By Gary Kramer–

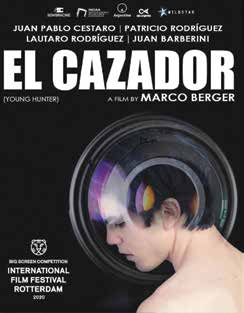

Out gay Argentine filmmaker Marco Berger applies his patented style—long, lingering, homoerotic shots of two guys, more silence than dialogue—to a kind of thriller narrative in his provocative new film Young Hunter, available October 27 on DVD and streaming.

This hypnotic drama opens with 15-year-old Ezequiel (Juan Pablo Cestaro) hanging out with a classmate from school. He studies his friend as they play a video game, and he quietly ogles him lounging around the pool. As they peruse a porno magazine, Ezequiel makes a pass at his buddy, who insists he is not into boys. Soon after this rejection, Ezequiel catches the eye of Monos (Lautaro Rodríguez), a sexy, tattooed, and slightly older boy he admires at a skatepark. Ezequiel invites Monos over and slowly a potential romance develops.

Young Hunter is very much about seduction, but not quite in the way viewers might expect. Berger is slowly developing a sinister atmosphere—as cued by the music and camerawork. (One fantastic shot has the camera titling 90 degrees as Ezequiel is emotionally devastated.)

Given that Ezequiel is a gay 15-year-old, horny, and home alone—his parents and sister are away for a few weeks; his aunt checks in on him every three days—there is ample opportunity for him to find trouble. Berger plays up this danger as Monos and Ezequiel become closer and spend more time together. When they arrange a sleepover at Monos’ cousin Chino’s (Juan Barberini) house, the youths plan to have sex when Chino is not around. However, after their night of passion, Monos grows distant, and Ezequiel becomes forlorn. What is more, at this point in the story, Young Hunter reveals what it is really about—a blackmail plot that puts Ezequiel in a very uncomfortable position. Viewers will also squirm given what transpires.

That may already be disclosing too much, and it would spoil the film’s tension to reveal more. Berger lets viewers absorb the situation Ezequiel finds himself in by shifting the narrative to focus on Juancito (Patricio Rodríguez), a baby-faced 13- year-old who befriends Ezequiel. (They first meet when he bums a cigarette off Ezequiel.) Juan is, like Ezequiel, quietly exploring his own attractions, but their friendship is creepy given Juancito’s youth. Nevertheless, Berger truthfully captures the infatuation a younger gay teen has for a slightly older boy.

Viewers will likely feel conflicted and unsettled as Young Hunter plays out. Ezequiel makes some questionable decisions that will likely prompt a loss of sympathy for this otherwise likeable teen who is confronted with a difficult situation. Berger takes a calculated risk here, but his skill as a filmmaker delivers a satisfying payoff.

One of the strengths is Cestaro’s performance, which involves him looking, but not speaking, through much of the film. A scene of Ezequiel and Monos quietly sitting conveys so much without dialogue. The young actor, in his feature film debut, communicates his desire and despair through his expressions, especially when he is drifting off in a classroom or at home. He is so perfectly vulnerable, especially regarding his love for Monos, that he transfers those emotions—consciously or not—to Juancito.

But he also has another agenda, which weighs on him heavily, freighting his every move and his every exchange with deeper meaning. Ezequiel is young and impressionable, and when his naiveté is exposed, he feels wounded. Cestaro makes that aching palpable.

Berger is masterful in keeping things ambiguous, and a scene that feels like it could be a dream is real, while a scene that feels real turns out to be a dream. He also provides uneasy answers when Ezequiel and Chino have a discussion about Monos and other things.

Young Hunter, like many of the director’s films, throbs with sexual tension. Berger emphasizes the attraction Ezequiel has for his classmate and for Monos in how he shoots male bodies. The camera doubles as Ezequiel’s eyes when he admires his classmate, Monos, and even Chino in various stages of undress with a shameful lust. Likewise, when Juancito is seen contriving an opportunity to glimpse at an older man he knows in the shower, the parallels between the two youths is prominent.

Young Hunter is discomfiting with its focus on gay teenage sexuality, but it absolutely acknowledges the insidiousness of youths, gay or straight, being exploited. Berger carefully walks a very fine line—as he did in his award-winning film Absent nearly a decade ago. (In that film, a teacher allowed a student to stay at his apartment, only to have complications arise as a result.) There are scenes in this new film that are suspect, but Berger includes them to provoke and confront. This story is uncomfortable, but it needs to be told—and seen.

© 2020 Gary M. Kramer

Gary M. Kramer is the author of “Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews,” and the co-editor of “Directory of World Cinema: Argentina.” Follow him on Twitter @garymkramer

Published on October 21, 2020

Recent Comments