave.

Also deeply involved in planning the Public Records Office offensive was Dutch musician Frieda Belinfante (1904–1995), who could not be there: there were no women on the Amsterdam police force. A well-known and highly respected cellist and a pioneering female conductor, she made no secret of her loving women. When she was 18, she met Henriëtte Bosmans, an upcoming pianist. Their relationship lasted for 6 years.

After the exploits of March 27, Belinfante first hid out in Amsterdam, disguised as a man. “I really looked pretty good,” she later said. The Dutch Resistance then smuggled her out of the country to Belgium and into France, where the French Underground helped her to reach Switzerland, which at first refused her asylum. Only after a Swiss friend confirmed that she was, in fact, a Dutch citizen was she allowed to stay.

The Swiss repatriated Belinfante to the Netherlands soon after the war ended in 1945. She moved to the United States two years later, teaching music at UCLA, giving private lessons, and playing for Hollywood studio soundtracks. In 1954 she became the founding artistic director and conductor of the Orange County Philharmonic, making her the first woman to be the permanent conductor of a resident professional orchestra.

None of these defenders of humanity was defeated by fascism’s brutality. They had defied oppression and shown others how to fight it. For Arondeus especially, the effort had been worth the sacrifice. “Death has no horror of any of us,” he wrote to a friend. “I go with a grateful heart.” To the end he remained true both to his principles and to himself.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on November 5, 2020

Recent Comments