By Gary M. Kramer–

The lukewarm slow burn thriller Eileen, opening December 8, is set in 1960s Massachusetts, where the 24-year-old title character (Thomasin McKenzie) lives with her dad (Shea Whigham), an alcoholic retired cop. Eileen works in a prison for boys, and her life is pretty unexciting. She spends her time driving to the beach, having sexual fantasies, and binging on candy. The clouds of smoke her car belches through its vents are an apt metaphor for her gray, hazy life.

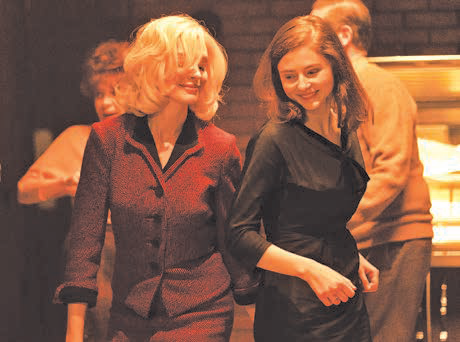

However, things change, dramatically, when Rebecca (Anne Hathaway), the new prison psychologist, arrives in a red convertible. Fabulously dressed, and sporting dazzling blonde hair, Rebecca has an attitude like spiked heels; she attracts attention but doesn’t care what people think. Moreover, she sees Eileen, whom she says “has gumption,” as a kindred spirit. Their initial meetings percolate with some mild sexual tension, and things really begin to simmer when Rebecca asks Eileen out for a drink one night.

A sequence of the two women at a local bar, having a cocktail and then dancing together, is pure romance for Eileen. The ways Rebecca handles a guy who tries to cut in on them are impressive. A kiss Rebecca gives Eileen at the end of the evening only prompts the young woman to go back in the bar and finish off the cigarette butt Rebecca left in the ashtray.

Eileen, directed by William Oldroyd, makes Rebecca an enigmatic beauty, and surely she is up to something. And Rebecca does find Eileen, whom she describes as “plain but fascinating,” as having a “beautiful turbulence.” The film builds up the connection between these women with Eileen sneaking into Rebecca’s office at work and having fantasies about her comely new colleague.

But Eileen has other fantasies, including sexual ones about a guard (Owen Teague), but also violent ones that involve the use of a gun. Oldroyd sprinkles a handful of dream sequences into the film to keep viewers off kilter and express what Eileen is thinking. These episodes, however, are cheap and gimmicky. It is pretty clear how much Eileen dislikes her father’s treatment of her— he consistently makes her feel bad — that her imagining shooting him in the head is, well, overkill.

Prior to Rebecca’s arrival, Eileen was fascinated by Lee Polk (Sam Nivola), a boy who was imprisoned for murdering his father. Rebecca develops an interest in Lee’s case as well, inviting the boy’s mother (Marin Ireland) to a meeting with her son that goes badly. But Eileen and Rebecca’s interest in Lee’s crime guides the film’s third act, which takes a turn that viewers likely won’t see coming—unless they have read Ottessa Moshfegh’s source novel. (Moshfegh and her husband Luke Goebel adapted her book for the screenplay.)

McKenzie plays Eileen with the right mix of innocence, wonder, and desire. She can be assertive at work, or with her father, but she can also be naïve, especially as Rebecca draws her in by complimenting her and boosting her confidence. Eileen’s behavior is also odd, as when she pulls faces in Rebecca’s bathroom mirror out of anxiety. Her infatuation with Rebecca could be attributed to the fact that someone paid attention to her than any latent same-sex desire. Eileen is mysterious, but her character does not engender much emotion, which is necessary for the film to succeed; at times Eileen feels as lifeless as her character.

In contrast, Hathaway is convincing in the femme fatale role, and she knows exactly how to play up Rebecca’s seductiveness. The film provides some real pleasure when she shows off a nifty trick that she learned for opening a wine bottle without a corkscrew. Rebecca also drips with innuendo when she tells Eileen, “People are so ashamed of their desires,” or, “I live a little different than most people. I have my own ideas … . Maybe we share some of those.” It is a tease, and Hathaway makes these lines alluring before she reveals what she is actually up to.

Oldroyd’s deliberate approach holds interest intermittently up to the twist that puts Eileen in a moral quandary. Eileen’s love for Rebecca motivates her to participate in what is, in fact, a crime, and the film will polarize viewers with its last act because it is difficult to care about the characters given their rash decisions. Eileen certainly plants several seeds to indicate that its title character may not be the “good girl” everyone thinks she is. But as the story plays out, what unfolds becomes hard to swallow.

That said, the film is impeccably well lensed, with an appropriately burnished color palette. A lengthy scene of Eileen staring out the window is so beautiful (and heartbreaking) that it resembles an Edward Hopper painting. In contrast, the film’s soundtrack also feels very on the nose, especially when a song, heard early in the film, features the lyric, “How bad I am.”

Eileen is a not uninteresting character study, and there are some compelling scenes. But ultimately it fails to stick the landing. This story may have worked better on the page.

© 2023 Gary M. Kramer

Gary M. Kramer is the author of “Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews,” and the co-editor of “Directory of World Cinema: Argentina.” He teaches Short Attention Span Cinema at the Bryn Mawr Film Institute and is the moderator for Cinema Salon, a weekly film discussion group. Follow him on Twitter @garymkramer

Film

Published on December 7, 2023

Recent Comments