By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney

By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney

When John attended his 40th high school reunion in Kansas City last fall, it dawned on him that he and his classmates started kindergarten in early September 1963, less than a week after Martin Luther King delivered his renowned “I Have a Dream Speech” at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. In his address, King famously dreamed that his “four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character” and that one day, even in Alabama, “little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”

Despite the many times John had heard the speech, it suddenly hit him that the great civil rights leader had been dreaming about little five-year-old kids like us—our generation. As we approach this weekend’s annual commemoration of King’s birthday, we can only imagine how troubled the visionary might be if he were alive today. King’s words 54 years ago have striking relevance in January 2017, as Americans dedicated to racial, gender, LGBT, immigrant, and economic justice and equality face grave threats and uncertainty.

In 1963 King told it like it was. Reflecting on the fact that Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation a century before, King observed: “[O]ne hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.” Over a half century later, the essence of King’s message rings disturbingly true—even though significant improvements have taken place and the particular problems of today differ from those of 1963. And today, economic disparity evidenced by the vast number of Americans living on an “island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity” is reaching a crisis point.

But King did not merely describe problems; he issued a call to action—a charge that still inspires today. King declared: “We have … come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of Now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism … . It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment.”

Later this month, millions of Americans will travel to the nation’s capital for the Women’s March on Washington. Five decades ago, King warned that “those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual” and proclaimed that “1963 is not an end, but a beginning.” 2017 must be a beginning, too.

King also spoke unapologetically of hope and articulated a long-term vision of how he wanted the world to be. King implored: “Let us not wallow in the valley of despair … . [E]ven though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream … . I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'”

We in the LGBT community know well the extraordinary value of dreaming, even in the darkest hour. When LGBT Americans routinely faced disapproval and hatred that forced them to live in secret or in denial, we dared to dream of a future in which we could live openly. We came out. When we faced the worst of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, we dreamed of a day when the disease would not ravage our community. We cared for each other and took ownership of our health care in ways never seen before. Even as the law permitted states to imprison people for being gay, we dreamed of a day when we could marry the person we loved and celebrate all aspects of our love. We achieved nationwide marriage equality. As we face today’s ongoing challenges, we must keep dreaming.

Although King summoned people to stand up fearlessly and nonviolently for their rights and dignity in the face of those who opposed them, his ultimate dream was one of unity—finding shared values and respect and ending divisions, not exacerbating them. He urged, “Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.” He noted the presence of “many of our white brothers” at the march and reminded everyone gathered, “we cannot walk alone.” In the dynamic climax to his speech, King dreams of the “day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

This King weekend, we wish that King’s vision had already become a reality. But we’ll be sporting our “Don’t Let the Dream Die” buttons—and we won’t take them off until the great visionary’s prophecy comes true.

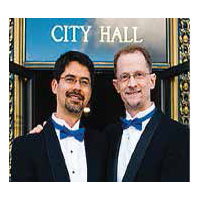

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the nationwide grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Recent Comments