By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

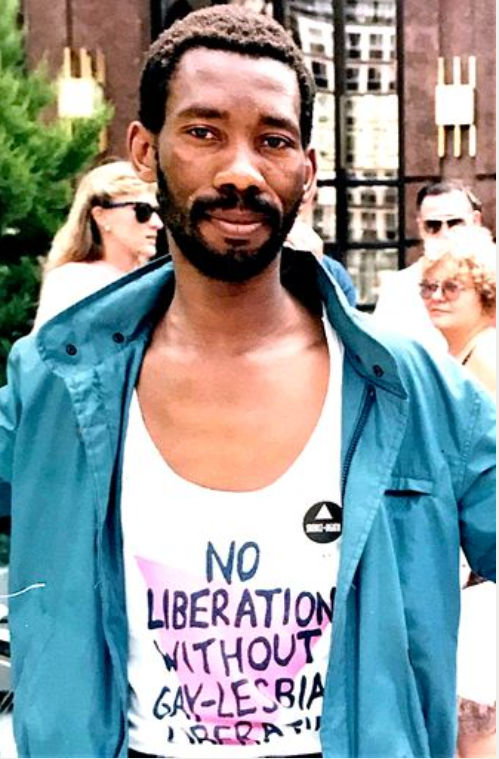

When Simon Tseko Nkoli was born in Soweto, South Africa, on November 26, 1957, everything about his future was determined by a brutal apartheid government that enforced a rigid system of segregation and oppression: where he could live, what he could learn, whom he could love. Described by The Sunday Times, South Africa as “the founder of the Black gay movement” in his country, “he put his body on the line and his destiny in the public eye” to win human rights for all.

Nkoli came to clearly understand the injustices faced not only by Black women and men under laws enforced by his country’s unjust political and social system, but also by all people marginalized for being who they are. He often told the story of how, at age nine, he locked his parents in a clothes closet to evade police who were enforcing the pass laws, which severely restricted the lives of Black South African and other racial groups by confining them to specific, designated areas.

The experience left a powerful impression on him that he later shared as a metaphor for anyone living a closeted life under a regime that oppressed its citizens, not only because of their race, but also because of their religion, gender, and sexuality. “In so many ways,” he wrote in a memoir published in Defiant Desire: Gay and Lesbian Lives in South Africa, “the closet I have come out of is similar to the wardrobe my relieved parents stepped out of when I unlocked them after the police left.”

His was a sad truth. “If you are Black in South Africa, the inhuman laws of apartheid closet you. If you are gay in South Africa, the homophobic customs and laws of this society closet you. If you are Black and gay in South Africa, well, then it really is all the same closet, the same wardrobe. Inside is darkness and oppression. Outside is freedom. It is as simple as that.” Believing a democratic society had to embrace all its citizens, he had a goal to open every closet door.

Nkoli met his first lover, Andre, a white bus driver, when he was 19. The families of both men opposed the relationship. Andre’s parents accepted their son’s homosexuality, but rejected a Black man as his lover. Nkoli’s mother refused to accept his sexual orientation, taking him on what he described as a “year-long tour of the sangomas [traditional healers of Southern Africa] of Sebokeng,” where they lived then, “to find the causes of his so-called bewitchment.” They also visited a priest, who quoted Bible verses to him, and a psychiatrist.

Eventually his mother accepted his orientation, but there was yet another barrier to their relationship: in their segregated society, a Black man and a white man could not live together as equals in either a white neighborhood or a Black neighborhood. Here serendipity provided the solution. The psychiatrist Nkoli’s family took him to see, himself a gay man, suggested that Nkoli simply pose as Andre’s servant. The result created yet another closet—legally they could not live anywhere as a gay couple—one more discrimination to end.

Nkoli’s life of activism began in 1976 with protests against his government’s stark racist policies; he was arrested four times. In 1979, he became a member of the Congress of South African Students (COSAS), which opposed apartheid. Soon after he joined the mostly white Gay and Lesbian Association of South Africa (GASA), although the group refused to support his activism against the government’s racist policies. What he hoped for was an organization that would fight both Black and LGBT suppression.

In 1984, Nkoli participated in a protest march in Sebokeng organized by the United Democratic Front (UDF) that led to 22 arrests, including his. During what became known as the Delmas Treason Trial, the prosecution tried to prove that the UDF, a coalition of anti-apartheid grassroots and community organizations, was working with the banned African National Congress (ANC), which the governments of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan also had condemned as a terrorist organization, to overthrow the state by violence.

Nkoli remained in detention for nine months before being formally charged with treason, a crime punishable by death. It was two years before he was released on bail and another year and a half before he received a suspended sentence, with severe restrictions on his rights to freedom of speech and association. Another year passed before an appeals court declared the entire trial invalid and the charges against him and his co-defendants were dropped.

During his time in prison, Nkoli realized that apartheid had to be challenged for all its oppressions. Although his sexuality was not a secret, he decided to tell the other defendants that he was gay. Learning his truth, some of them asked that he be tried separately, afraid that his love of men would “further condemn them all” if he were tried together. Ultimately, he came to understand that discrimination is discrimination, whatever the reason, and decided to stand trial together.

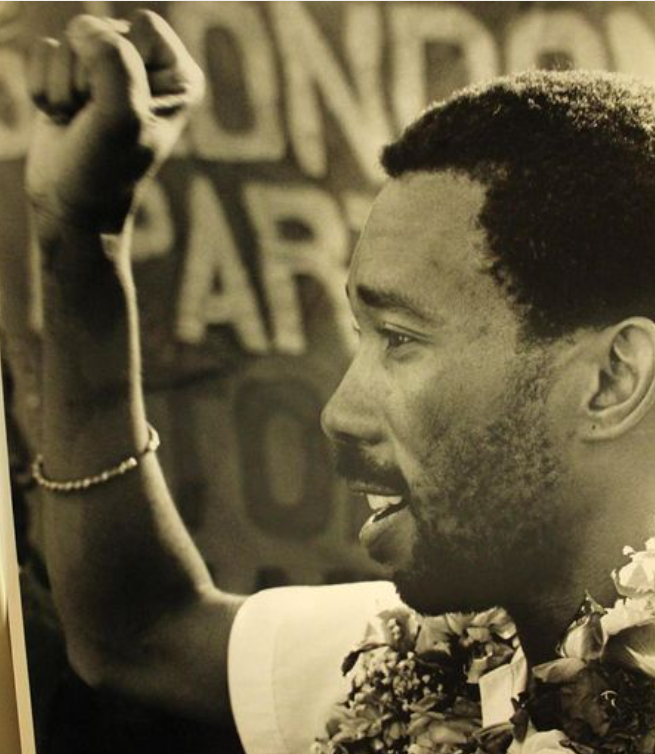

After his acquittal, Nkoli co-founded the group he had long envisioned, the Gay and Lesbian Organization of the Witwatersrand (GLOW), to fight both against racial discrimination and for human rights for LGBT people. The next year, on a world tour, he spoke about need for all oppressed people to work together, so they could guarantee freedom and equality for everyone: “If we isolate the gay and lesbian struggle it will be the same as women isolating their struggle, or the youth, or workers, and then everybody will have lots of struggles within apartheid. So, let’s bring all these struggles together, as we are doing, and united we will go somewhere.”

In 1990, Nkoli helped organize South Africa’s first Gay Pride celebration in Johannesburg. “With this march,” he said, “gays and lesbians are entering the struggle for a democratic South Africa where everybody has equal rights and everyone is protected by the law: Black and white, men and women, gay and straight.” He also co-founded the Township AIDS Project to educate gays about an epidemic made so much more devastating because of the shame, secrecy, and ignorance that still surrounded it.

With change starting to come to the nation, Nkoli began working to include a clause in a new constitution that would protect its citizens from discrimination because of their sexual orientation. Adopted in 1996, South Africa became the first country in the world to specifically outlaw discrimination against LGBT people in its Bill of Rights: “The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, color, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language, and birth.”

By then, Nelson Mandela, 11th President of the ANC, had become the country’s first Black head of state.

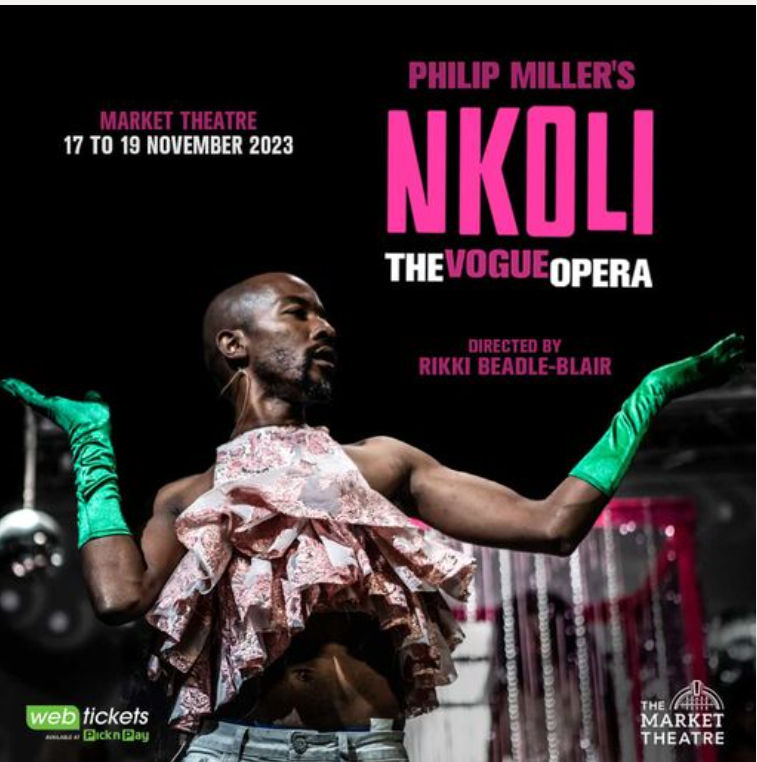

Nkoli lost his struggle with AIDS on November 30, 1998, four days after his 41st birthday. His life is an everlasting example not only for Black and LGBT people who are still fighting to be themselves in societies that refuse to acknowledge their humanity, but also for anyone striving for equality and justice in an often-unjust world. He reminds us that “the struggle for human rights knows no boundaries” and inspires us to build societies that embrace everyone.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on March 21, 2024

Recent Comments