By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

Charles Warren Stoddard, San Francisco’s lavender “boy poet,” made his first journey to Hawaii in 1864 when he was 21. One afternoon, “lounging at Whitney’s bookstore” in Honolulu, “fumbling the shop-worn books,” he saw “a slender but well-proportioned gentleman [enter], clad in white linen raiment, spotless and well starched.” However likeminded men know each other, Stoddard discerned that “there was something about him which would have caused the most casual observer to give him a second glance—a mannerism and an air that distinguished him.”

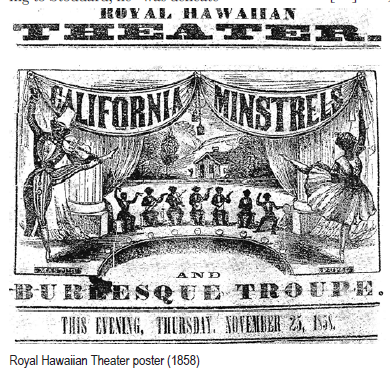

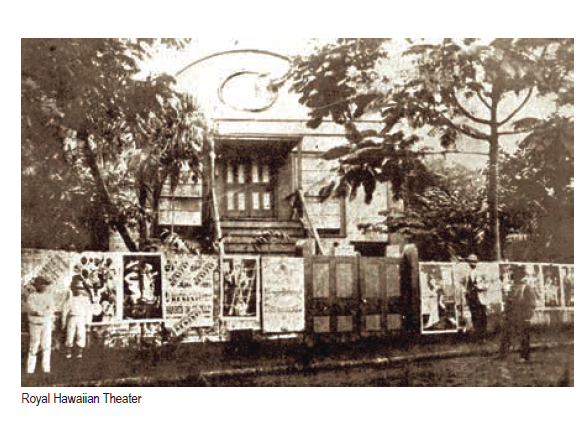

A few moments later, “upon the entrance of a common friend,” he made the acquaintance of Charles Derby, “proprietor and manager of the Royal Hawaiian Theater, likewise government botanist and professor of many branches of art both sacred and profane.” After “having cautiously exchanged a few languid commonplaces,” Derby asked Stoddard if he would like to see the playhouse. Invitation accepted, “We at once repaired to the theater, threading the blazing streets together under a huge umbrella of dazzling whiteness, held jauntily by my newfound friend.”

The two men soon discovered that they had many interests in common, including a love of theater, cluttering bric-a-brac and curiosities, travel, music, and men, a fact Stoddard could not mention, but hinted at it with detail that no one else would have shared or even noticed—and in ways that only the likeminded would recognize. “As a youth,” according to Stoddard, he “was delicate and effeminate,” a “highly imaginative dreamer, and romantic in the extreme.” As an adult, “Though not handsome he was well proportioned and possessed of much muscular grace.”

Stoddard offered other insights into Derby’s nature when he lauded his hospitality and generosity. “Many strange characters found shelter under [his] roof,” he noted. “Thespian waifs thrown upon the mosquito shore, who, perhaps, rested for a time, and then set sail again; prodigal circus boys … deserted by their fellows, here bided their time [until they] at last, falling in with some troupe of strolling athletes, have dashed again into the glittering ring with new life, a new name, and a new blaze of spangles,” among others.

Derby was born in 1826 to a wealthy and prominent family of sea captains and merchants in Salem, Massachusetts. He left home “at an early age” and “was for some years a wanderer” before joining Lee & Marshall’s Circus during the 1850s as an acrobat. He “learned to balance himself on a globe, to throw double summersaults, and to do daring trapeze-flights in the peak of the tent,” although he became best known for “an acrobatic routine using elastic cords.”

Eventually, “growing weary of this, and having already known and become enamored of Hawaii, he returned to the islands, secured the Royal Hawaiian Theater, and began life anew.” As the establishment’s owner and proprietor and manager, Derby presented everything from Chinese circuses to ventriloquists, spiritualists, magicians, dance troupes, plays, and melodramas, a troupe of trained poodles, concerts, bell-ringing exhibitions, and grand opera. The most popular entertainment, however, was blackface minstrelsy.

Derby not only managed the theater, but he also appeared in some of its productions. “Nothing seemed quite impossible to him on the stage,” Stoddard wrote. “Anything from light comedy to eccentric character parts was in his line; the prima donna in burlesque was a favorite assumption; nor did he, out of love of his art, disdain to dance the wench dance in a minstrel show.” His reputation as an expert female impersonator, however, did not raise questions about his masculinity, at least publicly.

Hawaii’s missionary community disdained the theater—“one of his Satanic majesty’s traps to lead men to perdition”—but praised Derby for another one of his enterprises: the gymnasium he opened in the theater’s auditorium when it was not being used for performance. While the theater might promote “indolence, drunkenness, and rioting,” the need for physical education apparently was very great. “All you flaccid muscled, round shouldered, bilious-eyed clerks and shopmen,” the Pacific Commercial Advertiser editorialized in 1859, “go to Derby and get a new lease of life and health.”

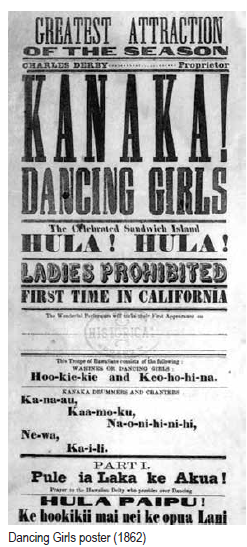

Unlike many Americans living there, Derby respected the people of Hawaii and their culture. He learned the language of the islanders, which the missionaries were trying to suppress, and sought to promote their time-honored heritage and traditions, which the missionaries were trying to ban outright. Attempting to bring traditional chant and dance to the public, he organized a hula troupe, which included two female dancers and five male drummers, to tour California in 1862, “the only ones who have gone abroad professionally,” wrote Stoddard.

Sadly, their tour was not a success. The men who attended the performances—women were not allowed—evidently expected a sensational or even risqué exhibition, but onstage the dancers dressed conservatively—none wore a grass skirt—and maintained their decorum always. Not discouraged, after they returned to Honolulu, Derby staged the city’s first recorded public presentation of the hula at his theater. The missionaries condemned it as a “shameful exhibition,” but within a decade, Hawaiian dance became popular with audiences.

Derby made other lasting contributions to life on the islands. He gave music lessons and also instructed his students in the social graces of dancing and the manly arts of fencing and boxing. More importantly, he opened a nursery, imported non-native species—something not allowed now—and sold them to gardeners throughout the city. Including palm, eucalyptus, and cinnamon camphor trees, scarlet bougainvillea, and jade plants, they became an enduring part of Hawaii.

In 1878, when the Pacific Commercial Advertiser announced that Derby would be leaving the islands, it cited his great contributions to “the recreation of the public,” his “knowledge of botany” that “has assisted many in the successful introduction of plants and flowers,” his gymnastic classes, and “his abilities as a teacher of music.”

He returned to his hometown in Salem, Massachusetts, where he died in 1883, but his legacy, especially in the ways he reshaped Hawaii’s landscape, endures.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on February 23, 2023

Recent Comments