By Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis–

As a gay man, I’ve long known that many LGBTIQ people had been imprisoned in the Nazi concentration camps, and that gay men endured “unusually harsh treatment” at the hands of the Nazis who “saw them as perverts deserving special punishment” as explained by historian Nikolaus Wachsmann in KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps.

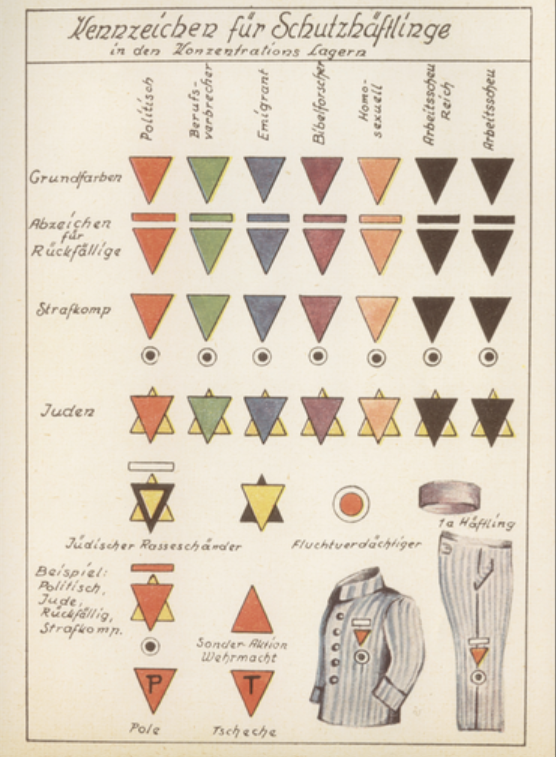

Wachsmann further describes how not just the Nazis, but also “many fellow inmates shared the social prejudices against homosexuals and ostracized them.” One gay prisoner, Otto Giering, who had been castrated by the Nazis at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside Berlin, recalled that he had been “’subjected to mockery and harassment’ by prisoners ‘of all categories’” as soon as he had been forced to wear the pink triangle marking him as gay on his uniform.

When I visited the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site outside Munich last summer, however, I was stunned to learn that anti-gay discrimination persists at the site today, long after it was liberated from the Nazis nearly 80 years ago.

When I visited Sachsenhausen back in 2006, I particularly noticed how actively attended with flowers the memorial to LGBTIQ prisoners was. I took pride that our ongoing movement for dignity and equality was visible to visitors alongside the terrible history the camp represented. As I approached Dachau, I anticipated a similar experience.

In one of the first rooms of the Dachau museum, I saw an explanation of the persecution of gay prisoners. But as I proceeded through the rest of the museum, I found nothing else—in stark contrast to exhibits and memorials about other categories of prisoners. I exited the museum, walked in the hot sun down the poplar-lined path where numerous prisoner barracks once stood, passed three large modernistic Catholic, Jewish, and Protestant memorials, and arrived at the remains of the gas chamber and crematoria, surrounded by several other smaller religious memorials.

Having still seen no queer memorial, I happened upon a very well-informed tour guide and asked her whether there was one. She seemed to welcome my question, and her lengthy response took me aback.

The guide explained that the Comité International de Dachau (CID), founded even before the liberation of the camp on April 29, 1945, claims to represent all prisoners from over 30 countries who were detained at Dachau. The CID has the power of “co-decision in all major affairs concerning the Dachau Memorial.” The guide told me that, for years, the CID prevented installation of a memorial to gay prisoners at the camp museum.

In response, the Protestant Church of Reconciliation, one of the three major religious memorials I had seen during my walk through the camp, announced that they would proudly house a pink triangle memorial because they, not the CID, controlled the content of their building. The guide herself took pride in this fact as a member of the denomination. The guide, however, also articulated the chilling irony that the pink triangle was forced to exist “in exile” within, of all things, a concentration camp.

But that was not all. The modernist “International Monument” designed by Nandor Gild, who won a CID design competition to create an artistic memorial, occupies a central position in the camp. The installation includes a striking sculptural relief depicting “a chain symboliz[ing] the solidarity between the prisoners” with modernistic depictions of variously colored triangles by which the Nazis denoted different prisoner group identities on prisoner uniforms. But missing from the sculpture, installed in 1968, are three particular triangles: the black triangle worn by so-called “anti-socials,” which included Roma, Sinti, and lesbians, among others; the green triangle for purportedly “professional criminals”; and the pink triangle for homosexual men.

The sculpture and the rest of the Monument still remain in their original form today over 55 years later with no additional sculpture added with representations of the missing black, green, and pink triangles that had been unjustly excluded from the original one. It wasn’t until 1995 that the CID, in its own words, “granted permission” for the exiled pink triangle memorial to be delivered from exile and relocated to the museum, where it is located today, although I personally did not find it.

Furthermore, the guide also told me that nowhere in the entire memorial site is an exhibition explaining the site’s own history of prejudice, ignorance, and injustice in the creation and maintenance of the memorial itself, even though the CID claims as its mission not only to preserve and present the history of Dachau but also equally importantly “not to let this happen again.”

As the guide and I reflected on how former Dachau prisoners and their descendants today who run the CID have failed to recognize the common humanity of all those who were detained or murdered at Dachau, the guide offered a somber assessment: “Being imprisoned in a concentration camp doesn’t necessarily make you a better person.”

Of course, I hope that the Dachau Memorial site will soon adequately commemorate all those who suffered there. But as I have contemplated the guide’s sobering observation for months now, I realize its importance is not confined to Dachau or to times when the human heart is blind or callous. I believe it invites all of us to examine the sources of our own empathy toward others and how, why, and when we act as “better persons.”

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

6/26 and Beyond

Published on November 7, 2024

Recent Comments