By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

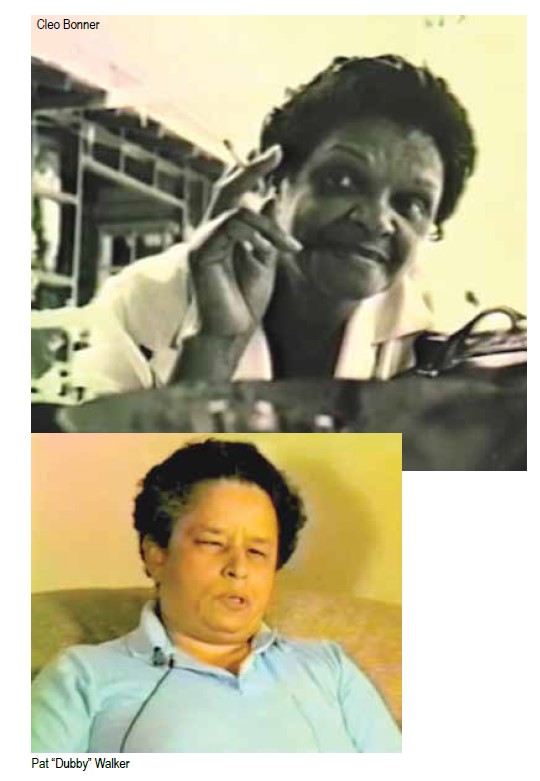

Pat ‘Dubby’ Walker

Pat “Dubby” Walker had not heard of the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) until Billye Talmadge, one of the organization’s co-founders, visited Oakland’s Orientation Center for the Blind in 1958. “She picked me out as gay,” Walker remembered. “She started taking me to different things” and introduced her to many of the women involved in the organization. “There were parties, picnics, getting together to work on [The Ladder],” the group’s monthly publication.

Two years later she became the first Black president of the San Francisco chapter.

Needless to say, the world of 1960 was very different from today. Homosexuality was illegal in all 50 states, including the two newest, admitted to the Union only the year before. By executive order of then-President Dwight Eisenhower, anyone working for the federal government discovered to be homosexual was fired immediately; no known gay men or lesbians could be hired and they had no legal protections anywhere. In San Francisco, police often arrested people simply for touching someone of the same sex, claiming lewd conduct or worse.

“Dubby,” born on February 18, 1939, had four strikes against her succeeding in that world. Black, female, blind, and lesbian, she was fortunate in one way, at least: a sympathetic and supportive home life. “When I was eleven or twelve, my mother told me about gayness,” she shared with an interviewer in 1988. “My mother had gay friends and my sister is also gay. At fourteen I realized I liked girls. I never felt bad about myself because of it.”

Determined to live an independent life, Walker learned “how to use her other senses to ‘see’ her way.” She refused a guide dog. “They get all the credit,” she said. She supported herself first with a telephone wake-up service, then by operating a convenience shop in the lobby of a downtown Berkeley office building. No disadvantage or disability, Del Martin wrote later, “stopped her from being an activist and making the world a better place for women, lesbians, African Americans, and the blind.”

In 1964, Walker was one of five representatives of the DOB at a retreat in Mill Valley that hoped to establish “better understanding between homosexuals and organized religion.” The result: the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH), “the first group in the U.S. to use the word “homosexual” in its name.” While actively working to let gays and straights alike know that “Gay is Good,” it became an important source of legal and political support for San Francisco’s LGBT communities.

Cleo Bonner

Cleo Bonner, the first Black national leader of the Daughters and the first woman of color to lead a national LGBT organization, also was at the retreat. She had joined the DOB four years before, in 1960, already in a committed relationship with a woman, raising a son, and working at Pacific Bell, which some years later admitted that “we do not knowingly hire or retain … homosexuals.” To protect herself and her family, she became known as “Cleo Glenn.”

Not only did she almost immediately take on the job of circulation manager for The Ladder, but she also with her partner ran the DOB’s Book Service at a time when “education of the variant” and “education of the public” were among the organization’s most important goals. Women now could access information, literature, and novels about lesbians that were “well-written and ending happily,” and music—“the gayest songs on wax”—they dared not ask for and often could not find where they lived.

In June 1964, Bonner travelled to New York with Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin to attend the DOB’s third national convention, themed “The Threshold of the Future.” She had been elected to the organization’s national governing board in 1961, was appointed acting president two years later, and elected president in 1964. Welcoming the delegates, she acknowledged, “We have our struggles and disappointments,” although the convention itself was “quite a world-shaking event.” She encouraged everyone to “go on a little longer, to help where we can and do what we can.”

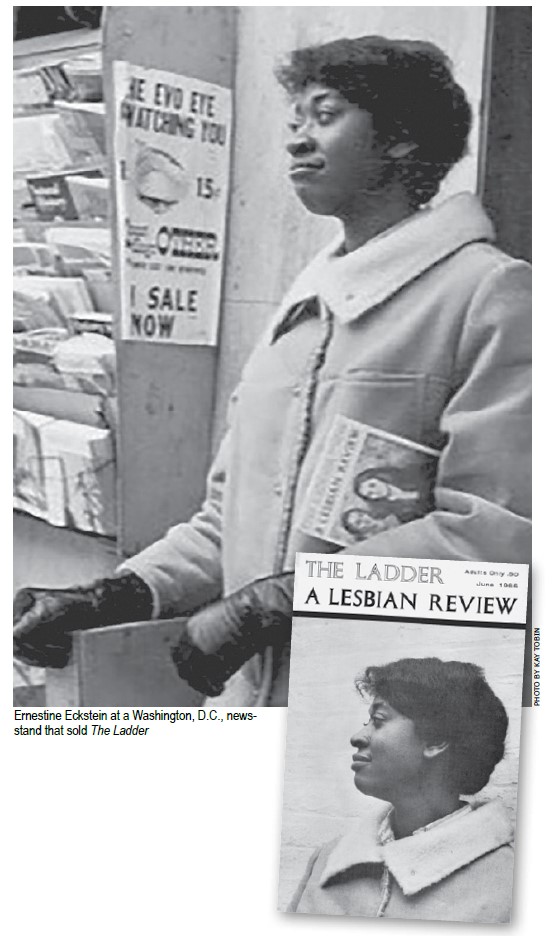

Ernestine Eckstein

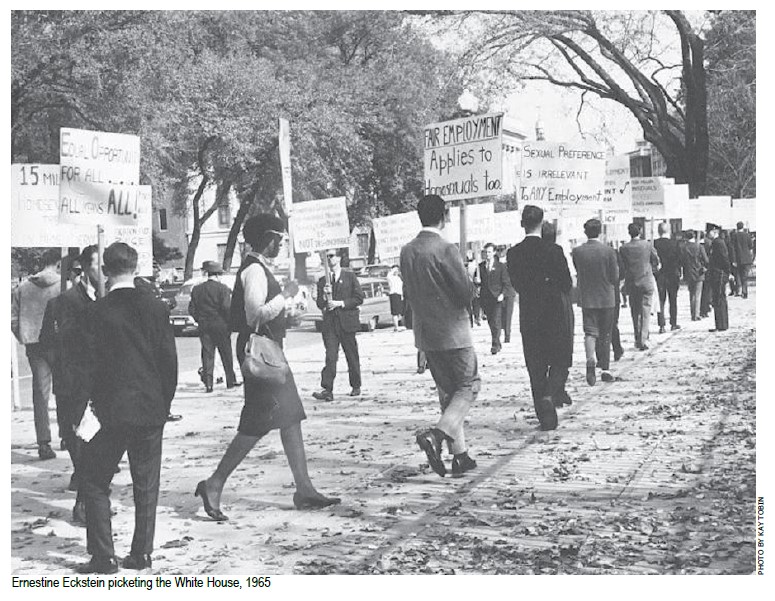

Bonner’s term as national president ended in 1966, the year that Ernestine E,ckstein, vice president of the DOB’s New York chapter, became one of two Black women to appear on the cover of The Ladder. Like Bonner, she dared not use her true last name, but unlike Bonner and many of her peers, she wanted to do more than “help where we can.” She saw the value of protests and demonstrations and was willing to be seen picketing, very visibly, even in front of the White House.

Although only two years younger than Walker, Eckstein belonged to a new generation, one that believed public activism, not education and cooperation, was the best way to bring about society’s acceptance of gay men and lesbians. As an undergraduate at Indiana University, Bloomington, she was involved in her local NAACP chapter. After moving to New York, she joined the Mattachine Society, the DOB, and the Congress of Racial Equality, which “pioneered the use of nonviolent direct action in America’s civil rights struggle.”

For Eckstein visibility, which many in the homophile movement for very real reasons found threatening, was key. “Homosexuals are invisible, except for the stereotypes,” she told Kay Tobin and Barbara Gittings (who were with her at the White House demonstration) in a lengthy interview in The Ladder‘s June 1966 issue, “and I feel homosexuals have to become visible and to assert themselves politically. Once homosexuals do this, society will start to give more and more.”

She continued, “The discrimination by the government in employment and military service, the laws used against homosexuals, the rejection by the churches” had to be confronted openly. “The homosexual has to call attention to the fact that he’s been unjustly acted upon.” Demonstrations, she said, “are one of the very first steps toward changing society.”

Where Walker and Bonner had ably implemented the DOB’s original stated purpose of educating women, the public, researchers, and legislators to affect change, Eckstein now heralded the future course of the LGBT civil rights movement.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on February 10, 2022

Recent Comments