By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

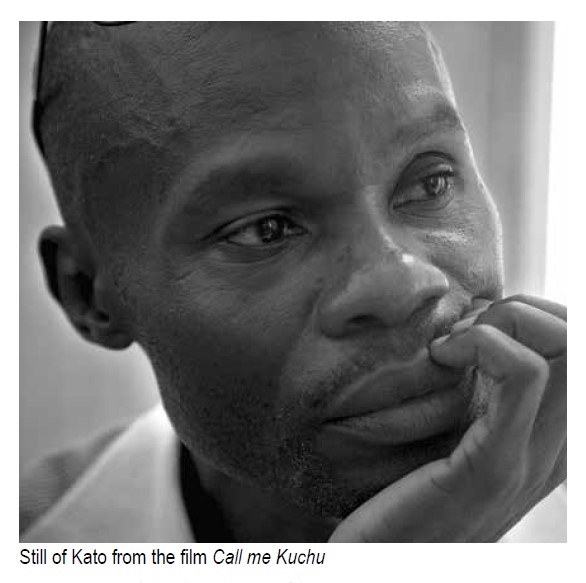

Described by The Economist as “Uganda’s first openly gay man,” David Kato is considered to be the father of the Ugandan LGBT rights movement. In a country where same-sex intimacy is both illegal and dangerous, he was out and visible. “If we keep on hiding,” he said, “they will say we’re not here.” Fired from teaching jobs, maligned in the media, arrested three times just for being himself, “his selfless dedication to defending human rights and speaking out against injustice” led to his murder when he was 46 years old.

One of the Kisule people of Central Uganda, Kato was born in their ancestral village of Nakawala in 1964—the exact date is not known. He attended the prestigious King’s College Budo, located very near Kampala, the nation’s capital, and Kyambogo University, now one of Uganda’s largest public universities. He became a teacher, eventually taking a position at the Nile Vocational Institute in Njeru, where he realized his sexual orientation. Gay people were not welcome at the school, so governance fired him in 1991.

A few years later, Kato moved to Johannesburg, South Africa, just when the country was trying to transform from apartheid to a multicultural democracy. Witnessing the struggle up close changed him forever. “I fought for their liberation,” he said later, “so when I came home—that was in 1998—I had the same momentum. I tried to liberate my own community.” Already living quietly as a gay man, he now acknowledged his homosexuality in the most public way possible: a press conference in Uganda’s capitol city.

Being openly gay in Uganda was then, and still is, illegal and dangerous, so Kato’s admission was historic, unprecedented, shocking. Not only was he the first Ugandan to voluntarily announce his gayness in his home country, but he also was defending LGBT people publicly.

The authorities were not pleased. Almost immediately he was arrested and beaten by police, then detained in jail for a week without charges. Undeterred, he quickly became one of the nation’s most visible campaigners for human rights.

In 2004, Kato helped to co-found Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG), and then became the organization’s advocacy and litigation officer. “My work mostly is to document violence and cases of discrimination,” he explained, but he also wanted to bring people together. “When we came out, we knew it alone, and we suffer it for many years. But the minute you find, ‘ah, this one is like me, so we are brothers, so we are friends, so we are partners in the struggle.'”

In October 2010, the Uganda tabloid Rolling Stone (with absolutely no association with the U.S. periodical of the same name), published a page one article titled “100 Pictures of Uganda’s Top Homos Leak.” It included the names, photographs, and addresses of LGBT Ugandans, with a yellow banner reading, “Hang Them.” The story was denounced by human rights organizations around the world. Even so, the publisher, 22-year-old Giles Muhame, continued his campaign of vilification with “More Homos’ Faces Exposed” in the next issue.

Kato and three other members of SMUG, whose names and images had appeared in the tabloid, immediately petitioned the High Court of Uganda to force a halt to distribution of the article. The court granted the request on November 2, 2010, then issued an interim order restraining the editors of the newspaper from publishing information about anyone alleged to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender until the case could be finally determined. The following January, it ordered the paper to shut down completely.

Less than three weeks later, Kato was brutally murdered in his apartment by an intruder who beat him to death with a hammer. Police initially said that the motive was robbery, but later implied Kato was killed because he would not pay his assassin for “sexual favors,” essentially blaming the victim for his fate.

At his trial, his murderer gave a third explanation: using the notorious “gay panic” defense. He claimed Kato propositioned him to perform illegal acts. Found guilty, he was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Colleagues and friends disputed all three explanations. As the most outspoken LGBT rights advocate in Uganda, a country where homophobia is so severe that Parliament at the time was considering a bill to execute gay people, Kato had received a stream of death threats, they said, and he was not alone. Others mentioned in the Rolling Stone article had been attacked; many, fearing for their lives, were in hiding. They believed that Kato was killed because of his prominence and his lawsuit against the tabloid.

Even in death, however, those who hate would not let Kato rest in peace. After the murder, Muhame, sincerely or not, expressed his sympathies for Kato’s family, but also stated that he believed his paper was not responsible. “I have no regrets about the story,” he said. “We were just exposing people who were doing wrong.” The human rights activist, it seemed to him, “brought death upon himself. He hasn’t lived carefully. Kato was a shame to this country.”

Others were even more extreme in their comments and their behavior, continuing to hound and harass Kato for his sexuality and for being his true self in life. By the time the local Anglican priest rose at his funeral to deliver the final homily, he understood that Kato and many of the mourners present were LGBT. Unable in his mind “to bless in Christ’s name” an “unrepentant sinner who had defied God to the last,” he preached that Kato was going to hell.

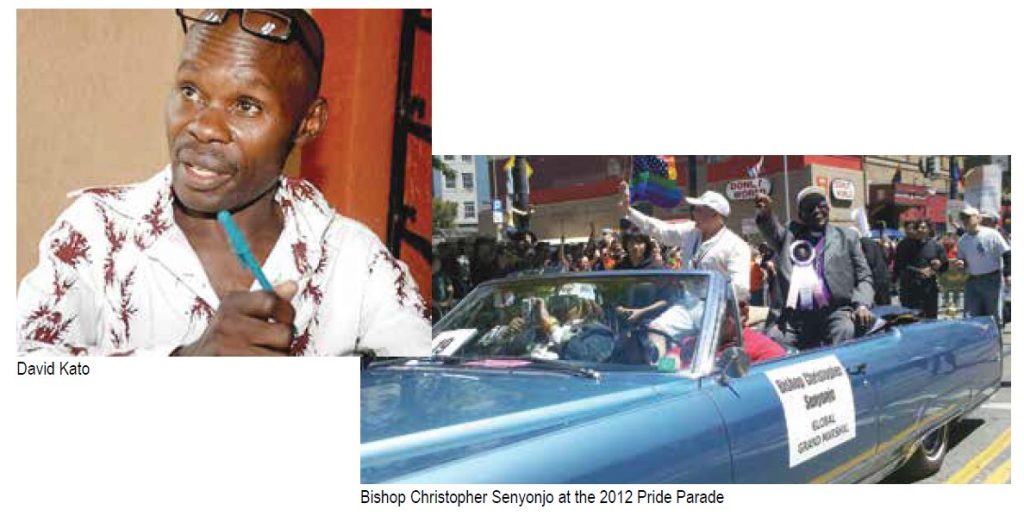

Not until the mourners gathered at graveside, however, did they receive words of comfort and truth, which came from the Anglican Bishop Christopher Senyonjo, who 10 years earlier had been barred by the Church from performing services because of his steadfast support of LGBT Ugandans. “God loves you, Kato.” he said. “He knows you. He brought you into the world. And you have done your work. So, rest in peace.”

In 2012, Senyonjo was celebrated as San Francisco Pride’s Global Grand Marshal. As for Kato’s legacy, the Legacy Walk in Chicago features a plaque honoring him. This year, the University of York in the U.K. will be naming its newest college the David Kato College, marking a rare and perhaps unprecedented naming of a college after an openly LGBT individual.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on January 13, 2021

Recent Comments