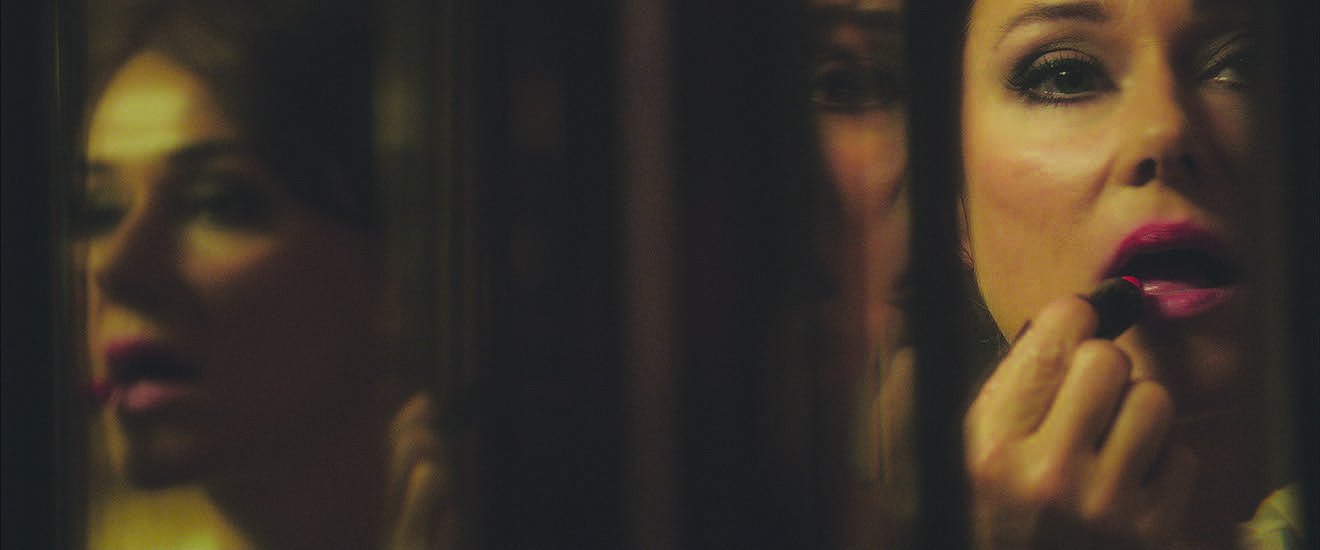

The Venn diagrams of lesbians, S&M practitioners, and lepidopterists overlap in The Duke of Burgandy, writer/director Peter Strickland’s distinctive, ecstatic, and arch romantic drama. The film takes its visual cues from 1960s and 1970s European arthouse softcore—think Radley Metzgar—and its aural cues from butterfly sounds to soap bubbles popping.

The Venn diagrams of lesbians, S&M practitioners, and lepidopterists overlap in The Duke of Burgandy, writer/director Peter Strickland’s distinctive, ecstatic, and arch romantic drama. The film takes its visual cues from 1960s and 1970s European arthouse softcore—think Radley Metzgar—and its aural cues from butterfly sounds to soap bubbles popping.

The film opens with Evelyn (Chiara D’Anna) bicycling to the home of Cynthia (Sidse Babett Knudsen). After Evelyn rings the doorbell and waits two minutes, Cynthia answers.

“You’re late,” she scowls, and brings her maid into the living room.

“Did I say you could sit?” Cynthia asks, when Evelyn positions herself on the couch.

“Did I say you could sit?” Cynthia asks, when Evelyn positions herself on the couch.

“You can start by cleaning the study,” the mistress commands, adding, “And don’t take all day this time.”

The scene is, it is revealed, a master/slave routine—there is even a notecard detailing these precise dialogue and instructions—that the women perform for their erotic pleasures. Their role playing additionally involves Cynthia denying Evelyn the opportunity to go to the toilet, as well as a “punishment” that takes place behind the closed bathroom door when Evelyn fails to hand-wash Cynthia’s panties properly. Hint: it explains why the mistress is always drinking large glasses of water.

The Duke of Burgandy plays out this and other S&M scenarios several times, and not just for the dark amusement it gives the characters and the audience. Strickland is emphasizing the power positions of the two lovers. Evelyn admits how grateful she is to be “used” by Cynthia, a woman who is all she ever dreamed about, but never thought she would find. While Cynthia is anxious to please her lover, the film shows her veneer is starting to crack.

Evelyn’s happiness is dependent upon Cynthia being unhappy about her maid skills at boot polishing, panties laundering, and house cleaning, and then chastising her for it. In bed together, Evelyn is aroused not by her lover whispering sweet nothings to her, but by Cynthia giving her a verbal spanking. When she pleads to Cynthia to use “more conviction” in her stern reprobation, it is both funny and telling. A discussion of when Cynthia can surprise Evelyn is equally comical: It should be within the next 24 hours, but not in the first hour or the last hour, Evelyn explains. So, within the next 22 hours, Cynthia inquires, drolly.

One of the film’s best sequences involves Evelyn’s meeting with a female carpenter (Fatma Mohamed). The carpenter describes a bed that allows the lovers to sleep on top of one another, noting that takes eight weeks to construct. Evelyn is disappointed at having to wait, but when the carpenter tells her about another product, a human toilet, she becomes more enthusiastic. Such moments are among the film’s charms.

That Strickland has his lovely actresses give such superb, controlled performances is what makes the film so captivating. That they rarely break character is part of the film’s fun. When Evelyn expresses disapproval about Cynthia wearing comfortable clothes, or an act of betrayal is discussed, these moments are likely a lover’s spat. However, they may be part of the couple’s role-playing. The ambiguity is quite delicious. Likewise, the film’s narrative, which repeats scenes and images and includes several hypnotic sequences—such as a one that begins and ends with the camera zooming into Cynthia’s privates—suggests various interpretations.

The Duke of Burgandy is a film is about precision that is itself precisely made. The shots of pinned butterflies underscore the dominant/submissive relation

Recent Comments